Women in the law

Pakistan is the only country in South Asia to have never had a female Supreme Court judge

January 13, 2018

In 1923, nearly a century ago, the Legal Practitioners’ Act was amended to remove the legal bar on women from practising law. The amendments were in response to the refusal of high courts in Calcutta and Patna to allow qualified women lawyers to appear in courts as they were considered “unfit for the duties of the legal profession”.

Opposing the Bill, Maulvi Mian Asjad-ul-Ulah from Bhagalpur Division, said in the legislative assembly that such an amendment would be antithetical to justice, as “susceptibility to female charms” would make male judges and witnesses partial towards women advocates, and in the long run, women would “take the practice away from men”.

Another member of the legislative assembly, Khan Bahadur Abdur Rahim Khan from the then North-West Frontier Province, supported the bill, but only because “the presence of ladies as barristers in court will make the judges and the barristers behave themselves”.

Since then, women lawyers and judges in the subcontinent have come a long way. However, sentiments constituting similarly pernicious gender stereotyping are still being repeated in Pakistan almost a hundred years later.

For example, there have been petitions to the Federal Shariat Court to declare the appointment of women judges contrary to Islam. While the FSC has dismissed the petitions, it noted that to prevent men from “entertaining false hopes”, the state could prescribe some garment that could “conceal the dress and womanly adornments” of women judges.

The Council of Islamic Ideology has also said that only women over the age of 40 should become judges as that is when “women no longer remain attractive or marriageable”.

In a private conversation, a retired judge of the Supreme Court said that because of their “caring and sensitive nature”, women lawyers were unsuitable for “hard legal matters” and if they are to practice, they should focus their practice on “softer” areas of the profession, such as family law – stereotypes women lawyers and judges continue to hear as a matter of routine.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, such sexist attitudes have contributed to the near-exclusion of women from positions of authority and leadership in Pakistan’s legal profession and the judiciary.

