They say that politics is the art of the possible. Getting elected, especially to Pakistan's upper house of Parliament, requires the craft of forging alliances with bitter rivals. What took place in the Sindh Assembly on Saturday is one example of this artfulness.

It is difficult to explain the outcomes of the recent Senate polls in Sindh—how a party with only nine lawmakers grabbed a Senate seat, while the second largest party in the province with 37 members in a house of 165 could barely manage one seat.

However, analysis of publicly available data on the vote count reveals how some lawmakers voted for candidates from opposing parties and how some candidates drew support from across party lines to win their tickets to the upper house of Parliament.

For the Senate, Pakistan employs the complicated system of single transferable vote. What does that mean? In simple words: Voters mark their order of preference for one or more candidates on the ballot. A candidate wins if his/her votes exceed a minimum threshold. The value of the candidate's votes exceeding the threshold are passed on to the second preference candidates, and the counting exercise continues until all seats are filled.

The vote is conducted through secret ballot, so it is almost impossible to ascertain the identity of the voter. But, by analysing the flow of the excess votes, one can tell how many MPAs betrayed the trust of their own party by voting for rival candidates against party policy.

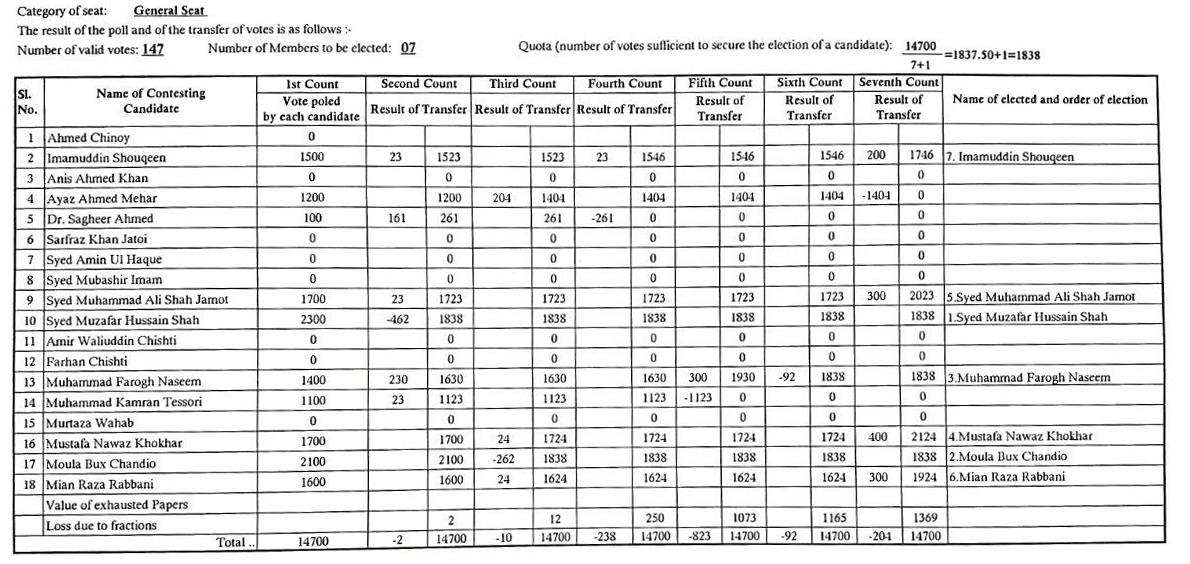

A total of 147 Sindh MPAs voted on Saturday to elect senators on seven general seats, and the Election Commission calculated the minimum threshold to win at 18.38 votes.

On the first count, the Pakistan Peoples Party's Maula Bux Chandio received 21 votes, M Ali Shah Jamot and Mustafa Nawaz Khokhar received 17 votes each, Imamuddin Shouqeen got 15 votes, Ayaz Ahmed Mehar received 12 votes, while outgoing Senate chairman Mian Raza Rabbani got 16 votes. From the Muttahida Qaumi Movement-Pakistan (MQM-P), which has 37 lawmakers in the provincial assembly, Farogh Naseem received 14 votes while Kamran Tessori received 11 votes. Only one vote went to Sagheer Ahmed, an MPA from the Mustafa Kamal-led Pak Sarzameen Party (PSP) which was formed as a split from the MQM.

