A widow in Balochistan waits for help during the lockdown

Bibi Jan, a 65-year-old widow is among hundreds of people left to fend for themselves due to the coronavirus lockdown in the province

April 07, 2020

Bibi Jan is a 65-year-old widow. Until two weeks ago, she worked as a housemaid for a family in an upscale neighbourhood of Quetta in Balochistan. Then one day the family packed up and left, as coronavirus cases spiked in the city.

Bibi knocked on a few doors in the area looking for work, but few seemed interested. On March 24, the Balochistan government announced a 15-day lockdown across the province, to contain the numbers of people being infected with the deadly virus.

There was no prior warning and no time for preparation. Quetta and its surrounding areas shut down within 24 hours, leaving hundreds of people like Bibi to fend for themselves.

Bibi lives with her three minor granddaughters, who she takes care of after her daughter died last year. She has no source of income and there is no man in the house either to offer help.

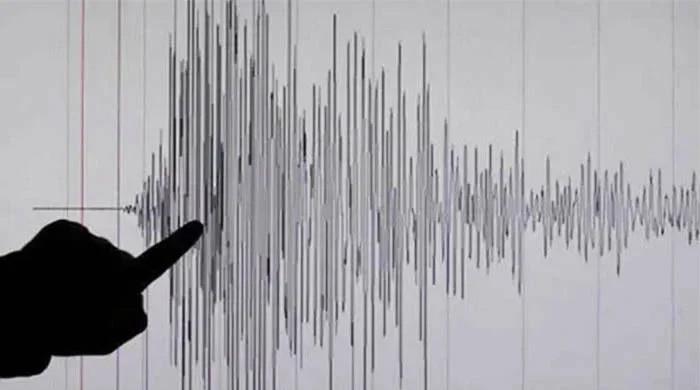

Balochistan has a total of 202 recorded cases of coronavirus, as of April 7.

Read also: Students and teachers at crossroads over online education in Pakistan

While the provincial government has decided to slashed taxes worth Rs1.484 billion to help citizens cope with the impacts of COVID-19, it is unclear what kind of help will it offer people like Bibi, who are desperate for assistance.

The federal government, Punjab, Sindh and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa has all announced separate relief packages for the daily wagers and others below the poverty line. While Balochistan’s chief minister has promised to distribute rations amongst the daily wagers.

But Bibi is still waiting for help. “Where is the [financial] package?” she asks, sitting at her home, “When will they give us some money to feed our children?”

To further compound the issue, as soon as the lockdown was announced, the prices of essential commodities shot up in all 33 districts of the province.

In Quetta, there was a 50% increase in the prices of edible goods and fruit and the local administration did nothing to control the profiteering.

The lockdown has so far forced a large number of labourers and hourly wage workers to leave the cities and move back to their homes in the rural areas. Others can be seen openly defying the lockdown. One labourer I spoke to said, “The virus doesn’t worry me much, but the uncertainty of when I will find work does.”

As for Bibi Jan, there is no saying how long she will have to wait for help to arrive.