No Secrets...

Here is what you need to say when talking to your child about sexual abuse

May 20, 2017

It wasn’t until the mid-70s that child sexual abuse first began to be recognized as a prevalent problem by mental health and child welfare professionals. But in Pakistan, the issue had not been openly discussed until recently.

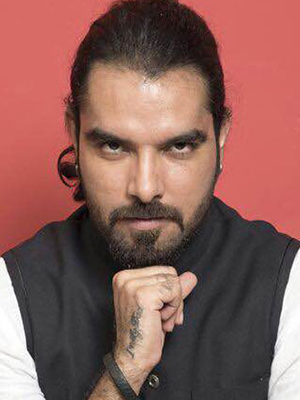

Last year, a television serial Udaari, raised the issue of child sexual abuse and was received with much controversy and threats by the Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority. Despite this, Ahsan Khan, who played the role of the sexual perpetrator received the Best Actor Lux Style Awards 2017 for his part in the serial. This recognition of the actor, and the cause, was then reduced by a “joke” made by Yasir Hussain, who called the child molester “beautiful” and wished, on stage, that he too could be a child.

Comments like Hussain’s not only normalize child sexual abuse but also minimize the importance of the issue. In 2016, the number of reported child sexual abuse cases increased by 10 per cent compared to 2015, according to Sahil, an NGO that works on issues of child sexual abuse. This figure is likely conservative given that many cases never get reported.

According to World Health Organization (WHO), child sexual abuse can be defined as “the involvement of a child in sexual activity that he or she does not fully comprehend, is unable to give informed consent to, or for which the child is not developmentally prepared and cannot give consent, or that violates the laws of social taboos of society.” The act of abuse can also be perpetrated by another child of an older age or development. Generally speaking, the legal age of consent is 18 years, however, societal norms can also influence the age at which the child is held responsible.

In majority of the sexual abuse cases, children do not immediately disclose the incident after it occurs. Despite established societal norms that stigmatize disclosure of sexual abuse, it is extremely important for parents and guardians to listen to and believe their children when such information is shared by them. Research indicates that children rarely make up stories about being sexually abused. Additionally, signs of physical trauma of sexual abuse are not always visible since physical force is seldom used. If a child gives verbal cues or shares information indicative of an incident, it’s very important that parents take those cues seriously and talk to the child.

Starting a dialogue with children when they are young, as early as even three years of age, is key in helping them identify issues and risks. Establishing a trustful relationship, sharing feelings and encouraging them to express theirs will help in identifying why a child is feeling sad or scared. As children grow up, they not only develop a curiosity about their physical world, but also about their own bodies.

Teaching children the names of their body parts is essential in identifying abuse and violation of their bodies if it occurs. Building on that, parents should also teach the difference between appropriate and inappropriate touching; these instructions should be made clearly, and in an age-appropriate language and detail. Using situational examples is important in relaying understanding. Asking, “If Uncle hugs you for too long, how would that make you feel?” “If it makes you feel bad, is that good touch or a bad touch?” “Will you come and tell me if you feel bad when he touches you?” These are some questions that parents can ask their children to establish dialogue. This type of communication needs to be a recurrent occurrence between parents and their children.

In majority of the cases, the perpetrator is known to the child, and may or may not be a family member, which can make it even harder to share an incident of abuse. Oftentimes, children don’t share such experiences because they are afraid of the perpetrator or because they believe that they have done something wrong. Young children have the ability to make a distinction between right and wrong, even if they don’t have the rationale or insight about the “why.” This puts them in a position where they may feel they are at fault, especially, if the abuser makes them think that nobody will listen to them or believe them. The abuser may also bribe or threaten to hurt them. Parents need to reiterate over and over that the abused child is never to be blamed and what he/she shares will be believed to establish trust and so that the child will turn to the parents if sexual abuse does occur. Behavioural cues can also be an indication of abuse. For example, sexual content in play, artwork or story-telling; sexual behavior on the child’s part or sudden change in behavior i.e. either becoming aggressive or withdrawn; nightmares or sleeping problems; sexual knowledge beyond a child’s level of understanding; and other behaviors indicative of stress can all be signs of child sexual abuse.

While the topic of child sexual abuse and molestation may be an uncomfortable one for parents to discuss with their children, the emotional, physical, and psychological short and long-term impact of sexual abuse surpasses any discomfort. This is a conversation parents need to start having to make children aware of boundaries, risks, and prevention.

Humayun is a practicing psychologist, educationalist, and research and policy analyst. She can be reached at [email protected]