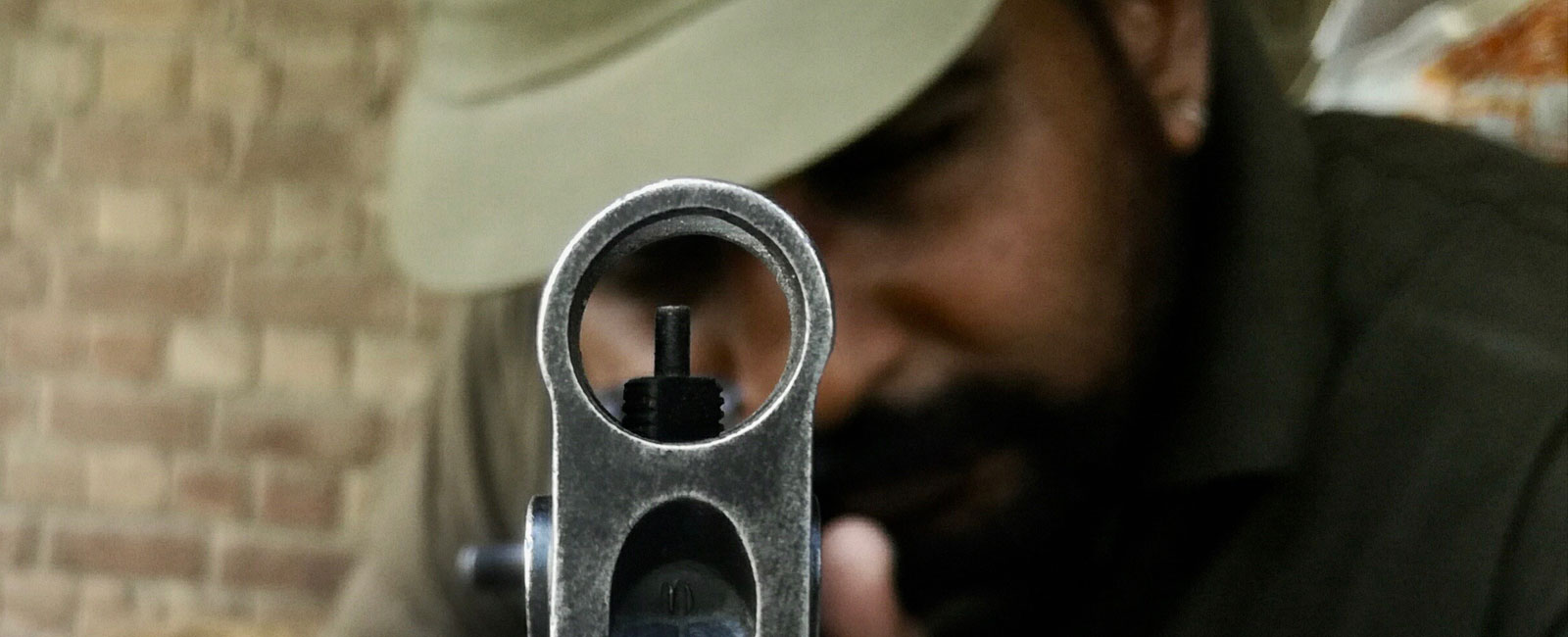

Is Lahore's police force under attack?

According to data from the Lahore police, 25 officers have died this year in terror-related incidents, while 291 have been killed in the last five years

On July 24, at half past three in the afternoon, there was a sudden change in Punjab Chief Minister Shehbaz Sharif’s plan. He was scheduled to drive past Lahore’s Technology Park to inspect the demolition of unlawfully constructed buildings. But the visit was cancelled, after a morning meeting went into overtime.

At the other end of Lahore, a young man lying in wait revved up his motorcycle, embraced his two escorts and set off, driving aimlessly up and down Ferozpur Road, a key thoroughfare in Lahore. By 3:55 p.m. he had in his sights a new target – a group of police officers lazily manning a picket. The man drove straight towards them. His explosive-laden vest sent a loud, thundering growl thorough the city of 11 million. Over 20 people were killed that day, plus nine officers of the Lahore police.

Five months earlier, in February, a suicide bomber weaved through a rally of protesting pharmacists, outside the well-guarded building of the Punjab assembly, and walked right up to the DIG Traffic Ahmed Mobin. 13 people died in the blast, including Mobin and another senior police officer. In April, a suicide attacker targeted a census team. Then, in August, a bomb exploded in a parked fruit truck, days before Pakistan’s former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif was to arrive in the city.

Four deadly attacks in just eight months this year. Fear was slowly taking hold in Lahore, a city that had until now remained relatively safe from the menace of terrorism, even as the rest of Pakistan battled against militancy.

