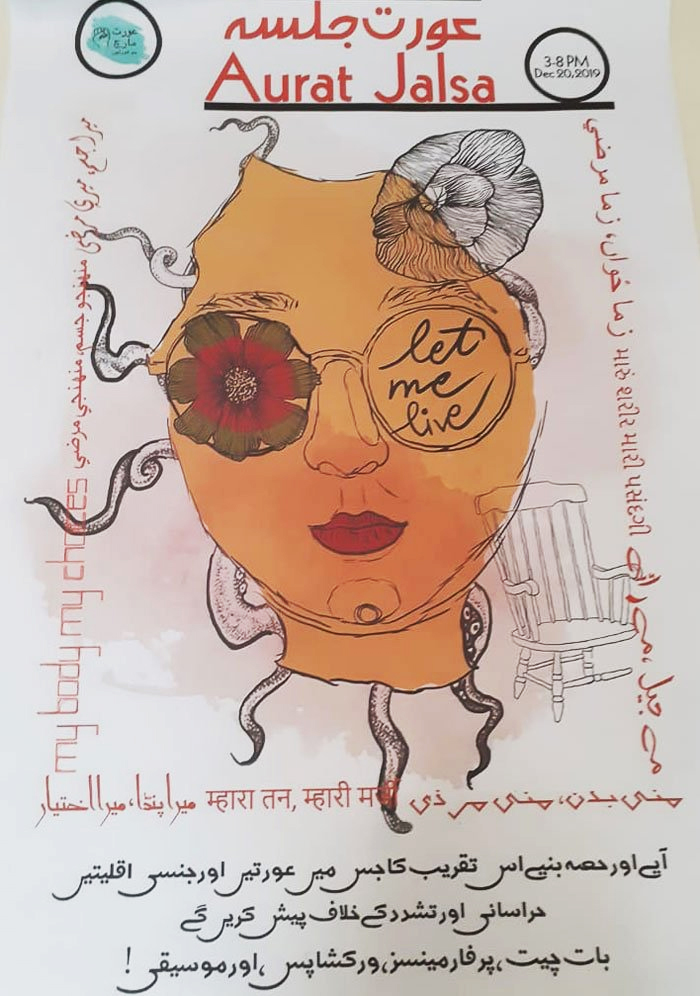

Aurat Jalsa 2019: Students demand end to pervasive surveillance in universities

The surveillance against a student was so intense that he had to resort to covering his face when appearing for his exams

December 21, 2019

"Your life is at risk within the premises of your own university," said a student at the much-anticipated Aurat Jalsa 2019 held Friday in Karachi's Arts Council.

Students in Pakistani universities are facing a major crisis — their safety. While the authorities attempt to silence and invalidate the experiences of sexual harassment and increased surveillance, students came together at the Aurat Jalsa — hosted by the organisers of the Aurat March — to talk about their experiences and the backlash they faced when trying to speak up and resist.

Titled "Harassment and Surveillance against Students," the session focused on raising awareness against the extensive surveillance and spying students are subjected to on a daily basis in both private and public institutions, as well as measures to address such problems.

The session revolved around the accounts of discrimination and harassment from students — including women, as well as gender and sexual minorities — in major public and private universities.

“The aim of these discussions is to essentially get people who are experiencing the same kind of injustices in a room and figure out how to address them because the student populace of this country is facing a crisis right now,” said one of the moderators of the discussion.

“There are horror stories emerging from all corners the country, even across the border," she said.

The talk began with different students speaking about the kind of harassment they have faced and how the universities' administration and authorities addressed such incidents. In addition, the conversation also included the kind of surveillance tools that are being used by heads of security.

A recent 'surveillance camera scandal' in Balochistan University — in which administration officials were found to have used surveillance videos to blackmail students — had prompted a discussion on the violation of basic rights and the use of surveillance as a tool of harassment. Students from universities across the country had consequently demanded a fair and just inquiry into the allegedly questionable behaviour of the officials.

Interestingly, however, the incident had led to security personnel being deployed at the university and the governor secretariat ordering the varsity's chancellor to "stop all political activities".

