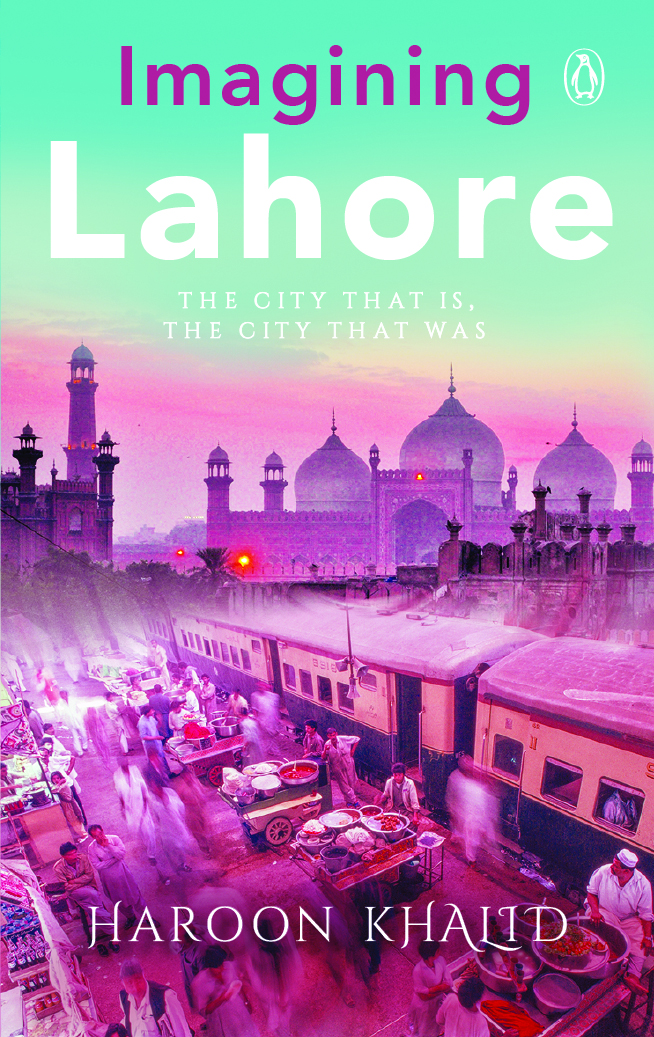

Imagining Lahore: The city that is, the city that was

An excerpt from Imagining Lahore: The city that is, the city that was by Haroon Khalid

October 03, 2018

The needle of the empty syringe is still stuck to his arm. His eyes are forced shut. I can sense him struggling beneath his eyelids but the heroin proves to be stronger. He has fought this battle many times. He knows how futile it is. His head hangs to one side. Saliva dripping from his mouth sticks to his matted beard. I can almost feel the lice swimming in his hair upon my own. His brown kameez has patches of liquid — sweat, urine. A bag of rice is tied to one of his fingers. It is a small serving that he won’t be able to share with his heroin-addict friends who sleep next to him in the last remaining relic of a serene Mughal garden.

There is chaos all around them —bikes, wagons, cars, donkey carts, rickshaws and buses vie for space, the one-way rule having long been abandoned. A traffic warden stands to one side, in his full-sleeved shirt, under the shade of a young tree that will soon be uprooted. He removes the straw from his glass of sugarcane juice and gulps the liquid down thirstily. He will only step in when there is a jam. Otherwise, he knows there is nothing much he can do to regulate the traffic as long as work continues on the Orange Line.

The structure of Chauburji is almost like a blot of paint dropped accidentally on an intricate postmodernist painting. There is a sadistic charm to the pandemonium of Lahore. There is symmetry in its disorder. Every house is as abruptly constructed as the one next to it, all of them audaciously flouting building laws. Packed together, each new building is taller than the previous one. This is one of the most densely populated areas of the city, with more than 31,000 people per square kilometre.

The government too competes in its own way. Renovation of roads over the past several decades has meant the application of successive layers of tar, so that the ground floor of each house is at a different level. Even the electricity poles find themselves haphazardly aligned, bent at their own particular angle. A jungle originating from these poles heads off in different directions.

