What Karachi needs is autonomous city planning

The complex issue of Karachi’s urbanisation shows no signs of abating

September 22, 2019

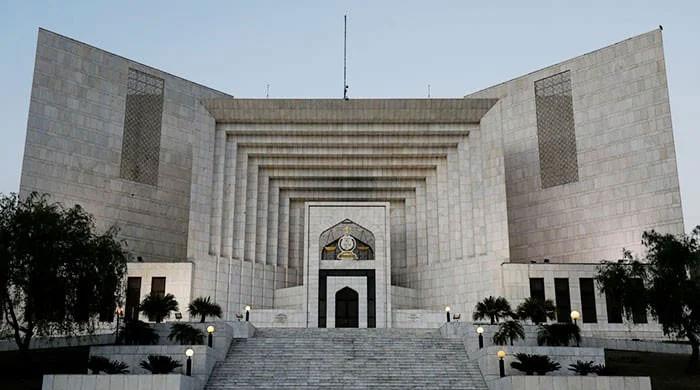

Federal Law Minister Farogh Naseem has put the cat among the pigeons. Earlier this month, he called on the Centre to assume administrative control of Karachi under Article 149 of the Constitution; to ensure better management.

Talk of ‘divorcing’ Sindh from its provincial capital has been presented as an empowerment initiative, as enshrined under Article 140A. The minister has already clarified that he sees no reason to restrict this proposal to Karachi alone. Thus other cities in Sindh, as well as those in Khyber Pakthunkhwa (KP), the Punjab and Balochistan could also ‘benefit’ from such out-of-the-box thinking. This has inevitably sparked debate about power-relations between Islamabad and the provinces. The speaker Sindh Assembly has rejected the proposal outright; emphasising that Article 149 (4) provides that the Centre can only advise — not take control of — the provinces.

While legal discourse gives way to political narrative, the complex issue of Karachi’s urbanisation shows no signs of abating. Population continues to be a concern. According to the provisional findings of the 2017 Census (which independent experts and institutions dispute as being too conservative in estimation), Sindh is home to some 47.89 million people; 52 percent of whom are urban dwellers. Karachi has a population of 16.5 million or one-third of the province’s total. It also has the second-highest growth rate among cities, next only to Islamabad. But essential services are running below capacity.

The Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) is among Karachi’s major infrastructure projects. The various routes — Green Line, Orange Line, Yellow Line and Red Line, which are at different stages of completion — will converge at Numaish before continuing along MA Jinnah Road. Thereby eventually displacing the historic retail and wholesale markets of Karachi South.

An autonomous city planning body is therefore imperative for Karachi. Far from being new suggestion, it was one of the key recommendations of two rounds of the Karachi Development Plans (KDP) in 1973-85 and 1986-2000; where draft laws for the consideration of provincial legislature were also prepared. It is time to revisit this. Not least, because the city is divided into multiple jurisdictions controlled by a patchwork of local, provincial and federal agencies, including the cantonments and military bases.

Development (or the lack thereof) in one locality directly impacts adjacent areas and beyond. Presently, responsibility for providing infrastructure and services is divided among several bodies. Thus establishing a unified vision and execution agenda remains paramount. This can never be realised unless and until the planning agency is administratively, technically and financially strong. It will also need to wield sufficient clout to enforce its writ over all institutions and stakeholders on the basis of technical merit and jurisdictional validity. In other words, the body must act as a filter; examining all investment proposals, project preparation and infrastructure development. Previously, the Master Plan and Environmental Control Department of Karachi Development Authority (KDA) managed all city planning. Then it merged with the City District Government Karachi (CDGK) and came to be known as the Master Plan Group of Offices. While KDA has been revived, its operational capability, especially in managing city planning functions, is limited. That being said, the Sindh government has already begun drafting a new law for urban and regional planning. An autonomous agency can steer Karachi towards technically sound and socially cohesive development and management options.

The last three planning attempts produced the two rounds of KDP as well as the Karachi Strategic Development Plan 2020. In objective and application, these had recognised the unique status of the city; as both a primate and a mega-city. It may also be noted that the earlier plans had tried to generate an exhaustive database, set of sectoral studies and analytical profiles. But any efforts on this front must take into account the inherent dynamism of the metropolis while achieving procedural outputs as per city management requirements.

Karachi has become a playground for real estate investors, largely due to the issue of unaccounted-for land. Most developed cities come up with strategies to address land allocation and implementation. After all, land, as a finite social asset, cannot be squandered. In Karachi’s case, this principle is grossly violated. Thus it is critical that GIS (Geographic Information Systems)-based land inventories are drawn up and that land assets held by various government agencies are publicly disclosed. This will help infuse transparency into transactions — leading to proper planning — while also helping to curb clandestine deals and allotments.

Pakistan’s largest city faces an emergency in terms of infrastructure provision, management and sustainability. It falls short on basic service delivery, including water supply, sewerage, stormwater drains, public transport, electricity and social amenities. All of which affects the common man. For instance, no decent public transport network exists. As a result, several thousand large buses, minibuses and coaches are ‘deployed’ to ease the staggering load of more than 20 million passenger trips. In most of the mega-cites, a mass transit system is created to shoulder this type of load. The BRT corridors are meant to offset this but will not be operational anytime soon. Additionally, many studies advocate the immediate revival of the Karachi Circular Railways (KCR) but to no tangible avail. It may be pointed out that in large cities, where commuting distances are extended and passenger volume is large, the feasibility of mass transit modes are ascertained at the earliest. Construction of flyovers and other localised projects are not likely to generate the same benefits as long-term remedial measures. An integrated transport system with multiple options for commuters is urgently required.

It is the citizenry that suffers in the absence of proper service standards and confusing procedures. Whether struggling to secure a water connection or building permit, the written procedures are, at best, terribly inadequate; at worst, they are non-existent. Public service counters and booths must be opened to increase the scale of service. Sectoral and area-wise performance must be studied over time in order to devise new systems. This is vital if the authorities are committed to improving the quality of life and the sphere of services for ordinary citizens.

Originally published in The News on Sunday