In March, Punjab’s drug task force acted on an anonymous tip about a home-based medical clinic in the northeastern city of Rahimyar Khan. Its owner, a middle-aged man, was a herbalist, locals believed. His powdered concoctions were famous for curing any ailment, no matter how serious.

Many were hooked. But few knew what they were consuming. The man was mixing steroids and painkillers. When the agents finally raided his clinic, they were horrified to find a waiting room filled with men and women suffering from physical deformities. “These people had been taking his medicines for a long time,” Muhammad Sohail, Additional Secretary Drug Control, tells Geo.TV, “It had changed their appearance.” Their bodies were disproportionately bulky. Their faces swollen.

Today, the imposter is behind bars, waiting for trial. If convicted, he could face fourteen years in prison under Punjab’s revised drug legislation.

This was a small set up, in a smaller city. But fake or ill-made medicines are easily available over-the-counter at medical stores across Pakistan. A 2013 report by the World Health Organization revealed a shocking reality. Between 30 to 40 per cent of medicines sold in Pakistan are fake, it stated. Government officials, however, refute the report and claim the numbers are almost half of that, but admit that the sale of fake drugs is a dangerous problem.

100 people died, in 2012, after taking contaminated heart medicine supplied by the government-run Punjab Institute of Cardiology in Lahore. “No one was punished,” laments Ali Jan Khan, Punjab’s Secretary Primary & Secondary Health, “That company, Efroze Pharma, is still operating today. It has been blacklisted by Punjab, but I don’t know about the other provinces.”

Last year, 400 people were arrested in Punjab, the country’s most populous province, for peddling counterfeit drugs. Police raided 65,000 pharmaceutical shops and medical units and sealed some 3,500. The arrested were either operating large, unlicensed manufacturing units or were mixing chemicals over their kitchen stove.

The same year, Punjab’s chief minister Shehbaz Sharif called the trade of spurious medicines “a form of terrorism.” Soon after, his provincial government launched a series of initiatives to catch up to the crooks. It set up a helpline, to encourage the public to report illegal units. If the anonymous tip proved to be accurate, a person could take home prize money of Rs 1 million.

“We are already investigating seven cases reported on our helpline,” says Khan, “Recently, we raided six small houses in Kasur. Entire families were involved in the making of these drugs.”

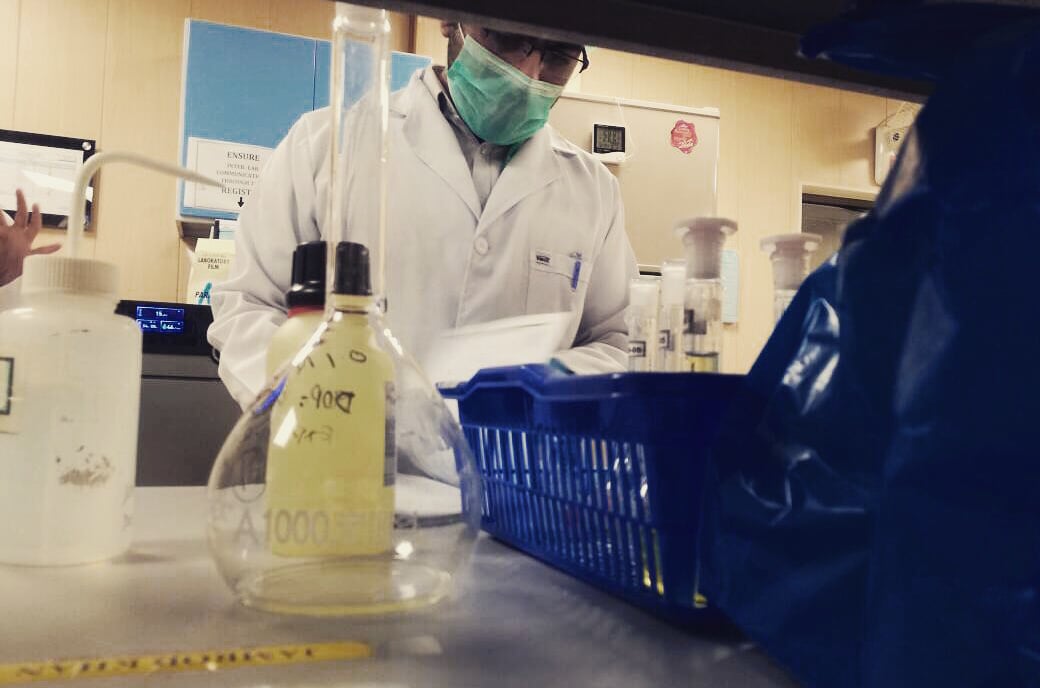

Punjab has also upgraded and revamped its five drug-testing laboratories with the help of the London Government Chemist Institute.

The laboratory in Lahore is a recently renovated building with hardwood floors and glass doors. Mohammad Sohail works here with a team of 96 chemists and lab technicians. Their job is to go through 1,000 medicine samples every month, brought in through raids and random selection.

One drug that repeatedly fails their tests is the liquid suspension of Paracetamol, an inexpensive painkiller prescribed to children to cure headaches and fever. “There are a lot of companies in Pakistan that manufacture the medicine,” Sohail tells Geo.TV, “The samples aren’t necessarily fake. Their quality is just not up to the international standards.” The other troublesome drug is Augmentin, whose fake versions are also being widely produced.

Replicas are made of medicines that are in demand or are otherwise expensive. Criminals can make a lot of money since the risk is low and the profits high. The mixtures – useless and fatal – are then sold to unaware or desperate consumers.

Viagra, a medicine for erectile dysfunction and pulmonary arterial hypertension, is unlicensed in Pakistan. Any distribution of it is illegal. Yet, there’s a burgeoning and a very profitable market, through online and under-the-counter sales, of ill-made and fake Viagra pills.

“Fake medicines is a criminal activity,” explains Dr Assai Ardakani, a representative of the World Health Organization in Pakistan, “but sub-standard medicines is a legitimate business, which is why it is a bigger problem.” Very few companies, he says, can maintain the international Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP). Hence, the medicines they produce are less effective. According to the government data, there are over 80,000 brands of 800 drugs in Pakistan. In Punjab alone, there are approximately 30,000 to 50,000 medical units or sale points. Those are big numbers, and the big numbers are a regulatory nightmare. The provincial drug agency only has 350 inspectors.

“I can’t think of any other country with as many brands. In Saudi Arabia, for example, there are only 2,000 companies,” explains Khan.

For a complete shutdown of the fake medicine supply chain, the Punjab government passed the Punjab Drugs (Amendment) Bill 2017 in February this year. The revised bill imposes stricter penalties, six months to 14 years behind bars, and higher fines for selling fake and sub-standard drugs, and life imprisonment for those caught repeating the offense.

Legitimate drug manufacturers were furious, terming it a “black law.” “The government can hang the fake manufacturers for all that we care,” says Tahir Azam, president of the Pakistan Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association, “But you cannot have the same punishment for them and legal, registered companies.”A trade union of wholesalers, distributors and medical store owners took to the streets in protest. The government didn’t respond. They shut down medical stores across the province. The government still didn’t budge.

Then, mid-afternoon on March 13, a suicide bomber struck one such protest in Lahore, killing 16 people, including six from the pharma industry. Soon after, says Azam, they heard back from officials and talks began. Even today, the negotiations are ongoing but have hit a deadlock. For the Punjab government, the new prison terms are non-negotiable. Falsifiers are murders, they insist. For Khan, it’s a matter of life and death. “These firms, these people, are playing with our lives. Why should we go easy on them?”