A student, who was in attendance at the Aurat Jalsa, pointed out that there was no privacy for both male and female students — to the extent that there are cameras installed even in the bathrooms.

There was harassment at both collective and individual levels as many female students were discouraged and made to leave the university, he said, adding that when such incidents were addressed, the university responded by trying to shut down the cases as early as possible.

Even in relatively progressive private universities, the case was not much different. As pointed out by another student, talks were limited to academics and classrooms despite the institution claiming to be progressive in nature, she said.

The student added that her peers were seen as commodities, as “business transactions”, rather than autonomous individuals.

The panellists further underscored how every time someone was subjected to any kind of harassment or sexual misconduct, most universities' first response was to shut it down and sweep it under the rug.

Security officials at the universities, as well as the management, were usually aware of all activity that happened on campus owing to cameras almost everywhere on the premises, the students said. There was no proper long-term solution provided, they lamented, and if there was a student-led committee that dealt with such incidents, it, too, was also dissolved.

Another public university student highlighted that people who travelled from rural areas to larger cities for education were discriminated against based on class and gender, and, therefore, became demotivated. Those who had courage to speak up, on the other hand, were also intimidated by teachers and authorities in terms of academic penalisation or threats of suspension and expulsion.

“Your marks are in my hands,” said a teacher, according to a student when they had resisted.

To emphasise how deep the surveillance went, a student claimed that his university administration went to the extent of tapping his phone when he attempted to speak up on issues frequently. Not only were his location and social media tracked, the student alleged, the management also pressurised his family and friends by saying they had power over them due to the information they had access to.

Other forms of threats from universities' administrations included intimidation through the help of security personnel, cancelling admissions, and, according to one student protester, distancing themselves from responsibility.

“You’re responsible for your own safety,” the student narrated, quoting university officials from a past incident. The surveillance was so intense that he had to resort to covering his face even when appearing for his exams to hide from right-wing groups.

“Your life is at risk within the premises of your own university,” he stated.

In an attempt to counter the problem of alleged harassment, the universities’ idea of a solution was to install more cameras, consequently giving rise to the issue of increased surveillance.

After sharing her experience of harassment, a student stated that in most cases, there was no accountability, especially against the people in higher positions. Even if one tried to speak up, “they can’t [speak] against people in higher posts since they’re the ones in charge” of giving a verdict.

Institutions also delayed the process in on-campus sexual harassment cases, the students added, and required “proof” from victims, either in the form of evidence or witnesses. They underlined that it was almost impossible to produce proof because no one recorded themselves round the clock and perpetrators make use of strategic placement of surveillance cameras.

In addition, those in charge also discouraged students from reporting sexual harassment by questioning the validity of the survivors' claims and bringing in extraneous variables like the aggressor’s past behaviour and personal dealings, vouching for their character, and invalidating the experience by questioning why the incident was brought up after a long time.

Speaking to Geo.tv, one of the moderators stressed on the need for student unions and why the discussion at the Aurat Jalsa was important as it concerned the safety and growth of the country's youth, who form a large portion of the population.

“Given the sort of political climate we are in right now, even the Sindh government has recognised the need for student unions. University spaces are not safe right now. If a space is hostile — which they are — it is not a conducive environment for learning,” she added.

“This depoliticisation of students and students' activity is extremely dangerous as it has shown us that when students are discouraged from politics, politics as a whole suffers. That is the problem.”

The feminist added that everything in the agenda was important since it is the right of the students, as Pakistani citizens, to have complete transparency when it came to their university's policies. She also spoke of how these discussions were a way to talk about the students' issues at their core and find a way to cope up with them and come up with peaceful ways to resist.

"We are reclaiming our rights to these places since we are the major stakeholders,” she said. “The university exists because of us. And as students, it is our right to have a say, to have transparency to all the policies that are being made in any department.”

Towards the end of the session, the students demanded that universities set up sexual harassment committees and devise proper procedures to entertain the complaints. A professor — who was also part of the panel — shed light on how such instances of surveillance by authorities was part of a larger issue, which is bigger than the institutions themselves. Such institutions then become sites of power since students are forced into silence.