What is Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine?

US has recorded more than 14,000 cases of new coronavirus infection, 205 of them fatal

March 20, 2020

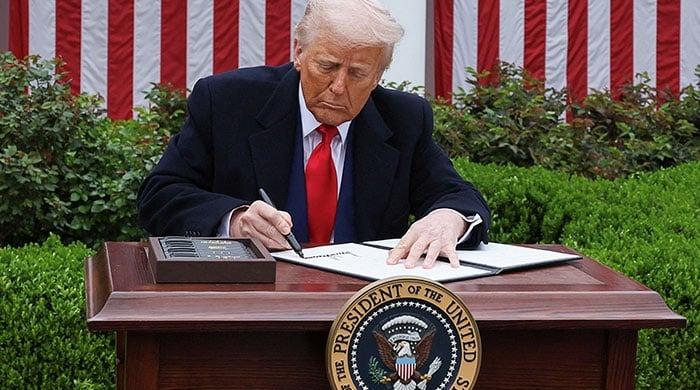

Washington: The US is fast-tracking antimalarial drugs for use as a treatment against the new coronavirus, President Donald Trump said Thursday, following encouraging early results in France and China.

Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine have not been given a formal green light in the US to fight the pandemic, but the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) said it would work with domestic makers to expand production as it studied their efficacy.

The news came as Senate Republicans unveiled a $1 trillion emergency relief package to combat the economic turmoil caused by the virus -- which must now be examined by so-far skeptical Democrats, who want to include direct financial aid to individuals, before a date can be set for a vote.

The two drugs mentioned Thursday are already approved for malaria, lupus and rheumatoid arthritis, and doctors in the US may prescribe any drug they believe is appropriate medically.

"We´re going to be able to make that drug available almost immediately, and that´s where the FDA has been so great," Trump told reporters, referring to both compounds.

The US has recorded more than 14,000 cases of new coronavirus infection, 205 of them fatal, according to a Johns Hopkins University tracker. But authorities expect the number to rise steeply in the coming days because of increased levels of testing after initial delays.

"If there is an experimental drug that is potentially available, a doctor could ask for that drug to be used in a patient. We have criteria for that and very speedy approval for that," said FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn.

"As an example, many Americans have read studies and heard media reports about this drug chloroquine, which is an anti-malarial drug.

"That´s a drug that the president directed us to take a closer look at, as to whether an expanded use approach to that could be done to actually see if that benefits patients."

Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine are synthetic forms of quinine, which is found in the barks of cinchona trees of Latin America and has been used to treat malaria for centuries.

Some in the wider scientific community have cautioned more research is needed to prove that they really work and are safe for COVID-19.

But French drug maker Sanofi said on Wednesday it was ready to offer the French government millions of doses of hydroxychloroquine, sold under its brand name Plaquenil, in light of a "promising" study carried out by scientist Didier Raoult of the IHU Mediterranee Infection in Marseille.

Raoult reported this week that after treating 24 patients for six days with Plaquenil, the virus had disappeared in all but a quarter of them.

The research has not yet been peer reviewed or published, and Raoult had come under fire by some scientists and officials in his native France for potentially raising false hopes.

"I´m just doing my duty, and I am happy to see that now eight or nine countries recommend chloroquine treatment for patients with this new coronavirus," he told AFP.

- Encouraging -

Several clinical trials are also underway in China, where authorities have announced positive results but not yet published their data.

Karine Le Roch, a professor of cell biology at the University of California, Riverside told AFP she was encouraged by recent work in France and China.

"I will say there is a very small number of patients, but if the results are correct, it seems to indeed decrease the viral loads of infected patients," she said.

"It´s encouraging but we have to make sure the results are accurate and then confirm that with a larger number of patients."

Scientists understand how these alkaloid compounds work at the cellular level to fight malaria parasites -- but it´s not yet known how they are fighting the coronavirus, Le Roch added.

"It´s highly possible that this compound is changing the acidity of the cells infected with the virus," she told AFP.

"And then the enzymes that are needed for the virus to replicate cannot work as efficiently as they would work without the drug."

But not everyone is convinced.

Writing in the journal Antiviral Research, French scientists Franck Touret and Xavierde de Lamballerie urged caution, noting that chloroquine had been proposed several times for the treatment of acute viral diseases in humans without success, including HIV.

They added that finding the right dose was crucial because "chloroquine poisoning has been associated with cardiovascular disorders that can be life-threatening."