The Good, the Bad and the Unusual of Census 2017

The 2017 census results are contrary to circumstantial evidence. Many are sceptical of the results and the process. Since 1998, Karachi has become denser but not according to the population census

The provisional results of the population census 2017 are unusual and alarming. In the ensuing months, since the report was made public, the results have earned the ire of two major political parties of Sindh—the Pakistan People’s Party and the Muttahida Qaumi Movement-Pakistan. The latter claims that the data under-counted Karachi by over 10 million people.

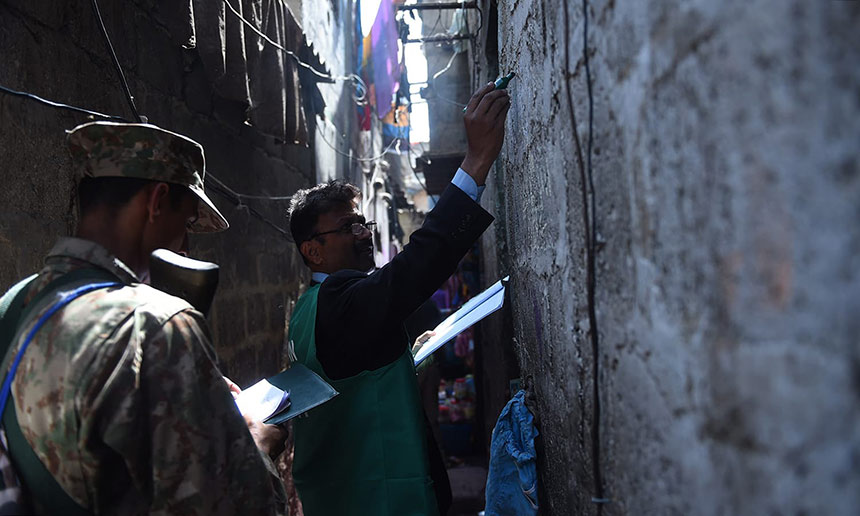

Many are sceptical of the results and the process, which was initiated on March 15 by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics.

The summary, as released by the PBS last month, pitched Pakistan’s total population at 207 million, with a national growth rate of 2.4 percent.

As per the results, Pakistan is now 36.38 percent urban. But here is the problem. The definitions of rural and urban are vague, to say the least.

Then there is the case of Karachi, Pakistan’s largest city in terms of population, which stands out from the provisional summary.

Earlier, between the two census periods of 1981 and 1998 Karachi division’s annual growth rate was reported to be 3.56 percent. However, between 1998 and 2017 it seems to have plunged to 2.6 percent.

In 2017, Karachi’s total population stands at 16.05 million. This means that a total of 6.19 million people have been added to the city’s population since 1998.

The intercensal growth of Karachi in 17 years (1981-1998) was 81.25 percent. Now, after a gap of nineteen years (1998 – 2017) the intercensal growth has fallen to 60 percent.

In other words, in 17 years Karachi added 4.4 million to its base population but in 19 years it only added 6.19 million people?

Korangi, a large area in Karachi, was formerly a part of District East. Then in 2013, it was divided and designated as a district in itself, thus distributing Karachi into six administrative districts: Central, East, West, South, Malir and Korangi.

In 1998, Karachi’s District Central was the most populous district with a population of 2.27 million and with a percentage share of 23.11 percent, followed by District West with a population of 2.08 million and a percentage share of 21.2 percent. In 1998, both districts, cumulatively, housed 43.5 percent of the total population of the city.

As shown in Figure Two, the results of the 2017 census are, if not strange, unusual when it comes to the Per Annum Growth Rate (PAGR) of various districts of the Karachi Division.

In contrast with the 1998 reported PAGR of 3.09 percent, a less palpable and palatable PAGR of 1.41 percent for District Central is cited in the provisional results of census 2017. Same holds true for District West, where the PAGR has dropped down from 5.04 percent in 1998 to 3.35 percent in 2017. The question that needs to be asked is what are the reasons for the fall in Per Annum Growth Rate: successful family planning programs, mass exodus or unusual deaths? Rather, it seems that the quoted figures are contrary to the circumstantial evidences.

On-site observations, background discussions and the national events pose a challenge to the reported figures about Karachi. Beside natural growth, Karachi is a great host to the perennial migrants from up north, which has been a historical phenomenon. The reasons for migration vary from trying to gain economic freedom, to avoid persecution or to escape the wrath of nature. The strings of military operations in FATA, floods in 2010 and 2012 in parts of Pakistan, are just some reason that might have pushed people to rush to Karachi. As per the 1998 population count, the District Malir and West cumulatively accommodated 55 percent of the migrant population. Sindhi and Pashto are the dominant languages of Malir, while Urdu and Pashto were the dominant languages of District West.

Going by the new figures, the District Central’s per annum growth rate has declined and only 693,695 persons were added between 1998 and 2017. However, a travel along the main arteries and corridors of District Central tells an altogether different story. During the same period a considerable densification of the district has taken place. Multi-storeyed flats are now a common visual which was a relatively rare phenomenon in 1998. There has also been an exponential price hike in real estate prices. A double storey 240 square yards house that used to cost Rs. 3 million in 1998, is worth Rs. 28 million in 2017: an increase of 833 percent. The land has become so valuable that the newly evolved army of developers, in the District, have abandoned the idea of boundary walls and open spaces.

On ground realities tell a different story than that on paper.

In 2010, the media reported that 75 percent of the 3.35 million illegal migrants in Pakistan live in Karachi. If we just go by that estimate, then that means that least 2.5 million migrants are missing from the 2017 headcount.

Locating the missing elements and plugging loopholes is important for a fair allocation of resources.

There is another interesting trend that can be traced out in the new report regarding Karachi: the narrowing down of the gender gap.

This will call for a major readjustment in public policy and social programs by the respective provincial and local governments.

Human beings irrespective of caste, class, creed, gender and ethnicity need to be counted for the sake of fair planning and subsequent allocation of resources. Accuracy, and the acceptance of the population census by major stakeholders, is pivotal for the credibility of the exercise.

Mansoor Raza is a freelance researcher and a peripatetic with a special interest in demographic and societal changes in Pakistan. He can be reached at [email protected].

Note: The views expressed in the article are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Geo News or the Jang Group.