Dirt covers almost everything around Karachi's captivating 150-year-old Empress Market after an anti-encroachment drive. A thicker layer of dust, however, shrouds the historical significance of the 120-feet-tall architectural masterpiece. Very few know that the artistic cover of the Empress encroaches upon a bloody chapter of the Subcontinent's history.

The governor of Bombay (now Mumbai), James Ferguson, laid the foundation stone of the Empress market in 1886. However, the market would never have been constructed was it not for the 1857 Sepoy mutiny, the widespread rebellion against British rule in India.

Does all this sound confusing? It will make sense soon.

"This place used to be an empty, barren ground. It was a cantonment area," Akhtar Baloch, a researcher on Karachi history tells Geo News.

"The façade of the Empress Market was designed by the then-chief municipal engineer Mr James Strachan but history itself was the chief architect of this masterpiece."

In 1843, Sindh fell into the hands of the British and the sun was ready never to set on the British Empire. At the same time, the seeds of independence were sown into the colony. Within two decades, seeds grew into trees and bore fruit. The rebellion against the British Raj broke out in May 1857 from Meruth, and it rapidly reached the coastal lands of Sindh.

"In Karachi, the fire of rebellion erupted from the lines of 14th Desi pedal Fouj. Motivated by the spirit of independence, 38 sepoys escaped the cantonment area. The plan was foiled and eight of them were killed on their way. The rest were arrested and presented before a jury which sentenced them to death," says Madad Ali Sindhi, a researcher at the Sindh Cultural Department.

"In his biography, Sir Bartle Frere wrote that the rebels were congratulating each other before they were executed," said Madad Ali.

The execution was not carried out on a normal firing range—the British had decided to make it an example for the voices of dissent against colonial power.

"The sepoys were executed brutally. Cannonballs were fired on them and their corpses buried at the same barren ground. They were not even complete corpses but mutilated parts," Mr. Baloch recalls history.

"By the time it was revealed to the citizens, and knowing the importance of the place, some threw flowers and while others lit candles at the location. The practice gained soon momentum and people started paying frequent visits to pay homage to their freedom fighters."

This was not acceptable to the colonial masters, but any action bore the risk of igniting fire in the ashes of resistance.

"The British rulers were alarmed of the soaring popularity of this particular place. They were concerned after the 1857 mutiny, but came up with a smart solution. It was decided that a market would be built on that empty ground," says Baloch.

