The stateless and persecuted Rohingya

Myanmar's government, led by Nobel peace prize laureate Aung San Suu Kyi, has rejected allegations of atrocities against the Rohingya, accusing the international media, NGOs and the UN of...

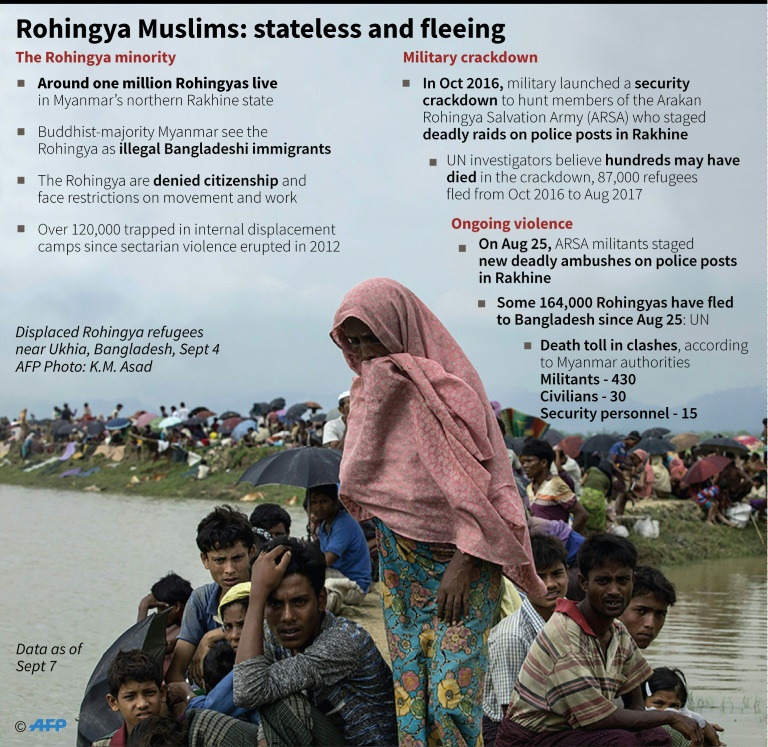

Rohingya Muslims are once more fleeing in droves towards Bangladesh, trying to escape the latest surge in violence in Rakhine of Myanmar.

This is the latest chapter in the grim recent history of the Rohingya, a people of about one million reviled in Myanmar as illegal immigrants and denied citizenship.

Stateless, persecuted and fleeing

The Rohingya are the world’s largest stateless community and of one of its most persecuted minorities.

Using a dialect similar to that spoken in Chittagong in southeast Bangladesh, the Muslims are loathed by many in majority-Buddhist Myanmar who see them as illegal immigrants and call them "Bengali" -- even though many have lived in Myanmar for generations.

They are not officially recognised as an ethnic group, partly due to a 1982 law stipulating that minorities must prove they lived in Myanmar prior to 1823 -- before the first Anglo-Burmese war -- to obtain nationality.

Most live in the impoverished western state of Rakhine but are denied citizenship and harassed by restrictions on movement and work.

Military crackdown

Despite decades of persecution, the Rohingya largely eschewed violence. But in October 2016 a small and previously unknown militant group -- the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) -- staged a series of well coordinated and deadly attacks on security forces.

Myanmar’s military responded with a massive security crackdown.

The UN believes the army’s response may amount to ethnic cleansing, but Myanmar's government, led by Nobel peace prize laureate Aung San Suu Kyi, has rejected allegations of atrocities, accusing the international media, NGOs and the UN of fabrications.

It has placed the blame for the violence squarely on the militants, saying they are setting fire to their own homes.

Fleeing to Bangladesh

According to the United Nations, more than a quarter of a million mostly Rohingya refugees have entered Bangladesh since fresh violence erupted in Myanmar last October.

In the last two weeks alone 164,000 mostly Rohingya civilians have fled to Bangladesh, overwhelming refugee camps that were already bursting at the seams and triggering warnings of a humanitarian crisis.

Scores more have died trying to flee the fighting in Myanmar's Rakhine state, where witnesses say entire villages have been burned to the ground since Rohingya militants launched a series of coordinated attacks on August 25, prompting a military-led crackdown.

Police in Bangladesh say they have recovered the bodies of 17 people, many of them children, who drowned when at least three boats packed with Rohingya refugees sank at the mouth of the Naf river that runs along the border.

Bangladesh border guards say desperate Rohingya are attempting to cross the river using small fishing trawlers that are dangerously overcrowded.

At least five have capsized leaving more than 60 people dead, police and border guards say.

Rohingya refugee Tayeba Khatun said she and her family had waited four days for a place on a boat to take them to Bangladesh after fleeing her township in Rakhine.

"People were squeezing into whatever space they could find on the rickety boats. I saw two of those boats sink," she told AFP.

"Most managed to swim ashore but the children were missing."

'Starving to death'

Those flocking into Bangladesh have brought with them harrowing testimony of murder, rape and widespread arson by Myanmar's army.

Most have walked for days to reach Bangladesh and the United Nations says many are sick, exhausted and in desperate need of shelter, food and water.

Existing camps which hosted around 400,000 refugees before the latest influx are now completely overwhelmed, leaving tens of thousands of new arrivals with nowhere to shelter from the monsoon rains.

Mazor Mustafa, a Bangladeshi businessman handing out food and rehydration fluids, said the situation was getting worse as more people arrived.

"It is not at all enough food," he told AFP of the ration kits being distributed.

"These people are hungry, starving to death together."

The latest figures mean that nearly a quarter of Myanmar's 1.1 million Rohingya Muslims have fled since fighting first broke out last October.

Bullet wounds

The recent fighting is the fiercest in Rakhine, Myanmar's poorest state, in years.

Cattle rancher Mohammad Shaker, 27, crossed into Bangladesh suffering a gunshot wound to his chest that he said was inflicted by Myanmar soldiers.

"I tried to flee with our stock near the river when the military started shooting at us," he told AFP, nursing his untreated wound.

"I fell on the ground and later my relatives found me. We hid in the hills for days, and this morning managed to come here."

Scores of refugees have arrived in Bangladesh needing treatment for serious bullet wounds, while others have lost limbs after apparently setting off landmines along the border.

On September 7, 2017, a mass funeral was held at a mosque near the border for five men whose relatives said they had been shot dead by the Myanmar military. The relatives carried their bodies over the border so they could be buried in Bangladesh.

Myanmar's army has previously said around 430 people had been killed in the fighting, including militants and soldiers.