After Trump, now Brics

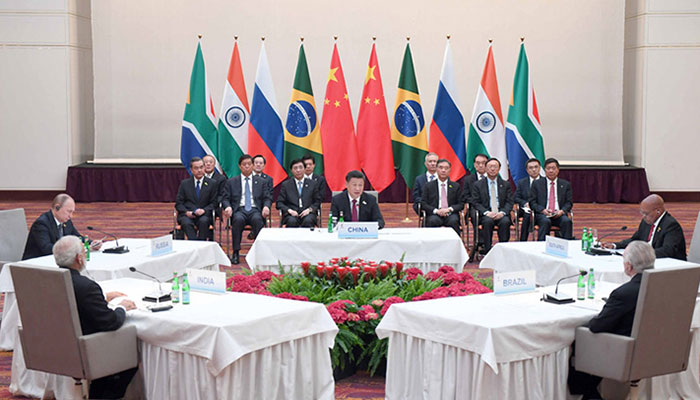

BRICS leaders' meeting in China this week. Photo: File

As the country’s top ambassadors meet in Islamabad to contemplate Pakistan’s response to President Trump’s recently announced...

September 07, 2017

As the country’s top ambassadors meet in Islamabad to contemplate Pakistan’s response to President Trump’s recently announced policy on Afghanistan and South Asia, Pakistan’s diplomatic isolation seems almost complete with the naming of UN-designated terrorists which operated from Pakistani soil for the first time in the Xiamen Declaration of the 9th Brics Summit in China.

Where will the envoys draw the line this time compared to the last time they had met for such a consultation and had recommended certain policy inputs that they thought would help them sell a revised and consistent foreign policy the world would be, at least, ready to listen to?

Brics – a forum of the fast-growing developing economies of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa – has expressed its “concern on the security situation in the region and the violence caused by the Taliban, ISIL/DAISH, Al-Qaeda and its affiliates including [the] Eastern Turkistan Islamic Movement, Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, the Haqqani network, Lashkar-e-Tayyaba, Jaish-e-Mohammed, TTP and Hizbul-Tahrir”.

With this declaration, Islamabad could stand isolated globally on the issues of ‘cross-border terrorism’ that Pakistan has now, at least at the policy level, pledged to curb and has also decided to not to let its territory be used for terrorism against other countries since the unanimous passage of the National Action Plan. But let’s not forget that the ‘leakage’ of the quite known views expressed by former foreign secretary Aizaz Chaudhry in the National Security Committee of the cabinet is also said to have contributed to the ouster of the Nawaz Sharif government.

For India, this declaration is a big diplomatic achievement since its efforts to get Pakistan-based banned (and renamed) LeT and JeM included in Brics’ Goa Declaration was frustrated by China last year. Much earlier, the UN Security Council had designated JeM and LeT as terrorist organisations in 2001 and 2005, respectively. It is indeed good to recall that the same terrorist groups were also mentioned in the Amritsar Declaration of the 6th Ministerial Heart of Asia Conference on Afghanistan in December 2016; the declaration was endorsed by Pakistan and China as well.

However, Islamabad continued to take solace in blaming both Afghanistan and India for allowing and using Afghan soil for a proxy war against Pakistan. Indeed, both Islamabad and Rawalpindi were right in their allegations against both the aforementioned countries with regard to backing the TTP and other renegade terrorist groups for terrorism across Pakistan, but the Pakistani state could not absolve itself of not being equally tough with the ‘good Taliban’. But somehow, despite an apparent shift in policy – as repeated by both successive civil and military leaderships – to not to differentiate between ‘good and bad’ Taliban and not to let any terrorist groups use Pak territory for terrorism against any other country, we continued to take flak from international community on the footprints of these groups being seen to be behind various acts of terrorism.