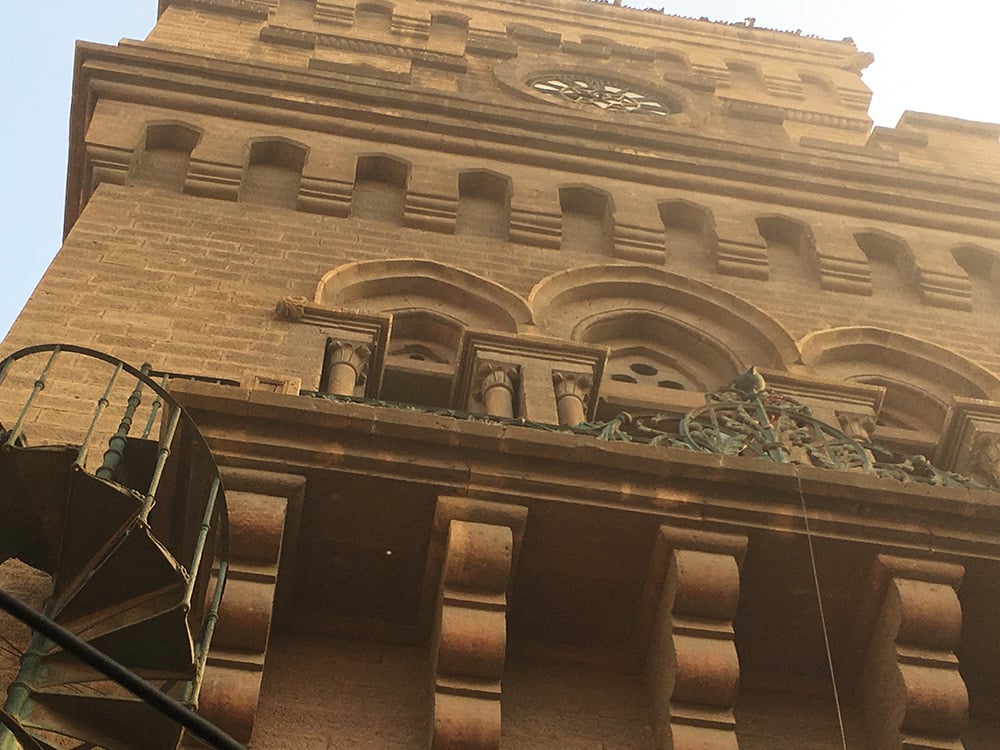

The British feared the locals would build a monument to honour the executed sepoys, so instead they built the Empress market at the place location to commemorate Queen Victoria.Governor Ferguson was asked to lay the foundation stone in 1884, the same day that the foundation of the Merewether Tower was also laid. Red stones were brought from Jodhpur (now in India) all the way to Karachi. The construction took four years and cost 0.12 million rupees at that time. The Empress was decorated with a clock-like a jewel in its crown, and fountain was installed in the heart of the market. The architectural masterpiece was christened the Queen Victoria Empress Market, marking the Golden Jubilee of the British Queen.

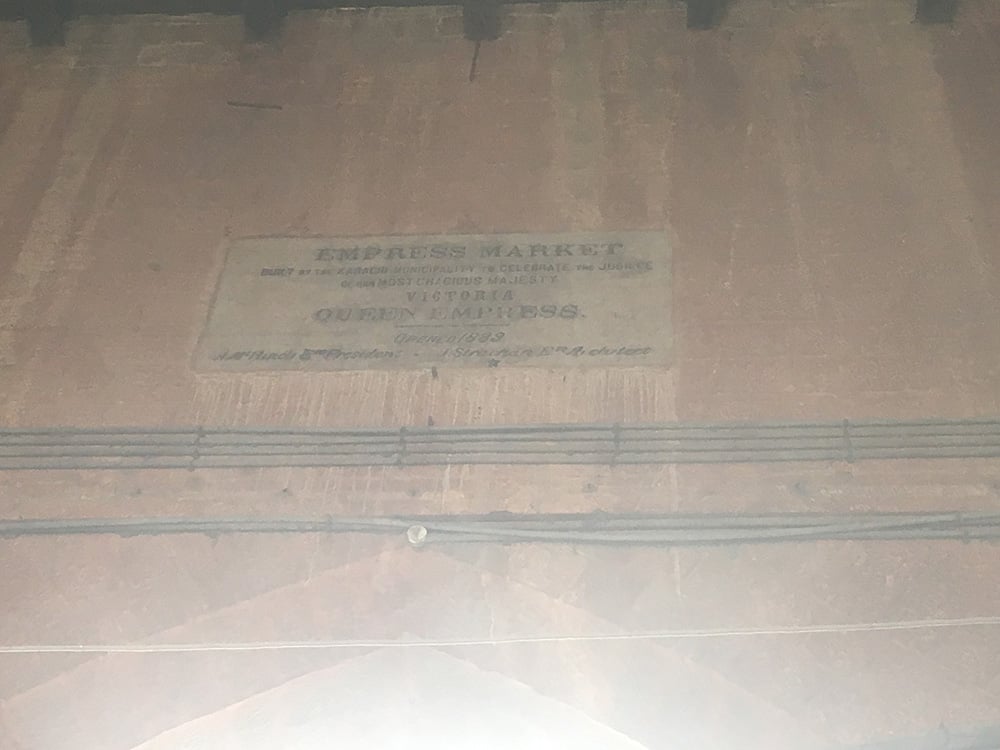

If you look at the top after passing the main entrance of the market, you can still read the date of its foundation inscribed on a marble slab.

Aside from its distinct historical significance, the Empress is also unique in architecture as well. The construction was carried out by a British firm, but two of the designers were locals. The style of architecture is an unusual combination of Indian and Roman style of construction, also called the Indo-Gothic style. Its four galleries, designed like those in Mughal era buildings, provided accommodation for 280 shops. At the time of construction, it was one of only seven markets in Karachi.

For 161 years, the structure stood firm while massive urban encroachment continued to surround it. After the operation, the Empress seems to be in a deep thought — perhaps, waiting for a new era to usher in.

After all these years, the regal ironwork on the main gate has lost its original charm. Once you enter the market, a spiral staircase leads you to the upper of the building. The clock on the exterior stopped working long ago, but time did not. It also seems that mechanical parts of the clock tower are either missing or probably stolen. From the galleries, one can see the bustling roads and shopping markets of Saddar, but the fountain in the heart appears to have disappeared. After ages, the structure of the market was washed with water and dusting was done with heavy blowers. Unfortunately, stains on the pages of history are harder to wash.