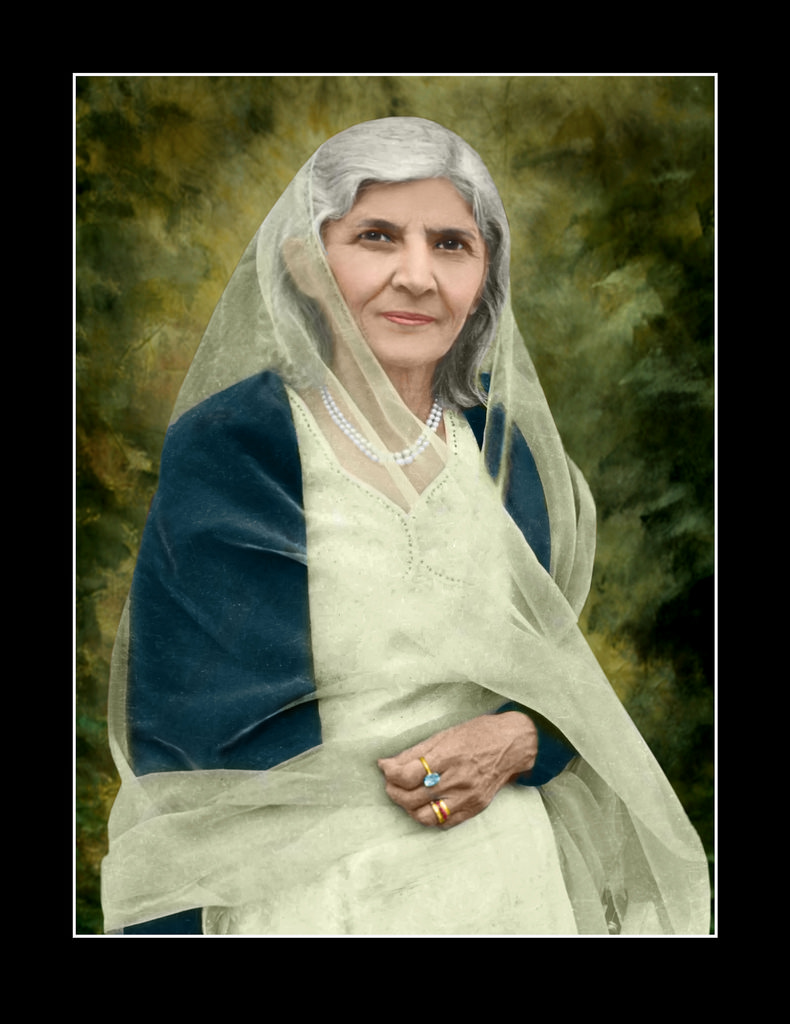

This past week, Prime Minister Imran Khan marked Women’s Day by paying tribute to Fatima Jinnah, ‘who stood steadfastly beside the Quaid in his struggle for Pakistan.’

While the mention merited praise – Ms Jinnah having long been consigned to a postage stamp in our collective memory – the prime minister fell for the same trap. The female was only an adjunct of the male, in this case, an aide to her beloved brother.

By the time we mark the next Women’s Day, that needs to change. Why this is doubly important is because Pakistan is among the worst places in the world to be a woman: it’s ranked the second-lowest in gender equality (per the World Economic Forum), first in discrimination against women (per the Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace, and Security), and the lowest in female workplace participation in South Asia (per the Global Gender Gap Index).

Throw in a raft of nightmare laws like the Hudood Ordinances and the qisas and diyat amendments, only one of which has been reformed, and you end up with a modern-day hellscape for over half the population.

None of this, of course, is to stop everyone’s uncle from telling young women that the country is fast evolving, though if this be evolution, we’ve yet to evolve beyond the common chimp.

Much of that stunted growth can be traced back to how we treated our female founder. Why we don’t hear the expression ‘female founder’ is because we’ve yet to convince ourselves. For most Pakistanis, Fatima Jinnah is the First Sister. To others, she is the Madr-e-Millat, the mother of the nation – defined yet again by her brother and (proverbial) sons.

We tend to forget that Ms Jinnah was a stateswoman, a presidential candidate, and a dental surgeon. From her admission in the Dr Ahmed Dental College in Calcutta – thought an entirely radical step for Muslim girls back then – to her bid for high office a quarter-century before Benazir Bhutto, Ms Jinnah was a trailblazer in every sense of the word. She was an extraordinary woman, at a time when extraordinary women were thought deeply dangerous. In many ways, they still are.

But to soothe the historian’s ego, Ms Jinnah’s story is supposed to end where Pakistan’s begins. With the refugees somewhat settled and her brother having passed away, we’ve long assumed Ms Jinnah’s mission in life was over. It was not.

Soon enough, Liaquat Ali Khan began a proud Pakistani tradition of feeling threatened by the ladies. Though some blame the animus between Ra’ana Liaquat and Ms Jinnah, Liaquat’s supporters soon began nudging her out of public life. Pages thought offensive to the first prime minister in Ms Jinnah’s My Brother were torn out.