Lahore, Punjab’s capital and home to the ruling-political party Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz, seemed to be under attack, witnessing the kind of assaults it hadn’t experienced since 2010. And in this new wave of terrorism, its 26,000-strong police force was an easy target.

“When the terrorists can’t find anyone else they come after us,” says Dr. Haider Ashraf, the DIG (Operations) of Lahore, “Because we are exposed. We are everywhere, at every protest, at every rally, outside every building.” The spate of attacks has left the police feeling increasingly under siege. According to Lahore police data, 25 officers of the force have died this year in terror-related incidents. While 291 officers have been killed in the last five years. “By targeting us [the terrorists] want to send the impression that if the police cannot protect itself, how will it protect the city?”

There may be another reason for why the police are now in the militant’s immediate crosshairs. Recently, the city police was pushed to the forefront of Pakistan’s war on terror.

When on February 22 the military launched Operation Radd-ul-Fasaad, Punjab received a special mention. Long deemed to be a crucible of dangerous militants and home to extremist seminaries, it had remained untouched by counter-terrorism operations, due to the Punjab government’s stubborn denial of terrorist footprints. Punjab’s law minister, Rana Sanaullah, has often claimed that there were “no terrorists havens” in the province. That claim has now been disabused with Radd-ul-Fasaad.

Under the Operation, the police and the paramilitary forces conduct near daily raids in the city, which has forced them to admit that there are three terrorist groups rooted in Lahore: the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan, its breakaway faction the Jamaat-ul-Ahrar, and Daesh, a Middle-East-based terror outfit.

“Daesh is still not organised here,” an official of the Counter Terrorism Department, tells Geo.tv, on condition of anonymity, “There are some radicalised individuals in colleges and schools but they do not have the capacity to conduct big attacks.”

In May, an engineering professor at a well-known university in Lahore, and his niece were arrested due to suspected links with Daesh. According to a media report, they had planned to use explosive-fitted drones to mount targets. A month later, Noreen Leghari, a medical student, was recovered from a house in Lahore. Leghari admitted to being recruited by Daesh as a potential suicide bomber. “The terrorist group is trying to establish a foothold through students, especially those studying Information Technology,” says Ashraf, “They had influenced some professors in Lahore too.”

As for the Pakistani Taliban and the Jamaat-ul-Ahrar, counter-terror operations against both are ongoing. After the bombing outside the Punjab assembly, CTD officials insist, Ahrar has been neutralised and its hideouts detected, which will prevent it from carrying out any new attacks.

Officials are optimistic about Lahore, and Punjab as a whole, being safer than other parts of Pakistan, such as the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, which witnessed over seven major attacks this year. According to police data, in 2016, there were 900 bomb threats in Lahore, but only three materialized. This year, till now, the intelligence agencies have received 177 threats, of which four were carried out. That, say police officers, demonstrates the success of the Lahore police and the intelligence agencies.

But even with improved intelligence and forewarnings, men in uniform are still dying. When in May 2015, the Zimbabwe cricket team came on tour to Lahore, “We were told that there is a 100 percent chance of an attack,” says Ashraf. Yet, rather than cancelling the match, over 6,000 security personnel were deployed around the city. In an attempt to enter the stadium, the suicide bomber killed one police officer and one civilian.

Besides cadets, political leaders and “schools, especially English medium schools in Lahore, are also targets for terrorists,” Lt Col (r) Sardar Ayub Khan Gadhi, Punjab’s Minister for Anti Terrorism, tells Geo.tv.

While on the one hand the Lahore police are battling terrorism, on the other they are battling against a bad reputation.

Officers are often accused of false arrests, graft and staged “encounters.” And the recent counter terrorism operation has only added to that perception.

After the Punjab assembly bombing, the police force went after the Afghan refugees – the “outsiders” living in the city. Poor, slum-dwelling Afghans have complained of abuse, harassment and violence by law enforcement agencies.

In private conversations, authorities accuse Punjab’s estimated 150,000 Afghan population for collaborating with the terrorists.

“Some of these people [refugees] have connections with militants,” insists Gadhi, “Till now we have not found a single facilitator who was a Punjabi. Both the suicide bombers, identified this year, were from Afghanistan.”

Pakistan’s chapter of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees says this outlook stereotypes a entire community living legally in the province.

“Not one Afghan refugee, with a proof of registration card, has been found involved in terrorism. The Ministry of States and Frontier Regions has confirmed this,” Kaiser Khan Afridi, the spokesperson of UNCHR Pakistan, tells Geo.tv.

“These refugees left Afghanistan to escape violence. They are victims too.”

Ashraf admits that it has not been easy for the force to juggle new responsibilities and the Lahore police have been learning on the job. “We were trained to tackle crime, not terrorism, but we must take on the new role to keep the city safe.”