But Syed Muzaffar Hussain Shah of the Pakistan Muslim League-Functional (PML-F)—an opposition party with only nine MPAs, less than half the number of required votes—picked up 23 votes, more than even candidates of the PPP which governs Sindh. It is obvious that MPAs from outside the PML-F voted for Muzaffar Hussain Shah, but looking at the transfer of his votes on successive counts gives us a better idea of where these voters may have come from.

Shah was first to be declared elected, and the value of his surplus votes (23-18.38=4.6) was transferred to other candidates marked as second preference by his voters. Three of these voters chose to exhaust their votes by not marking any further preferences, two chose PPP’s Imamuddin Shouqeen and Syed Mohammad Ali Shah Jamot, while one picked MQM-P’s Kamran Tessori, with the value of their votes passed on at the value of 0.23 each.

It is worth noting that the PML-F and MQM-P sit on the opposition benches in the Sindh Assembly and their MPAs are fierce opponents of the PPP provincial government. It is unclear whether these three MPAs belonged to the PPP, MQM-P, or PML-F, but what is clear is that their loyalties are split across party lines and their votes played a key role in getting Shah re-elected as senator.

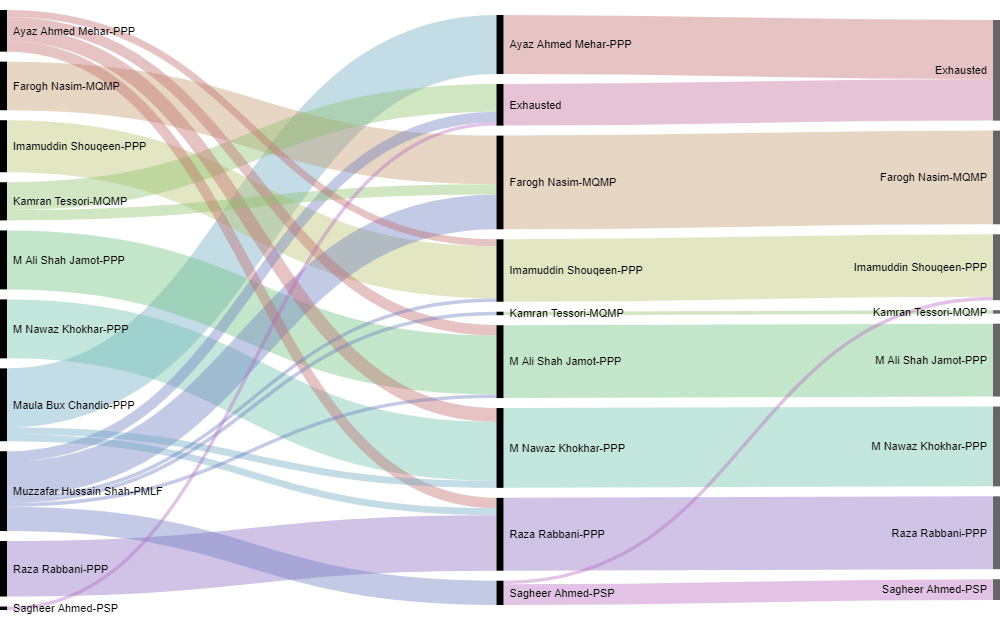

The interactive data visualisation below shows transfer of excess votes from one candidate to another. On the left are first count votes, and on the right are votes in the final count.Hover over nodes to see how marginal value of votes flowed from candidate to candidate based on voters second or third preference.

Bahadurabad vs PIB: Who betrayed who?

Kamran Tessori, whose Senate nomination became the main bone of contention and led to bitter infighting between the MQM-P's Bahadurabad and PIB Colony groups, failed to garner more than 11.23, and therefore three of his votes were transferred to the Bahadurabad group's Farogh Naseem.