And as the country’s troubles worsened after Liaquat’s assassination, Ms Jinnah, aghast over the wreck that was being made of the new Pakistan, retreated to Flagstaff House in Karachi. Many authors treat her here as a white-haired ascetic, despairing over her brother’s memory, but she had far more agency than that. “The woman is in no way inferior to the man,” she told her companion Sorayya Khurshid during the wilderness years, “but that is how our society has chosen to perceive her…before marriage, she has to obey her parents, and later she has to spend the rest of her life obeying her husband. She has to submerge her personality into his…his being male gives him the authority to be unjust to the woman.”

Ms Jinnah had no such plans. She thought Iskander Mirza ‘a time-server’, the Muslim League a shadow of its former self, and that East Pakistan was being treated the way the Raj treated its colonies. Her sympathy for Bengali leaders Suhrawardy and Mujib was no coincidence – she became one of the loudest critics of the state’s neglect towards East Pakistan. And when she could bear it no more, she entered the arena, running for the presidency at age 71.

As of 2019, Ms Jinnah’s lonely fight for democracy has been forgotten. The man she stood against, however, looms large.

There is no better icon for the patriarchy than Ayub Khan, just as there could be no better foil for Fatima Jinnah. Referred to by the British press as a ‘fine figure of a man’ – echoing what the British had said of another intellectually limited strongman, Uganda’s Idi Amin (‘not much grey matter, but a splendid chap to have about’), Ayub was the shining white knight that weak states and insecure men have long adored.

A field marshal without having won any wars, a president without popular election, an army chief by dint of an air crash that killed his superiors, Ayub embodied male entitlement. His justification for dictatorship was if one pardons the modern expression, mansplaining at its best: “We are not like the people of the temperate zones,” he said. “We are too hot-blooded and undisciplined to run an orderly parliamentary democracy.” Put simply, Pakistan was much too hot for jamhooriat.

It follows that the coverage of the presidential campaign was drenched in ‘60s sexism. The New York Times referred to Ms Jinnah as a ‘pale wraith’ and to Ayub as ‘a strong, energetic man’. Ayub was no less oblivious. “They call her the Mother of the Nation,” he whined, “then she should at least behave like a mother.” For Ayub, well-behaved women didn’t make history.

Ayub’s own behaviour was panicked. As Fatima became the lightning rod for all the discontent in the country, the field marshal brought elections forward two months ‘to break her bandwagon’. His oratory was coached by a minister called Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. Public rallies were banned. The Madr-e-Millat was dubbed a foreign agent. Full page government ads claimed “Miss Fatima Jinnah was greeted in Peshawar with the slogans of “Pukhtoonistan Zindabad.’”

Despite the usual dirty tricks, Ms Jinnah marched on. It was Ayub that was unready for democracy, she would say, not the people of Pakistan. A press report about Ms Jinnah’s supporters from 1964 sounds an awful lot like the people that created the country: ‘intellectuals, teachers, lawyers, journalists, university students, labour groups throughout the country who favour local self-government over strong central rule…and of course, women.’

By contrast, Ayub enjoyed the support of ‘the armed forces, the senior civil servants, the industrialists, the well-to-do farmers and even of many of the underprivileged.’ With the exception of the underprivileged, we now know which constituency has fared better over the years, a contrast that also marks the tragedy of this country.

Ms Jinnah lost the election amid allegations of mass rigging. She was never the same again.

Nor, for that matter, was Pakistan. First, by perpetuating military rule, its democracy suffered. Irony, however, was in great supply: when the Ayub regime began to totter, Bhutto told a crowd in Peshawar, “It is a government of cannibals. It ate up Nazimuddin and Suhrawardy—I do not want to name Madar-i-Millat – and still, it feels hungry.” Why ZAB couldn’t bring himself to say the words ‘Fatima Jinnah’ is anyone’s guess. Eventually, Mr Bhutto was cannibalized in turn.

Second, Dhaka – which gave Ms Jinnah a complete clean-sweep – would be condemned to the most brutal blood and gore just seven years later, tearing the country in two. Bengalis had dominated Ms Jinnah’s electoral alliance. It is now left for us to wonder what could have been, had they been given their say.

Third, Karachi: the Urdu-speaking community came out for Ms Jinnah in droves and, like Dhaka, Ms Jinnah swept the city. They were rewarded by a ‘victory parade’ led by Ayub’s men, in which truckloads of thugs drove into Muhajir strongholds, and beat and bludgeoned Ms Jinnah’s voters. Karachi soon erupted in ethnic rioting that saw over thirty dead. It would be the first of many.

By forgetting Fatima and forsaking the lessons of 1964, Pakistan has suffered deeply. Those lessons run the gamut of any young nation’s growth: they concern democracy and tyranny, war and peace, solidarity and ethnic violence. Over half a century since her death, those lessons require revisiting – if indeed they were visited at all.

Finally, by reassessing Ms Jinnah’s place in our history, Pakistan may come to recognize her for what she was: the most extraordinary woman of her time, above and beyond the men she fought, and the country she fought for. Pakistan will be a better place for its women when it does. And it has dire need to be.

Khan is a lawyer. He tweets @AsadRahim