Battle of rights and ideas

In a country that does not prioritise education, yet simultaneously sets its hopes on the future dividends of a ‘youth bulge’, students are resisting becoming a wasted generation.

November 28, 2019

“The materialist doctrine concerning the changing of circumstances and upbringing forgets that circumstances are changed by men and that educator must himself be educated” (‘Theses on Feuerbach’, by Karl Marx)

Somewhere in ‘Mao Unrehearsed’, Chairman Mao observed that it is the youth that come up with radical new ideas, while old fogies generally resist change. This is happening here: across a barren landscape of stultifying universities that are otherwise churning out half-baked graduates. It is a battle of ideas and a struggle for fundamental rights.

In a country that does not prioritise education, yet simultaneously sets its hopes on the future dividends of a ‘youth bulge’, students are resisting becoming a wasted generation, and demanding their rightful place in an otherwise failed system, including the rights to question, exercise free speech and unionise. Like the continuation of General Zia’s ideological legacy and ‘Islamic provisions’, student unions remain banned for the last 35 years under a martial law order that could not be overturned, despite the ruling of a full house-committee of the Senate.

There is a lot of talk against the vices of a ‘class education system’, not only from the PTI government, but also from the religious right as well as the left. The PTI’s focus is on bridging the gap between English and Urdu-medium schools and establishing a uniform curriculum across a multi-cultural and multi-ethnic federation. Instead of giving greater priority to literacy, scientific education and diversity, the eclectic government wants to perhaps cobble together the ‘traditional’ and ‘modern’ sectors of the academia, while ignoring the class divide, regional disparities and ethno-cultural diversities. Rather than improving the public schools, they are regimenting the curricula of the public schools and thereby excluding critical thinking and research.

On the other hand, both the religious right and the left crave a ‘classless’ education system without, however, defining their objectives. The ideological position of the religious right revolves around an ‘Islamic education system’, and rejects secular education. However, they are not against the commodification of education and run many of the top chains of for-profit educational institutions.

Even if the Left’s position is consistently against the commercialisation of education, they have yet to embrace pluralism instead of their monist viewpoint and treat individuals as an “ensemble of the social relations” (Karl Marx). While fighting the hegemony of reactionary ideology, the Left should come up with an alternative secular and progressive worldview.

Much has been written about the prevailing formal education system, which has three broader variants. First, an imitation of The English Education Act of 1835 and the ‘Minute on Indian Education’ of Thomas Babington MaCauley, which emphasised modern education through the English medium and also has characteristics of the ‘Lead Nation’ theory, which says backward nations can develop in the footsteps of the lead nation (USA). Private English schools and top elite universities, though they follow the British pattern, essentially emulate the American system and cater to the requirements of the national and global corporate sector and elitist culture. Those produced by this elite sector are from the most privileged and serve a post-colonial elite.

Second, public-sector intermediary schools, colleges and universities are ideologically close to the Mohammadan Anglo-Oriental College founded by Sir Syed Ahmed Khan in 1875, which combined ‘modernity’ with ‘Islamic pragmatism’. This public education system performs the function of producing junior and middle tiers of government services and businesses. The emphasis is on seeking degrees rather than knowledge. They suppress critical thinking and creative approaches, and research remains a casualty.

And, third, the lower tiers of primary and secondary education and madressahs are the most neglected and backward – where poor quality teachers, if available, use coercive methods and medieval approaches to either suppress children’s curiosities or force them to drop out.

Worse than what is happening in our public and private education sectors is the plight of those unfortunate children who either have no access to any kind of literacy or are left at the mercy of local madressahs for ‘traditional’ grooming. In the absence of even minimal social succour, a vast majority of our burgeoning population suffers from poverty and deprivation.