In the middle of all this is Chauburji, a structure laid according to a perfect plan, with four minarets in each corner of the square building. Perfectly shaped floral and geometrical patterned mosaics decorate its walls. Its neatly aligned windows, arches and niches are almost an assault to the eyes of a visitor accustomed to the mayhem of Lahore. The structure belongs in a different city, in a city of gardens that no longer exists, a city that was the playground of Mughal royalty, a city of thousands, yet a city that only belonged to a handful. This, then, is our revenge, imposing on these ancient relics of oppression our authority. We introduced anarchy where once there was order. We ripped apart the symmetry of these structures and enforced upon them our own version of reality.

All that survives now is this lone gateway with its four minarets that earn it its name—chau (four) burj (minarets). The vast orderly garden, streams extracted from the nearby River Ravi, the pavilions where Mughal royalty would rendezvous, the glass palaces where the only reflection was that of royalty and the fountains that danced with the music—all these have long disappeared.

There are several contending claims to the construction of this garden and Chauburji. According to one of them, the garden was created by Zeb-un-Nissa, the ‘Sufi’-inclined poetess and daughter of the ‘puritanical’ Aurangzeb. Perhaps what gives credence to this claim is the presence of Zeb-un-Nissa’s alleged mausoleum a little distance away.

The locality of Nawa Kot, or ‘new fort’, is only a few kilometres from here. Its name belies its condition. Thousands of houses and buildings are crowded together in this small locality, competing for space. Giant banners advertising dubious visa consulting businesses hang from every other building. Like Chauburji, there was a spacious garden here at the end of the eighteenth century, when Punjab, and particularly Lahore, was experiencing a new dawn. For almost a century after the decline of Mughal influence, Punjab and Lahore had been in a state of chaos. Squatters were gradually taking over symbols of Mughal royalty, their gardens transformed into jungles. Warlords held sway over Punjab, and the city of Lahore had been divided between three Sikh warlords. This anarchy was quelled by Ranjit Singh’s conquest of Lahore in 1799.

If it hadn’t been for one Mehr Muqamudin, a guard at the Lohari Darwaza, one of the twelve gateways of Lahore leading into the walled city, perhaps Ranjit Singh’s march into Lahore, which symbolically marked his capture of the throne of Punjab, would have been delayed for a little while longer. Mehr Muqamudin opened the gate, allowing his armies to march into the city peacefully. As a reward for his loyalty, Ranjit Singh allotted him this garden. Razing most of the existing structures, Mehr Muqamudin established a fortified locality for the people of his ancestral village and named it accordingly.

Tucked away amidst tall buildings, in the locality of Nawa Kot, is the tomb believed to be of Zeb-un-Nissa, a little building, petrified, unsure of what the future will hold for it. For now, there is hope. A government board has been placed upon its stout structure, identifying it as protected property. But danger looms at the gate. Neighbouring shops have over time extended their entrances, taking over vacant land around the tomb. Encroaching upon this protected monument is a bamboo seller’s shop, with several of his freshly made ladders leaning greedily into the complex.

Built on a raised platform, the mausoleum is a single-storey structure with a wide dome on the top, typical of Mughal architecture. Two ancient trees, banyan and berry, regarded as sacred in the folk Islamic and other religious traditions of India, stand guard on either side, protecting the grave regarded as that of the Mughal princess. Abandoned by time and fate, the grave lies at the centre of the mausoleum.

At certain points, the brilliance of the sublime Mughal architecture shines through centuries of decay. Red-and-yellow floral patterns that form honeycombed shapes called muqarnas emerge on closer inspection. Beneath the crumbling floor, the geometrical patterns of the bricks merge into ever-growing larger ones. The red stone used widely in other Mughal buildings makes an almost niggardly appearance here, at the base of the structure, with carved floral and geometrical designs chiselled to perfection. At a time when multistorey buildings are raised in a matter of months, the meticulous attention paid to the finishing of this structure is almost embarrassing.

Excerpted from Imagining Lahore: The city that is, the city that was by Haroon Khalid (Viking, August 17, 2018)