The paradox of Imran Khan’s populism

Mr Khan has made three speeches now and they highlight a pattern and a struggle between being a reformist statesman and an angry populist

August 25, 2018

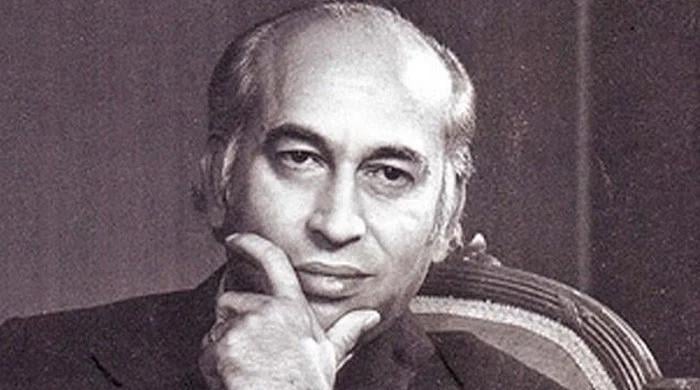

Prime Minister Imran Khan in his first speech could have announced a nuclear war on Swaziland, Africa, or radical land reforms and it would not have mattered since his diehard supporters, and now his enthusiastic detractors, have a template where he can’t do anything wrong or right depending on one’s leaning. A couple of hours after the speech we would have been back to how many pakoras were served by previous regimes at press conferences.

Prime Minister Khan spoke to a deeply divided nation where politics is no longer a difference of opinion but an indication of a person’s moral worth. Opposition leader Khan has been the worst offender in bringing us here, however, many others have contributed; one example of how successful and pervasive Khan’s influence has been on political language and idiom is that his most fierce opponents (youthful PML-N cadres) now often speak the same language of accusation, ridicule and abuse.

Mr Khan has made three speeches now and they highlight a pattern and a struggle between being a reformist statesman and an angry populist. The acceptance speech, while being high on rhetoric, was still measured, outlined some vision and was conciliatory. The National Assembly speech was of an opposition leader vengefully shadowboxing a past, non-existent government.

The high point of the first address to the nation was his desire for social reform and he spoke about stunted growth, infant mortality, malnutrition, out of school children, child abuse, civil service and police reforms and functional local government institutions. To speak candidly about these grave challenges is commendable and a reason for optimism. Many of the issues that he addressed are provincial subjects and will require him working with provincial governments, even those which are held by his political opponents. Conspicuous by absence were the core areas of the federal government’s mandate such as foreign policy, internal security, violent extremism and civil liberties.

Mr Khan’s reform agenda seems to focus on economic and social rights, while pretending that economic prosperity can be divorced from creating an egalitarian, pluralistic and inclusive society — a mistake that Nawaz Sharif and affiliates took to an art form, where no problem was big enough to not be solved by flinging a flyover at it.

Khan did not speak about the persecution of religious minorities, blasphemy law or expressed the general ambition for a tolerant polity. A brief glance at the Pakistan cyberspace will disabuse anyone of the notion that education and technology alone can instill tolerance and inclusion.

Both Khan’s supporters and critics insist on viewing it as a binary where one can either focus on out of school children or freedom of expression. This is fallacious almost everywhere, more so, in our multicultural, federal democracy facing an enormous economic crisis and grappling with extremism. Pakistan will have to become a modern, progressive and accountable democracy to send children to school and curb blasphemy law and other repressive laws.

Visible in Mr Khan’s first address to the nation was the paradox of populist politics in Pakistan; the very structures and institutions that deliver power to the populist politician also define his sphere of limited influence. Hence, foreign policy and internal security remain out of bounds for him. However, civilian supremacy will not be installed because the law says so (it should, however it wouldn’t) but by building functional, viable civilian institutions and relying on them.

The lowest hanging, easiest and laziest populism of faux austerity in samosas and pakoras will not do. This requires hard, unglamorous work of strategic capturing space from unelected bureaucracies, and that will be hard for Mr Khan as it was for Mian Nawaz Sharif. However, the onus now is higher for Khan since he has politicised (a good thing) large population of the urban youth population and has made them angry at his opponents, in specific, and the world, in general.

han can either attempt to politically de-radicalise his supporters or be caught up in a vicious cycle of pandering, appeasement and the resultant even more radicalization and anger. One fear is that to compensate for his razor-thin majority and the personal knowledge of how even the seemingly most stable governments can be dismantled, he might resort to more easy and angry populism to cultivate a power source outside of the parliament to indemnify himself, when the cycle for going after the next civilian villain comes around. That would not work. Civilian structures will either be strong enough to withstand interventions and intrigues from outside or they won’t be; it is not person specific. As a proponent of a functional local government system, one would expect Mr Khan to see the wisdom of provincial autonomy and the eighteenth amendment since it is the same logic, and this logic of participatory democracy at all tiers of government is the real insurance policy.

Along with the usual supporters, there is also a new cadre of “optimists” who suddenly see new virtues in Mr Khan’s every syllable. On the other end of the spectrum are those who would want him to fail so bad that at times it seems that they are rooting for the collapse of Pakistan’s economy.

Most want him to succeed and wish for hope, however that success can only happen if there is hope for Pakistan’s religious minorities, women, marginalized ethnicities, agricultural and industrial workforce and many other groups left behind on the “development” agenda.

Ijaz is a lawyer and the country representative for the Human Rights Watch.

Note: The views expressed are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Geo News or the Jang Group.