Pakistan’s transgenders: The strangers at work

Pakistan’s transgender community is increasingly enrolling in schools and colleges, but is there really a future for them?

May 31, 2017

Alauddin Khilji, the 14th-century sultan of Delhi and the most powerful king of the Khilji dynasty, was exceedingly fond of one his generals. Malik Kafur was a strapping young man. Born a Hindu slave in Gujrat, he later converted to Islam and led a series of campaigns to expand the Khilji rule to India’s provinces south of Delhi. Kafur was fearless and for that, he was named Malik Naib, deputy ruler.

In those days, India’s most famous general and deputy sultan was a transgender person.

This was no exception. During the Mughals rule, hijras, and transgender people played an important role in the royal courts. They were political advisors, administrators, generals, and guardian of the harems. But with the onset of the colonial rule from the 18th century onwards, the Europeans criminalised eunuchs. Hence began their downfall, which set in place a prejudicial attitude that continues today in India and Pakistan.

Tucked away in the narrow and winding streets of Kala Pull, a derelict suburb in Karachi, is a small, nondescript house. Inside are three cramped rooms, with peeling paints and waterlogged walls. Shama, a 45-year-old transgender woman, is the occupant of this house. In the mornings, she roams the streets of Karachi begging for a few rupees; at night, she collects whatever is thrown her way at weddings.

Shama is alone. Her family abandoned her at a very young age. She was 10, maybe 11 when a guru took her in and trained her to dance.

“Is it my fault that I was born this way?” she asks, narrating her early life, “Am I not human?”

Although hard-pressed, today, she says she is content with whatever little she has. She has no expectation from her relatives, but she does have some from the government, who can help take her off the streets.

For Shama, her biggest disadvantage is the lack of education. But, for Sapna, another transgender woman in Karachi, that is not a shortcoming. Yet, they both lead similar lives.

30-year-old Sapna completed her F.A. a few years ago. Since then, she has been in search of a good job, but with no luck.

“I did not pursue higher education to earn money through dancing,” she tells Geo.tv, adding that “some time back, a community centre was made for our kind in the Defence area. But now, it has been shut down because the government did not pay any attention to it”.

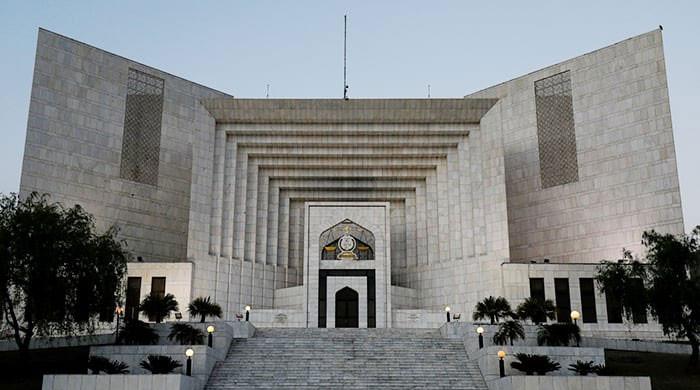

It’s a bleak trajectory, yet some things are looking up for Pakistan’s third gender. Recently, the Supreme Court of Pakistan ordered that the transgender people be included in the ongoing population census. The final count is still ongoing, but transgender activists estimate the total population to be 350,000-500,000.

In another landmark judgment, the apex court in 2012 declared eunuchs to have equal rights to that of other citizens. It further instructed the government to keep an employment quota of 2 percent for them.

Shortly after, the Sindh government hired three transgender people. Two of them were forced to leave their offices on account of sexual harassment and mockery.

In March, Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaaf (PTI) presented a bill in Punjab Assembly that asked for more stringent protection for transgender people. Punishments under the bill range from Rs. 100,000 to two years in jail for harassing a eunuch. The bill also calls on the provincial government to set up rehabilitation and community centres for the community throughout the province.

Meanwhile, in June 2016, the KP government reserved an amount of Rs. 200 million for their welfare.

In the current environment, transgender people are taking a more proactive role in the society as well. Nisha, 25, is a beacon of hope for her community. Shunned by her family, she helped herself get an education and is today studying law at a private institute in Karachi.

“I have never faced harassment on campus or otherwise,” she says, “My classmates respect me. What my people need, most of all, is an education to be able to demand their rightful place in the society.”

Hussain Javed is a researcher at Geo TV and can be contacted at [email protected]