A new ASWJ-linked charity in Karachi?

Pakistan formally banned the ASWJ in February 2012, due to suspected links with terrorists

July 21, 2017

It is no secret that month of Ramazan is an important and particularly hectic time for banned organisations in Pakistan. During Ramazan, militant outfits, in various disguises, go into overdrive collecting funds. Take the Ahle Sunnat wal Jamaat (ASWJ), a proscribed sectarian organisation, which was at its most visible in June, collecting donations, arranging large iftar gatherings, distributing Eid gifts and setting up a new charitable wing in Karachi, the al-Nujoom Welfare Foundation.

Pakistan formally banned the ASWJ in February 2012, due to suspected links with terrorists. Yet, every Ramazan, their activities receive a positive response especially from Karachi's well-heeled areas, they say. "We rely solely on private donations to operate," explains a member of the group, who asked not to be named, "There are people, wealthy individuals, who believe we are the right organisation for their Zakat, because we do not have any political agenda."

The success in soliciting funds may be due to the ASWJ's ability to fundraise through its charitable trusts. This is not a new strategy. Over the years, the organisation has shape-shifted several times to keep operations afloat.

Its origins can be traced back to the Sipah-e-Sahaba Pakistan, a sectarian terror group of the 1980s. After being outlawed in 2002, the SSP renamed itself the Millat-e-Islamia Pakistan. It was later rechristened as the ASWJ. (Authorities suspect that the Ahle Sunnat wal Jamaat still maintains links with sectarian militants. The organisation denies all such charges.)

After the recent crackdown on crime and terrorism in Karachi by a paramilitary force many banned organisations have either gone underground or been routed out. But the ASWJ has remained in plain sight and now, it seems, has a new wing, the al-Nujoom Welfare Foundation.

But the Foundation rubbishes any association. "We have no links with the ASWJ and its members," a spokesman for the trust tells Geo.tv.

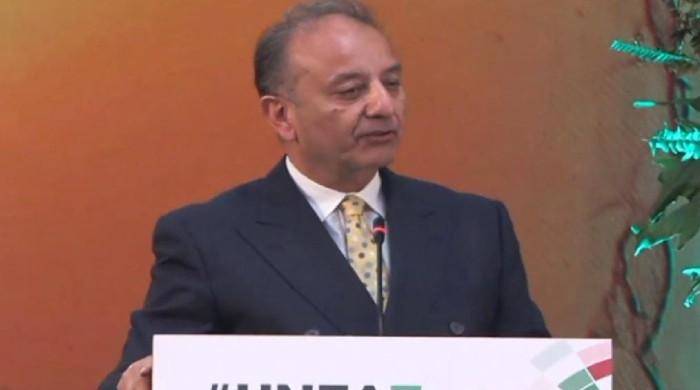

Yet, leaders of the banned outfit, such as Maulana Aurangzeb Farooqi are regulars at its fundraising events. Interestingly, Taj Muhammad Hanafi, the ASWJ's secretary general, also holds a position on the charity's board.

Since its launch, the Foundation has been particularly active advertising itself on the social media and at local mosques in the city's Landhi, SITE, Nagan Chorangi and Orangi Town. It plans to further expand by rolling out an ambulance service, building a morgue and funeral support services.

"Most of the donors give money to charities they know very little about. It is a big challenge. The fact that such organisations still operate in the city points to the failure of the anti-terrorism laws," Abubakkar Yousafzai, a development expert with the Sustainable Peace and Development Organisation, which runs a campaign for ‘Safe Charity Practices,' tells Geo.tv.

The Foundation has not raised any eyebrows in the law enforcement circles. When asked, a senior police official in Karachi admitted he knew nothing about the new charity. "The ASWJ is a proscribed organisation, legally," he said, "but it still arranges rallies in the country and takes part in elections. We do not have any clear policy from the federal government on how to deal with them."

Last year, Maulana Masoor Nawaz Jhangvi won the by elections in a city of the Punjab province. Even though Jhangvi contested as an independent candidate, the ASWJ openly campaigned for him. Active members of the outfit have also been running a labour committee in Karachi, since the last two years, that resolves workers' issues in the Landhi area.

"For the ASWJ to form a charity wing at this point will only make it more acceptable and strengthen it socio-politically," says Ayesha Siddiqa, a social scientist and author, "It is already asserting influence with labour unions. By forming a welfare wing it will further broaden its social-base."