What the body rejects

Uzma Aslam Khan writes on how Pakistan treats one of its most vulnerable populations: those with physical disabilities

August 14, 2017

Though the fall of yet another elected prime minister is tempting to write on, I will leave it to the news to cover those that make the most noise. My focus on Pakistan’s seventieth birthday is on what is not being said enough in the news: how the country treats one of its most vulnerable populations, those with a physical disability.

Not long ago, a close relative relayed to me the story of a young woman, let’s call her Naiza, who had polio as a child. Now in her thirties, Naiza has a perceptible limp, because of which, when the relative spoke of her, she called her a “bichari,” a pitiful thing.

In those days, I too had a limp, caused by multiple injuries. To be clear, I do not presume to compare the degree to which this altered my life with that of a person who has endured a life-altering illness from childhood. But for a period of many years, I had a taste of what it is to be marginalized for being on the wrong side of simple activities, such as finding myself at the bottom of a staircase; hobbling behind my friends; difficulty getting dressed; unrelenting exhaustion from having to think too much simply to get through the day. Worse than the over-thinking and even the physical pain was having to ask for help. That position of dependence was more painful than the one every woman experiences in a male dominated society, or every brown person experiences in the West. Suffice it to say that ableism –prejudice against people with disabilities – damaged me more than sexism, racism, and Islamophobia combined.

So when my relative referred to Naiza as a “bichari” because of her polio-inflicted gait, and then went on to call Naiza’s brothers “too selfish to take her in,” I seethed. Why had Naiza not been given access to ways through which to help herself, so that she might live in dignity, instead of in majboori – in helplessness?

The question applies to all people living with disabilities (or “PWDs”) in Pakistan. There doesn’t even exist data on how many this includes. The last census that included the disabled was in 1998, with the figure put at 3,286,630, or roughly 2.4 percent of the population then, a number that was contested. In 2011, the World Health Organisation put the figure at 7 percent, but this too was a rough estimate.

As Nadir Khan, a disability rights activist from Multan who also survived polio as a child puts it, “When the government does not have accurate statistics about persons with disabilities, how can it empower us?” He estimates that there are currently 2.5 million PWDs in southern Punjab alone, with the majority confined to their homes, where family members alone bear the financial and emotional cost of caregiving.

He adds that the ongoing War on Terror has left a large number of people permanently disabled, thus ensuring that the unrecorded number will keep rising.

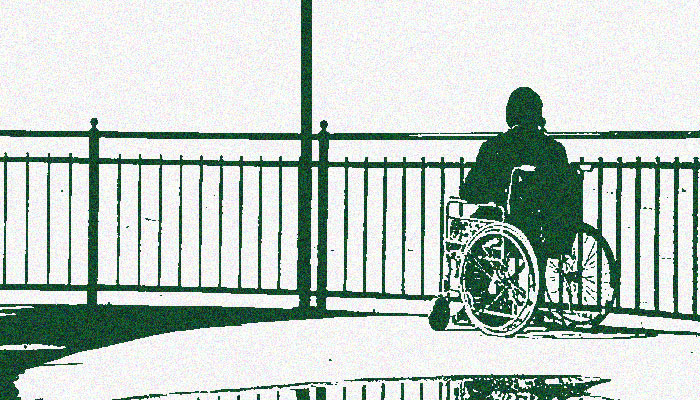

In March of this year, Muniba Mazari, an artist and Ambassador for UN women Pakistan who suffered a spinal cord injury in a car accident that left her wheelchair-bound, chose to actively reject the invisibility of her body to the state. She filed a petition in the Islamabad High Court to ask that the judiciary direct the government to collect information related to the number, cause, and severity of disability of each Pakistani, for the purpose of this year’s census. Her struggle is indicative not only of an institutional bias, but of the social and cultural one complementing it: that stigma of “bichari.”

Mazari has been outspoken about how, after her accident ten years ago, women told her mother, “A husband would never keep a wheelchair-bound wife. Poor girl, she’ll get divorced…”. Today, she cautions, “Before you ‘dis’ our ability, always remember that a person who is differently abled only needs your empathy, not your sympathy!”

Her words are worth commemorating on independence day, for they are emblematic of a change that has to occur at a structural and individual level with regards to all those whose difference puts them in a position of grave and humiliating dependence on “charity,” instead of empowerment based on rights, in a land once meant to be, equally, for its every citizen.

Uzma Aslam Khan is an award-winning writer. Her four novels include Trespassing, The Geometry of God, and, most recently, Thinner than Skin.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Geo News or the Jang Group.