They don’t have a present, nor a future in a most parasitic, underdeveloped, lopsidedly, exploitative and un-even social formation. They are coerced to live below the poverty-line or close to it and consumed as fodder for insecure, under-paid appalling wages of perpetual dehumanisation. Their stunted offspring, if they at all survive, are disposed of for child labour or are condemned to waste their childhood in the dungeons of orphanages/madressahs. At best, they learn by rote at outdated Dars-e-Nizamis to perform a variety of clerical functions or, at worst, become the foot soldiers of sprawling sectarian militias. Thanks to the obsession with English and Urdu as lingua franca, their mother tongues are not used as mediums of primary and secondary education, except in Sindh.

Those who can afford to send their kids to dust-gathering public schools with scant facilities, where pupils are coerced to memorize elementary skills without satisfying their inquisitiveness and realising their potential. The decaying public school system is not equipped with all that is necessary to explore the potential and boost the learning capacities of our children. Like millions of stunted children, their mental faculties are strained forever. If 24 million children are out of school, the highest dropouts are at the higher and secondary levels. Not only does the allocation for education remain stagnant at 2.4 percent of the GDP or even reduced, there is no effort to reform the governance of a stagnating education system and improve it qualitatively.

Instead of raising the allocation for education to the six percent of the GDP that is required to meet the requirements of youth bulge, the PTI government has sharply reduced the recurring grant by nine percent and Pakistan is going to miss the Millennium Development Goals, especially in the arena of quality primary and secondary education. Against the estimated requirement of universities to the tune of Rs149.743 billion in 2019-20, Rs71.75 billion is to be raised through higher fees and the government is dragging its feet to meet the gap. Similarly, Rs59,100 billion is allocated to Higher Education Commission against the minimum requirement of Rs 80,481 billion.

Above all, with 55 percent illiteracy among women and 30 percent among men, Pakistan has the lowest literacy rate in the region (57 percent), excluding Afghanistan. There are only 22 million students at the primary level, 2.8 million at the secondary level and 1.9 million at the post-secondary level with almost half (48.2 percent) of our girls out of the education system. Even those who have acquired various levels of education and certificates/degrees remain far below the average standards of knowledge, skills, intelligence and capacities commensurate with their respective levels.

The quality of our graduates is far inferiors to their counterparts in South Asia. The environment of our educational institutions is extremely conservative, suffocating, segregating and closed-minded and critical thinking, questioning and innovation is suppressed. Most importantly, education is divorced from practical life and requirements of employment. Standards are low and the examination system does not assess the qualities and capacities of students. Cramming, copying and cheating is the norm. Be it private or public, education has become a most lucrative money-making business.

Given this terrible state of education, students of various universities across the country are protesting and demanding wide-ranging reforms, including restoration of unions, free and quality education up to secondary education, higher allocation of resources for education (up to six percent of the GDP), opening up universities for free critical discourse, greater participation of girls, no sexual harassment, restoration of free environment and student unions and a guarantee for employment.

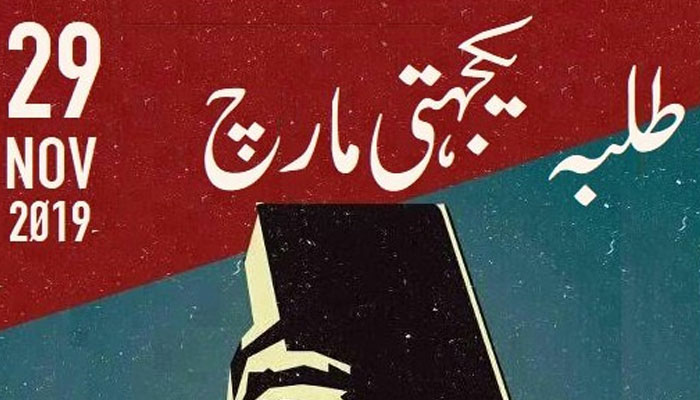

The Students’ March across the country on November 29 is the beginning. Students must assert their right to quality education, drastic reduction in fees and enhanced employment opportunities. Indeed, this is the beginning; catharsis must not be found just in slogans. This is a long struggle and patience is needed to integrate with the mass of our youth without alienating them with self-gratifying pseudo-radicalism.

The writer is a senior journalist.

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @ImtiazAlamSAFMA