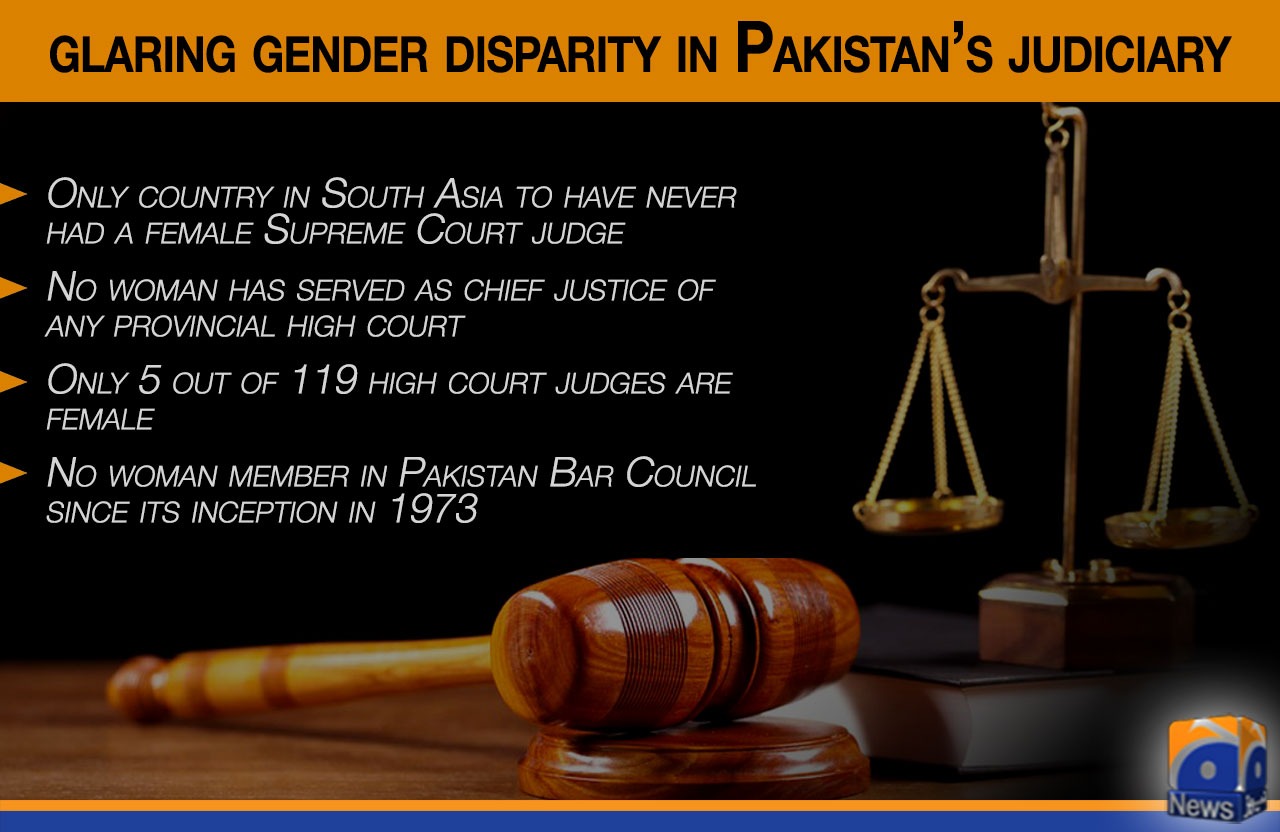

Pakistan is the only country in South Asia to have never had a woman Supreme Court judge (India, Nepal, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka have all had women serve in their highest courts); no woman has served as the Chief Justice of any of the provincial high courts; and currently, only five out of Pakistan’s 119 high court judges – just 4 per cent - are women.

The Bar to shows similar gender imbalance. Since its inception in 1973, the 23-member Pakistan Bar Council, the highest regulatory body for lawyers in the country, has never had a woman member. Bar associations fare better, but there too Asma Jahangir is the only lawyer to have been elected as president of the Supreme Court Bar Association.

Despite such glaring gender disparity in the legal profession, all institutions of the state appear disinterested in acknowledging, let alone addressing, the problem.

There was some hope in 2016 when two bills were introduced in the Senate and the National Assembly noting that women are underrepresented in the Supreme Court. However, the solution proposed by the bills was to institute quotas of 33 per cent and 25 per cent respectively for women judges in the Supreme Court - a problematic remedy that would not have been effective in addressing the gender imbalance in the judiciary, let alone the legal profession.

The bills, of course, failed in both Houses. However, the reasons for the Government’s opposition to the bills are telling and included simplistic assertions that “lack of interest” on the part of women lawyers and judges has led to their absence from the Supreme Court and there are no institutional hurdles that prevent them from leadership roles in the legal profession.

This casual dismissal of the glaring gender disparity in the judiciary is a disappointing abdication of the Government’s duty to redress that imbalance and an indictment of its commitment towards achieving full and equal participation of women in public life.

There are many reasons for women’s under-representation in the legal profession. Some reflect the general obstacles and discriminatory societal attitudes towards women that permeate other areas of their professional and private life. There is, for example, now greater acceptance of women’s education, but women as professionals are still viewed with suspicion.

Where women work, there is greater opposition towards women entering traditionally “male” professions such as the law. And where women choose to practice as lawyers, the expectation often is that they will discontinue once they get married and have children. Similar to other fields, women from elite backgrounds with family members in the legal profession are better able to gain acceptance and success than their counterparts from less privileged backgrounds.

Some challenges faced by women lawyers and judges, however, are more specific to the legal profession, many of which hamper women’s equal participation in the law.

One key issue is the lack of transparency in the judicial appointments process for judges of the high courts and the Supreme Court.

According to the Constitution, a nine-member judicial commission, comprising largely of senior judges, is responsible for nominating judges for the superior judiciary and recommending them to a parliamentary committee for approval. Currently, all nine members of the judicial commission are men.

The criteria on which the judicial commission shortlists candidates are not transparent and the commission’s proceedings and deliberations are not made public. In the larger context of discriminatory practices and attitudes in the legal profession, such secrecy often works to the detriment of women and leads to the perception of bias in the appointments process.

It is therefore critical that transparent and holistic selection criteria are elaborated in relevant legislation and in rules for judicial appointments. Such criteria, for example, should expressly define merit so as to include the goals of judicial diversity and gender equality – as is done in a number of jurisdiction globally including South Africa.

Second, the underrepresentation of women in the judiciary cannot be separated from the near-absence of senior women lawyers in the country. Like the judiciary, gender imbalance is also stark in the legal profession, especially at senior levels. A long overdue measure, therefore, is amending the Legal Practitioners and Bar Councils Act, 1973, so as to give real effect to the duty of bar councils to eliminate discrimination and promote equality in the legal profession.

It also includes addressing sexual and other forms of harassment and discrimination that continue to be pervasive in the legal profession. The judiciary and the Bar are largely unaccountable institutions and complaints of sexual harassment and other misconduct against lawyers and judges are rarely investigated. There is also resentment towards making any kind of accommodation for women lawyers and judges, from maternity leave and childcare, which pushes more and more women away from the legal profession.

It is unfortunate that the debate around women’s representation in the legal profession and the judiciary started and ended with the calls for institution of quotas for women judges in the Supreme Court.

Instead, what Pakistan urgently needs are sustainable and effective efforts to advance women’s representation within the judiciary and ultimately achieve gender parity in the legal profession. Doing so will require express and lasting support and commitment from a range of actors including members of the government and parliament; the Chief Justice and other senior members of the judiciary; as well as bar councils and associations.

Such support and commitment, regrettably, are yet to be seen in any of these institutions.

Omer is a legal adviser for the International Commission of Jurists. She tweets @reema_omer

Note: The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Geo News, The News or the Jang Group