What Pakistan can learn from the UK election

There is no predicting, even for experts, even under a military dictator, which way the electoral winds will blow

June 13, 2017

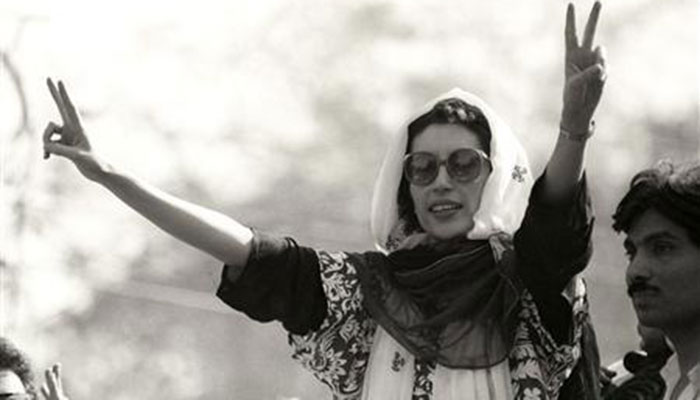

Even in the hardest of times Benazir Bhutto, former prime minister and leader of the Pakistan Peoples Party, strongly believed in elections as a catalyst for change.

In 1984, the Movement for the Restoration of Democracy held a crucial meeting in Abbottabad, at the residence of Air Marshal Asghar Khan. That night the agenda was simple: whether to participate or boycott the 1985 elections, to be held under military dictator Gen Ziaul Haq.

In those days Bhutto, aka Bibi, was living in exile in London. Bhutto had learned through her sources that Gen Zia was keen to see the movement sit out of the upcoming polls. Wasting no time, she hurriedly tried to contact Ghulam Mustafa Jatoi, the acting leader of the PPP, to instruct him not to support the boycott.

Bibi then called me and asked me to convey her decision, but even my attempts to get through to Jatoi failed. Perhaps the Pakistan Telecommunication Department was also working against us. Regardless of the outcome, Bibi favoured electoral participation due to their unpredictability.

There is no predicting, even for experts, even under a military dictator, which way the electoral winds will blow.

This memory came to mind last year after the Brexit referendum called by Britain’s Prime Minister David Cameron. The forecast was that Britain would vote ‘Yes’ to remain in the European Union. But as the tallies began to pour in, it was clear the result was a big, resounding ‘No’.

As a consequence, Cameron was forced to resign, and give way to his successor and colleague, Theresa May. May’s first day in office was overshadowed by her attempts to manage Britain’s transition from a member of the EU to an independent state.

Then came the second shocker. A confident May, who was 20-points ahead of rival Jeremy Corbyn according to several polls, announced snap elections. The British prime minister was looking to shore up her support and mandate to deal with the EU community.

Corbyn, leader of the Labour party, represented the trade unions and the politics of left. Going into the early polls, even his own party leaders doubted his chances of success.

But the pollsters were wrong. And May, who wanted to be remembered as the Iron Lady Margaret Thatcher, was wrong. She never got the mandate she had sought, leaving her party confused and scattered in the cold.

Corybn, 66, a non-starter, carried the day with the power of the people delivering a message of hope. And the people responded in kind.

Corybn’s phenomenal delivery has put Labour six points ahead of the Tories in the popularity graph a day after the polls. His manifesto to end tuition fees was a brilliant move to attract young voters; his promise of cheaper housing for the shelterless and to save the National Health Service from the capitalist scavengers appealed to all ages.

The tirade of the rightist media against the Labour leader could not hold him down, even with the surge of terrorist incidents in the country. Corybn’s rise is an astounding turnaround of the left in the face of the march of the right.

With a nearly 1.5 million Pakistani diaspora in Britain and 12 Pakistani-origin members in the new parliament, our hopes are high. The United Kingdom, it seems, won’t be electing any Donald Trumps to office anytime soon. But then again, elections are unpredictable.

Hasan is the former High Commissioner of Pakistan to the UK and a veteran journalist

Note: The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Geo News, The News or the Jang Group