Hong Kong's surveillance-savvy protesters go digitally dark

Hong Kong's tech-savvy protesters are disabling phone locations, using cash, and purging their social media conversations

June 16, 2019

HONG KONG: Hong Kong's tech-savvy protesters are going digitally dark as they try to avoid surveillance and potential future prosecutions, disabling location tracking on their phones, buying train tickets with cash, and purging their social media conversations.

Police used rubber bullets and tear gas to break up crowds opposed to a China extradition law on Wednesday, in the worst unrest the city has witnessed in decades.

Many of those on the streets are predominantly young and have grown up in a digital world but they are all too aware of the dangers of surveillance and leaving online footprints.

Ben, a masked office worker at the protests, said he feared the extradition law would have a devastating impact on freedoms.

"Even if we're not doing anything drastic — as simple as saying something online about China — because of such surveillance they might catch us," the 25-year-old said.

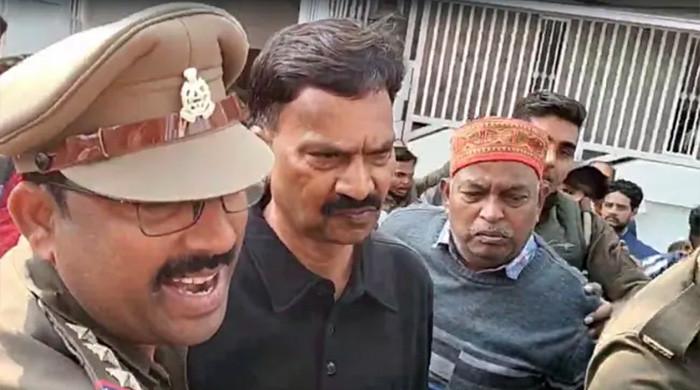

This week groups of demonstrators donned masks, goggles, helmets, and caps — both to protect themselves against tear gas, pepper spray, and rubber bullets, and also to make it harder for them to be identified.

Many said they turned off their location tracking on their phones and beefed up their digital privacy settings before joining protests, or deleted conversations and photos on social media and messaging apps after they left the demonstrations.

There were unusually long lines at ticket machines in the city underground metro stations as protesters used cash to buy tickets rather than tap-in with the city's ubiquitous Octopus cards — whose movements can be more easily tracked.

In a city where WhatsApp is usually king, protesters have embraced the encrypted messaging app Telegram in recent days, believing it offers better cyber protection and also because it allows larger groups to co-ordinate.

On Thursday, Telegram announced it had been the target of a major cyber attack, with most junk requests coming from China. The company's CEO linked the attack to the city's ongoing political unrest.

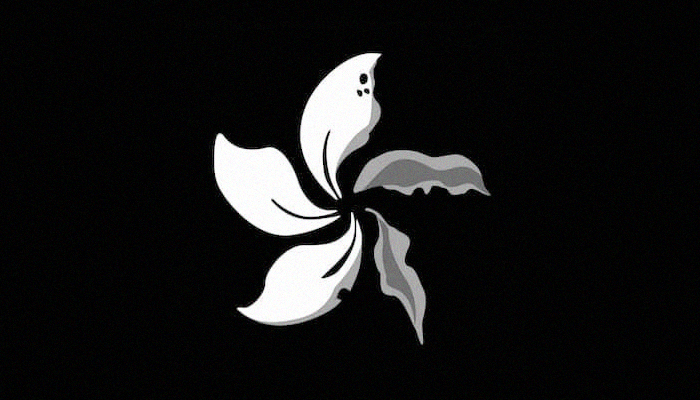

Anxieties have been symbolised in a profile picture that was being used by many opponents of the bill: a wilting depiction of Hong Kong's black-and-white bauhinia flower.

But protesters have become increasingly nervous that using the picture online could attract attention from authorities, and have taken it down.

"This reflects the terror Hong Kong citizens feel towards this government," said a woman surnamed Yau, 29, who works in education.

A protester surnamed Heung told AFP that many people immediately deleted "evidence showing you were present".

The demonstrators who spoke with AFP only provided their first or last names due to the subject's sensitivity, and all wore at least masks.

Heung, 27, had returned to the area where the protests had taken place to join the clean-up, and she put a post on Facebook calling for helpers. But she was afraid even a call for volunteers would link her to the protests.

"Maybe, I'll delete the post tonight," she said. "I don't want to become one of their suspects."

'It would become like Xinjiang'

While Hong Kongers have free speech and do not encounter the surveillance saturation on the mainland, sliding freedoms and a resurgent Beijing is fuelling anxieties and fears.

Recent prosecutions of protest leaders have also used video and digital data to help win convictions.

Bruce Lui, a senior journalism lecturer at Hong Kong Baptist University, said awareness around security has increased, particularly with China's "all-pervasive" surveillance technology and wide use of facial recognition and other tracking methods.

"In recent years, national security has become an urgent issue for Hong Kong relating to China. Hong Kong laws may have limitations, but China only needs to use national security to surpass (them)," he said.

The city was rattled in recent years by the disappearance of several booksellers who resurfaced in China facing charges — and the alleged rendition of billionaire businessman Xiao Jianhua in 2017.

Critics say the extradition law, if passed, would allow these cases to be carried out openly and legally.

"One month ago, things were still calm in Hong Kong," said Ben, the office worker.

"But in an instant, it has become this. Who knows if it would become like Xinjiang the day after tomorrow, because things can change so quickly," he added, referring to an autonomous region tightly ruled by Beijing.

In precarious times, many are holding onto core values.

"We're trying to do better with our privacy settings. But we still consider ourselves Hong Kong people, not Chinese, so we still think we have a right to speak out," said Yau.