These groups continue to exist under various pseudonyms and the camouflage of ‘welfare’. Amid a treacherous metamorphosis, they are now becoming the bulwark of fascism at the cost of the civil society, and are sanctified as the guardians of our ‘ideological frontiers’. In a delayed, flawed and self-serving ‘de-radicalisation’ process, they are defining the national narrative on a broad range of policy issues, including jihad, Islamisation (in reality, sectarianism), foreign relations and internal and external security policies. In fact, more than challenging India and checking its brutal suppression of the Kashmiri struggle, such groups pose a much greater threat to Pakistan’s internal security and inter-faith harmony.

The change in the Chinese position on Pakistan-based militant outfits has come after India and China came to an agreement over a 73-day military faceoff on the unsettled Dokalam area close to the Sikkim sector claimed both by China and Bhutan; the latter is now not very inclined to lay claim on the territory and is expected to mend fences with China to, perhaps, keep equi-distance from the two joint neighbours. Indian Prime Minister Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping were to meet at the sidelines of the Brics Summit for what Indians described as “forward looking” discourse to put Sino-Indian relations on the “right track”, according to the Chinese side. The Brics Summit was in fact on ‘emerging markets and developing countries dialogue’ for their greater role in the global market, but it was taken over by the crisis created by the test of a hydrogen bomb by North Korea, something that can make Beijing-Washington relations reach a very tenuous situation.

President Trump’s sabre-rattling apart, Brics has come firmly against tougher sanctions or retaliation against North Korea and has, instead, asked for direct dialogue with Pyongyang. For Beijing, the Korean Peninsula’s security is more important than the Indo-Pak conflict. Moreover, they are no more enthusiastic to compensate for our extended security agendas or conflicts with our neighbours. They want us to focus on CPEC and engage with neighbours the way they are doing with India; the Sino-Indian model of economic cooperation is presented as a blueprint for negotiating border disputes.

For Pakistan, Kashmir remains a principal issue and we have learnt that the Kashmiri democratic struggle no more requires ‘guest fighters’ who now bring a bad name to their genuine aspirations. Jihadis for Kashmir are a liability and counter-productive. They are, rather, a threat to the safety and cohesion of our civil society. Pakistan can never sell its narrative to the world and will remain in jeopardy with the Haqqanis or LeT or JeM in its closet in any way.

On Afghanistan, Brics has very strongly expressed its desire for an end to the conflict and asked for a political resolution of the unending conflict through available mechanisms, including bilateral, trilateral, quadrilateral, multilateral and also Moscow and Istanbul initiatives. We must respond to the American overtures and Afghan President Ghani’s speech on this Eid offering “comprehensive political talks” since in his view “peace with Pakistan in our national interest”.

It is also in Pakistan’s national interest to have cordial relations with Afghanistan. We have lost so much for our Afghan policy for far too long, including all those ‘friends’ that we had helped too long. It is a no-win policy and must be drastically changed in favour of an Afghanistan that ensures peace within and at its borders with us.

To Pakistan’s relief, Brics has also included the TTP in its list of terrorists; that provides a ground for a quid pro quo. For that, we will have to revisit our Afghan policy and attitude towards the Haqqani Network. Indeed, it is not our job to sort out the Afghan Taliban or the Haqqanis, but we cannot also provide them any relief by endangering our own country at the same time. As they now claim to have captured more than 40 percent of Afghan territory, they must find their own way.

If at all our facilitation is required for a political reconciliation in Afghanistan, we should be willing to do our bit – however limited or effective it might be. Our national interest is in keeping our north-western and eastern borders secure and not letting proxy wars destabilise us. Why doesn’t Pakistan follow the advice of the Chinese president to have peaceful neighbourly relations with all neighbours and let all the countries of the region join hands against terrorism and against any support to any terrorist group against one another? It is time the Foreign Office told the power players to get over the hangover of Gen Zia’s destructive policies, which Pakistan can least afford now.

The writer is a senior journalist.

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @ImtiazAlamSAFMA

This article was originally published in The News

Originally published in The News