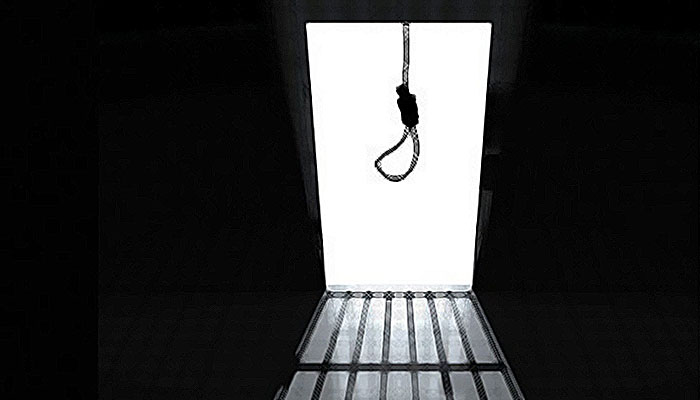

A Pakistani woman on death row

No court of law, no quality of healthcare, and no amount of commiseration can ever compensate Kanizan Bibi

October 10, 2017

For the last 29 years, our lives centered around our annual visit to see our sister Kanizan in Lahore.

It takes us a year to save a few thousand rupees for the trip. My sister and I, cramp up behind our brother, as he rides his motorbike for six hours non-stop. We usually do not have enough money for food let alone an overnight stay, so our brother rides directly to Data Darbar to make it in time for the langar. While he’s being pushed and shoved in the massive crowd trying to get us food, Imrana and I, reserve a spot for the three of us to spend the night. The following morning, we need to be at the medical facility at 9am sharp.

When we get there, my sister and I are separated from our brother. Our bags are emptied; we are made to remove our shoes, and are patted down as everyone else looks on. We are then made to wait. A lady from ‘a good family’ arrives, escorted by her driver. We are told she’s visiting her son. She is swept through.

At 11am, in ward-D, we finally get to meet Kanizan. Her skin is pale. The wrinkles on her face testify to her schizophrenia, third-degree police torture, and the 29 years of her life wasted as a prisoner on death row.

She remains silent. Her eyes are blank, yet they ask many questions. Questions she can never articulate and questions we can never answer.

Kanizan’s life ended before it even started. She grew up without her mother, mothered by her own father, raised the children she was accused of murdering, and was murdered by a justice system which was supposed to protect her.

How does one console someone like her? How do you tell someone who has spent 29 years on death row, that we still don’t know when she will be a free woman? Or if she will be one at all. But, Kanizan does not speak. And part of me is glad she does not, because in that moment, nor can I.

I still cannot understand how she got here. How she went from being someone we knew, to someone we can no longer recognise?

Kanizan was working as a maid for a rich family. Her fate changed on the night when the wife of the landlord and his five children were murdered in Kamaliya due to a land dispute. To take over his land, they accused him of being in love with a much younger woman: my sister. Together, the landlord and Kanizan were accused of the murders. Kanizan had brought up those children as her own.

She was 16 years old. The police recorded her age as 25.

The events leading up to her arrest pale in comparison to what was about to follow. To make her confess to crimes she never committed, the police subjected her to torture. Women in our village, never interact with men outside of our immediate family. But Kanizan spent nights trapped in a jail cell as unknown policemen reduced her to pulp, beating her while hanging her from a fan.

A well-wisher once tried explaining third-degree police torture to our family to help us understand Kanizan’s mental illness. Men subjected to torture are usually stripped naked, suspended from a pole with their right arm and left leg tied together. They are then paraded around the jail as interrogators strip them of their dignity. They are unable to sleep for years as a result.

Imagine her being stripped naked. Imagine a woman being grabbed by her hair, her body violated. Imagine the rest of them cackling as she pleads with them. Imagine her giving up as all of her pleas for help and forgiveness drown into the silence of the night. Imagine her will to live being sucked out of her with each touch. Now, it’s not very hard to imagine how her mind gave up on her.

No court of law, no quality of healthcare, and no amount of commiseration can ever compensate Kanizan Bibi.

President Mamnoon Hussain has dismissed her mercy petition, despite the evidence of her illness. Despite the fact that Kanizan is unable to speak or defend herself because of torture inflicted by the police.

Kanizan’s silence should not deafen the government to her plight. We beg President Mamnoon Hussain to accept her mercy petition, and save her from a life that has already killed her many times over.

— As narrated to Alhan Fakhr, the media and communications officer at the Justice Project Pakistan, by Ghulam, the inmate’s sister.