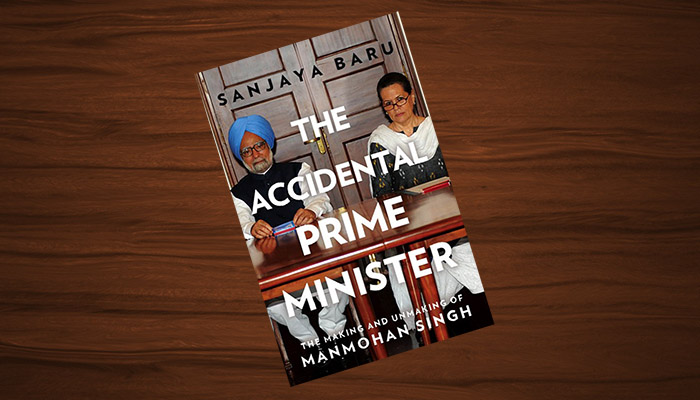

Book Review: The Accidental Prime Minister

In countries where the premier is only a symbolic leader with the real power lying elsewhere, such premiers are often referred to as 'accidental' or 'dummy' prime ministers

June 05, 2017

In a parliamentary system, the prime minister is the head of the government, at least on paper. There are countries where the premier is only a symbolic leader and the real executive power instead lies elsewhere. Such leaders are often referred to as “accidental” or “dummy” prime ministers.

Pakistan is no stranger to accidental prime ministers. In the recent past, it has had Raja Pervez Ashraf, Yousaf Raza Gilani, and Shaukat Aziz. Examples from the more distance past include, Mohammad Ali Bogra, Huseyn Suhrawardy and Malik Feroz Khan Noon.

How do these leaders operate? And how do they work under directions? Indian policy analyst Sanjaya Baru’s 2014 memoir, “The Accidental Prime Minister: The Making and Unmaking of Manmohan Singh,” provides us with some insight on powerless leaders.

Baru served as the media advisor (2004-2008) to India’s former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, who he writes landed the job accidentally. The country’s 13th premier’s rule (2004-2014) was tumultuous. His second tenure was peppered with allegations of corruption and wrongdoings. Even though the prime minister was not accused of syphoning wealth for himself, he was excoriated for looking the other way as his ministers dried up the coffers.

In his book, Baru portrays Singh as innocent, but helpless. When stories of corruption began making headlines, the prime minister chose to present himself as untainted, even if his colleagues were not. This proved fatal for his image.

It was Baru’s job, as an advisor, to present the achievements of the Indian National Congress to the media. But he was restrained by what he could and could not say. Singh had advised him to craft his party and his own image, in a manner where he does not appear more important than the president of the INC, Sonia Gandhi, and her son, Rahul. Baru writes that Singh had a self-deprecating attitude, where he was convinced that his political existence was only due to Sonia Gandhi.

Singh was cautious in every step of the way. A recent example did not give him much confidence. He could not forget how Narasimha Rao, India’s ex-prime minister was treated. Rao chooses to distance himself from Gandhi during his five-year tenure. Afterwards, when Gandhi took over Congress, she sidelined him and reduced his position in the party. When he died, Rao’s family was barred from carrying out his last rites in Delhi, even though the funerals of ex- prime ministers are, by protocol, held in the capital. This maltreatment of Rao left a deep impression on Singh. As a result, he was careful to credit Gandhi for all that went well, and took the blame for all that didn’t.

Interestingly, the author also writes that Singh earnestly wanted to resolve all matters of contentions with the then- President of Pakistan Pervez Musharraf. But Gandhi did not allow him to do so.

The book is a rare perspective on how dynastic politics in South Asia shapes and in other cases restrains leaders. It is a must read for those interested in regional politics. It is nearly impossible for an ordinary citizen to have access to the corridors of power, which is why books such as ‘The Accidental Prime Minister’ are invaluable.

Omar Javaid is a senior researcher at Geo Television