Stray musings: why did ordinary Pakistanis turn into a gouging mob? (Part II)

How is the closing of the Pakistani mind to be reversed?

September 04, 2021

In the decade or so after school as I negotiated various economics and law degrees at Cambridge, London and Harvard, I kept returning to Pakistan and the conversations that were happening across the land throughout the Zia years and beyond.

Not that the universities were barren spaces in the Thatcher-Reagan years. That is a story for another time. There was Sarmad Sehbai’s Sangat Shah Hussain in Islamabad. Maharaj Kathak was around, still dancing and regaling us with tales of his time with Agha Hashr and the Parsi Theatre in Calcutta. Ahmed Faraz would drop by once in a while. There was music. Incessant. Ahmed Zoey was smoking away and painting wood goddesses in his studio-bedroom at Sehbai’s home. People turned up with their poems and short stories. These were read out and critiqued. Then we would read Manto. The evenings ended with Eliot. Those were heady days. Our world was no wasteland. ‘Kuch ishq kya, Kuch kaam kya’.

In time, I got to behold the great English language poet Taufiq Rafat. The Arabic department at the National Institute of Modern Languages at which I was enrolled by way of daytime activity for a year was a serious place. As was the Khana-e-Farhang-e-Iran. Five levels of Persian learning at the Khana still left me short of what Master Dina Nath had imparted to my father.

One day the son of my father’s closest friend from his days at prime minister Liaquat Ali’s office turned up. He had discovered an exciting new scholar called Javed Ghamidi from Pakpattan. I went along. This was before Ghamidi Sahib was the presence he is now on electronic and social media spaces. This was also before the murderous attacks that killed his associates and led to Ghamidi Sahib leaving Pakistan. His Model Town Lahore Centre, Al Mowarid, became the place to be. Quranic hermeneutics and a dissection, altogether different from Pervaiz Sahib’s, of Dr Israr and Maudoodi Sahib’s politicization of Islam were the activities to undertake. Ghamidi Sahib would read out from the tafsir he was writing at the time. His Urdu had a soothing quality. Pervaiz Sahib’s was grand, bordering on the grandiose. While Ghamidi Sahib appeared more firmly grounded to me, they had both in their differing ways come to see the traditional ulema as having lost feel for the creative possibilities of life. They had become guardians of ossified texts of jurisprudence. In bemoaning the lot of the would-be devout practitioner, Pervaiz Sahib drew inspiration from Iqbal: ‘Reh gaye sufi o mullah ke ghulam ae saqi!’

Marriage through Wasif Sahib’s ‘khirqa’ to a graduate of, and later teacher at, the National College of Arts brought into our home much of the arts scene of Lahore. Quddus Mirza with his concern for the quality of the brush stroke. Rana Rashid experimenting with new media collages. Imran Qureshi and Ayesha Khalid were clearly special. Madam Shabnam was relentlessly pursuing learning and was to reach a PhD at Harvard well into her fifties. Nayyar Ali Dada’s Nairang Gallery became a shade away from a society that seemed to have exhausted itself. Habib Jalib had become a friend. As he lay dying alone in Services Hospital, he held my hand, “They will hold grand functions when I am gone”.

At the Nairang Gallery Intizar, Husain Sahib would walk by with Masood Ashar Sahib. Nayyar Sahib had asked me a few times to join their monthly sessions when the ‘greats’ would meet to discuss art, music and literature. I could never quite summon the courage to sit with them. Years later, I had the privilege to work with Masood Ashar Sahib on the board of Mashal, an organisation devoted to translating important texts into Urdu. Ashar Sahib has now followed Intizar Sahib into immortality.

The legal profession had its own founts of learning. I first met I A Rehman Sahib in London as a student in the late 1980s through Professor Amin Mughal, the reformed Stalinist (his own self-description in jest) ‘murshid’ who continues to bless so many students from Pakistan on their way to their individual dreams. Rehman Sahib was the soul and the guiding beacon of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan. The votive force of the Commission was of course Asma Jahangir.

