China's futuristic library: A whole lot of fiction

Those rows upon rows of book spines are mostly images printed on the aluminium plates

November 22, 2017

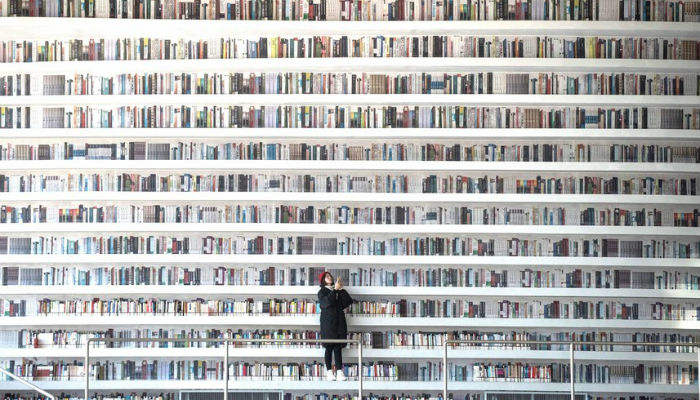

TIANJIN: A futuristic Chinese library has wowed book lovers around the world with its white, undulating shelves rising from floor to ceiling, but if you read between the lines you'll find something is missing.

Those rows upon rows of book spines are mostly images printed on the aluminium plates that make up the backs of the shelves.

Pictures of the sleek Tianjin Binhai Library have gone viral on Chinese social media and abroad since its opening last month, with headlines trumpeting it as the "world's best library" and a "book lover's dream".

On weekends, an average of 15,000 visitors flock to the six-storey space in the eastern port city of Tianjin.

Designed by Dutch architectural firm MVRDV, the building looks like an eye when viewed from the still unfinished park outside, with a spherical auditorium as the iris at its centre.

The library contains 200,000 books and it has grand ambitions to grow its collection to 1.2 million.

But readers expecting to pluck tomes from most of the terraced shelves are in for a surprise. Most books are in other rooms with more classic library bookshelves.

"There's quite a big difference between the photos and reality," said Jiang Xue, a 21-year-old medical student left perusing one of the more robustly stocked sections: propaganda about the ruling Communist Party's recent congress.

'Give it a soul'

An essential part of the original concept was for the upper bookshelves to be accessible via rooms placed behind the atrium, MVRDV told AFP, but a fast-tracked construction schedule forced them to drop the idea.

The decision was made "locally and against the MVRDV's wishes," its spokeswoman Zhou Shuting said.

But Liu Xiufeng, the library's deputy director, blamed the design for putting them in a bind.

Liu said the plan finally approved by authorities stated that the atrium would be used for circulation, sitting, reading, and discussion, but omitted a request to store books on shelves.

"We can only use the hall for the purposes for which it has been approved, so we cannot use it as a place to put books," Liu laughed, adding that they would likely soon have to remove all those temporarily on display.

There's another quirk: The irregular white stairs have proven hazardous for selfie-snappers with eyes glued down to their phones or up at the stylish ceiling.

"People trip a lot. Last week an old lady slipped and hit her head hard. There was blood," said one guard, who yells warnings at visitors.

China is notorious for building astronomically expensive cultural facilities that open to great fanfare, only to end up standing empty without concerts or programming to fill them.

It is also no stranger to controversy over book faking.

Last month, Beijing's Liyuan Library, a non-profit space internationally recognised for its beautiful wooden reading spaces and design, suspended operations after its books were found to contain pirated and explicit content.

But the Binhai library's viral image has boosted readership, with checkouts quadrupling since the opening.

The children's rooms downstairs bustled with families flipping through illustrated stories.

"The architecture they completed is like a newborn infant delivered into our hands. Now it's up to us to give it a soul," said Liu.

'I don't touch real books'

Building membership, however, may prove a challenge for Liu in a country where readers increasingly flip through novels on smartphone apps.

The popularity of reading apps has led to a boom in online publishing.

Shares in China Literature -- the country's biggest player in the business, comparable to Amazon's Kindle Store -- shot up more than 60 percent on their debut on the Hong Kong stock exchange last week, after raising $1.1 billion in an IPO.

Yuan Jiwen, an e-commerce major fond of online novels set in the Three Kingdoms period, held an unread paperback like a prop as he people-watched in the atrium.

"I don't usually touch real books," he said. "But it feels appropriate to be holding one here."