It is likely that these three voters were MQM-P MPAs, influenced by a last minute 'truce' between the Bahadurabad and PIB groups as they agreed on Naseem and Tessori as the party's final candidates. But not everybody, it appears, was happy with this arrangement.

Tessori's remaining eight voters, likely from the party's PIB Colony group, chose to discard their votes rather than mark the Bahadurabad group candidate as their second preference. The absence of these eight votes put Naseem in a precarious position, with two votes short of the minimum 18.38 required to win.

However, 10 of the remaining voters who marked PML-F candidate Muzaffar Shah as their first preference chose MQM-P's Farogh Naseem as their second preference. These 10 votes were transferred at the value of 0.23 each to Naseem, raising his final count to 19.3 votes and helping him across the minimum threshold of 18.38. Without these 10 second preference votes, the MQM-P might not have been able to secure even a single seat from the Sindh Assembly.

So, where did these 10 votes come from? There are three possibilities. If they were MQM-P lawmakers, it is embarrassing for the party as they chose the PML-F candidate first. How did Shah manage to turn them? Has the internal turmoil demotivated MQM-P legislators so much that they choose rival party candidates over their own? Or, as Farooq Sattar claims, did money really play a role in the Senate elections? The second possibility, highly unlikely, is that these MPAs neither belonged to the MQM-P or PML-F. The third possibility is more interesting. The PML-F doesn't have 10 MPAs in the Sindh Assembly. Did the MQM-P's Bahadurabad group offer one or two votes to the PML-F in exchange for eight or nine second preference votes, thus raising the value of their one or two their votes to 2.3? From the data released by the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP), it is impossible to know for sure. Perhaps Farogh Naseem or Syed Muzaffar Hussain Shah himself can answer these questions.

The MPA who voted for three different parties

The graphic below illustrates how votes from different Sindh MPAs flowed from one candidate to another on successive counts. As can be seen, not every voter switched loyalties, and some chose to discard their votes rather than vote for another candidate. At the same time, not every candidate's votes were transferred, so it can never be known who their voters marked on their second and third preferences.

Findings from the election data reveal that at least 20 MPAs from the Sindh Assembly voted for candidates from at least two different parties. The most interesting, however, is the case of the MPA who marked candidates from three different parties as his/her first, second, and third preferences.

Seven of those MPAs who voted for Muzaffar Hussain Shah as first preference chose the PSP’s Sagheer Ahmed as their second choice. The value seven votes were transferred to Sagheer Ahmed at 1.61 (7x0.23). Speaking to the media on Sunday, Mustafa Kamal claimed that members of his party voted for the PML-F candidate, so it is likely that all of these voters belonged to PSP. At the same media talk, the PSP chief raised the issue of horse-trading and how others had tried to ‘buy’ the votes of his party members.

Sagheer received one vote in the first count, taking the total value of his votes to 2.61. Since this was below the minimum threshold, his votes were further transferred on the fourth count. Seven of these chose to discard their votes, but one marked his next preference for PPP's Imamuddin Shouqeen. The fact that this vote came from Muzaffar Hussain Shah can be proved by looking at the value of the one vote transferred to Shouqeen: 0.23, the same value at which it was calculated when passed on from the PML-F candidate to PSP's Sagheer Ahmed.

Given the PSP's strength in the Sindh Assembly and the number of votes cast for their candidate, it is highly likely that this MPA who voted for three different parties belongs to PSP. However, that cannot be said with complete certainty. The possibility exists that this MPA belongs to the PML-F, or even an entirely different party.

From the data released by the ECP, it is impossible to ascertain the identities, party affiliations, and voting behaviour of individual MPAs in Senate election. It does, however, help us get a better understanding of how representatives of the people directly elected by Pakistani citizens choose to use their vote when it comes to electing members of the upper house of parliament.

—Sajjad Haider is Special Projects Editor at Geo.tv. He tweets at @sajjadhaider1