The first case Asma asked me to assist her in was about a Muslim woman’s capacity to marry out of her own will without a male guardian’s consent. With that I was on my way. There could not be a turning away. There was so much to learn and fight off. During the Musharraf Emergency when I was arrested, along with Asma and so many others from the offices of the Human Rights Commission, we laughed and sang all the way to the Model Town police station. There was no fear. We were still full of hope. I had earlier been thrashed, cane sticks on the head with sterner stuff for the body, on the Mall Road by the police. A fractured hand led to a change in my signature that continues to remind me of that day.

Years later, I was sitting with then opposition politician Imran Khan. One of his sisters, a remarkable woman devoted to the hospital and the university established by her brother, was also present. I had by then handled the NRO Case for Dr Mobashir Hasan and the eponymous Asghar Khan Case for the remarkable air marshal about interference by the agencies in the electoral process. Imran Khan Sahib had come to rely on me for a growing portfolio of legal squabbles he and his party faced. He asked me suddenly, “What is the one thing you would like me to do if I become prime minister?” My immediate response, decades in the making, was: “No one should feel defeated by an alien language, and no one should be denied the knowledge that exists in that alien language. Make teaching English a national priority but also translate everything. Create the next Bait al Hikmah. Let all knowledge flow regardless of origin or ideology. Let there be debate and dissent. Let the formative years of a child be years of creative expression. Of songs and colour.” Khan Sahib looked back, slightly surprised. “Is that the first priority? Ok, noted”. He almost smiled.

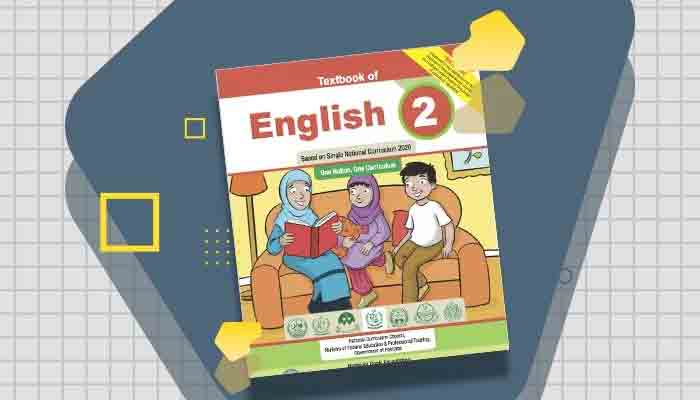

In the personal depression that followed the Minar incident, one looked for hope. How do we set about nourishing the mind and the soul? How will we enable dissent in words, beliefs and lifestyles to be embraced? How is the closing of the Pakistani mind to be reversed? I remembered my conversation with Imran Khan Sahib and went over to obtain a complete set of the Single National Curriculum textbooks that had just been issued for classes 1 to 5. As I leafed through the pages I was struck by an illustration of a young girl, no more than five years old, playing with her doll and a teddy bear at home. The young child was in hijab, her hair securely covered and an abaya-like covering across her torso. The teddy and the doll were not in hijab.

A tour through all the textbooks, regardless of subject, confirmed the overwhelming norm of the ‘good woman/child’ that the books seek to affirm. The woman at Minar-e-Pakistan failed that norm. So would have my mother and the women I grew up with. As will my daughters. Each plays an instrument. They sing.

I turned to the curriculum statement looking for the music and art content. Nothing came up. I then discovered that the Punjab Curriculum and Textbook Board is required, since 2020, to have all its publications and approved textbooks vetted by the Muttahida Ulema Board. I called friends who are engaged with the national curriculum effort. Why were they not protesting? They sounded sheepish.

I have indeed gone all wrong as my friends tell me. It is time to join the flow. To use access and privilege. Appear pious. All fractured psyches are to be banished. All are to think alike. My father’s dear friend Mustafa Zaidi calls out from afar. ‘Ek hi rah puhnchati thi tajjali ke huzoor, hum ne uss rah se munh mora hai – hum jantay hain’.

Concluded

Originally published in The News