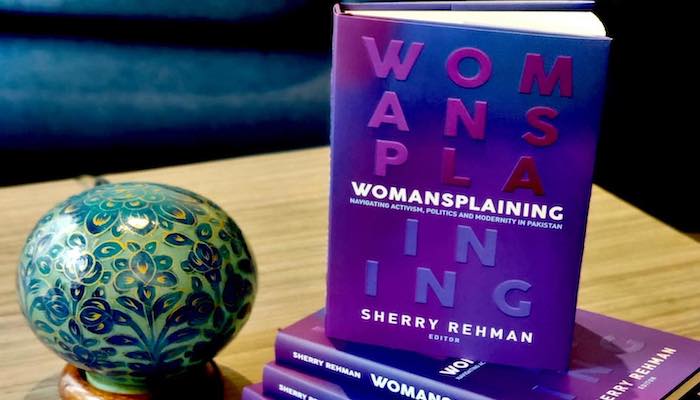

Women who write about women

‘Womansplaining’ is a collection of essays by and about women who struggled and inspired, women who suffered, women who liberated others from their sufferings

September 14, 2021

Womansplaining, edited by Senator Sherry Rehman, is an anthology of thought-provoking essays – written by some of the most remarkable women – ‘navigating activism, politics and modernity in Pakistan’

The essays are by and about pioneering women, women who struggled and inspired, women who suffered, women who liberated others from their sufferings. There are women who dreamt big and surmounted impossible challenges. There are women who had to put up with serious consequences for standing up and speaking up. There are women who lost their fight. There are women who waged wars on various fronts for their rights and left behind legacies of feminine valor.

This book has a number of enchanting snippets from the life histories of Pakistan’s daring women whose commanding voices have had far-reaching impacts. Apart from stories of valor there are philosophical debates about the women’s rights movement, including its epistemological foundations, semantic overtones and taxonomy.

There are some sobering facts in it too, and some inspiring life stories of women constantly overcoming institutional obstacles and negotiating with patriarchal structures.

The anthology makes the reader walk through various phases of the Women’s Action Forum (WAF), which mainly began in the early 1980s in opposition to the draconian laws imposed by the dictatorial regime of General Zia. It is amazing to know the way a few brave women weathered those storms and created a platform which was to provide a solid reference point for various ‘dispersed feminisms’.

If you are a millennial feminist activist, you may want to read through at least the first few essays. Farida Shaheed’s essay titled ‘The Women’s Movement in Pakistan: Anatomy of Resistance’ and ‘The Politics of Activism: Bridging the Generational Arc’ written by Ayesha Khan are particularly interesting.

These essays map the emergence and transformation of WAF, the principles it was founded on, and the ideology it espoused. For those entering the feminist activism scene after 2000, these essays chart out a clear perspective to anchor their struggles in.

If you are a history buff, you may want to read this book for a brief introduction with some of the distinguished women, their struggles and achievements before the formation of WAF. Khawar Mumtaz’s essay titled ‘Skin in The Game: From Activism to Politics’ is particularly mesmerising, as she tells us that in the Subcontinent women have agitated for the right to education in 1903, for inheritance, against polygamy and for equal franchise in 1917. They have created organisations to promote the status of women as far back as 1908.

Sherry Rehman, in her essay ‘The Parliament percentage: Token or substance’, charts how women have used legislation and the contested politics of affirmative action to both disrupt and ‘actionalise’ social norms that define who uses power and for what ends. Rehman convincingly argues for strengthening linkages between younger feminists, older activist leaders and parliamentarians ‘to re-bond as allies in reform’.

If you are a Marxist feminist, reading Afia Shehrbano Zia’s essay titled ‘Contesting the Class Question: Moving beyond Piety and Patriarchy’ is likely to interest you. Zia raises some interesting questions about the role of the state, military rule and Islam. She poignantly observes: “why is there such little work on the gendered impact of the political economy? Why is there no substantive academic thesis, study or organization around women’s market activities, labour laws, agricultural and domestic workers, or any mapping of women workers in the informal sector?”

In a similar vein, Zeenia Shaukat’s essay titled ‘Women Workers: Bargaining Basic Rights From The Margins’ highlights the poor working conditions for women in Pakistan, which are defined by four important factors: “low wages; minimal labour protection due to poor legislation for the urban economy, with no legislation in the agriculture sector; poor implementation of existing legislation that may have provided limited protections; and limited access to remedial measures, including judicial recourse”.

If you are a lawyer, reading essays written by Hina Jilani, Sara Malkani, Maliha Zia and Sarah Belal could be of great help in understanding law as an instrument of change and how one could push the limits of laws. As Maliha Zia notes in her essay, “when the Zina Ordinance was finally amended through the Protection of Women (Criminal Law Amendment) Act of 2006, there was an instant impact on women.”

Hina Jilani, whose engagement with human rights in Pakistan began in 1979, in her essay titled ‘The Fight For Human Rights: A View From The Trenches’ writes that “one of the major realities we have come to understand is that improving access to justice is ultimately a political process and no strategy will succeed if it ignores this fact.”

If you are an actor or drama lover reading ‘High Drama: Retrogressive Fictions and Pakistani Soaps’ written by Fifi Haroon is a must read. Haroon writes: “Unfortunately, the drama serials of the last ten years have mostly reinforced conservative notions of female morality and extolled suffering within the family context as virtuous.” She concludes that Pakistani dramas mostly “pitch women against one another rather than telling stories of female solidarity”.

Read Sharmeen Obaid’s essay titled ‘Let Girls Dream: Stories From The Edge’ to know in detail how Gul-e-Khandana of Swat is teaching young girls to think for themselves and about Tabassum Adnan who after escaping the nightmare of early marriage, formed Khwendo Jirga in 2013.

If you are a development activist Ammara Durrani’s essay titled ‘Navigating Development: Wins, Deterrents And New Ambitions’ will make an interesting read in which she proposes to re-politicise development for equal power. For Durrani, it is worrisome to think of such little impact all these feminisms have had in shifting the gender balance of power. She ends her piece by raising some pertinent questions making a case for ‘rewriting the narrative’ and setting ‘a new indigenous agenda’ for women activists.

Rimmel Mohydin’s essay ‘Field Notes from the Aurat March: The Millennial Megaphone’ would tell you why millennials had to resort to an Aurat March. If you are offended by Aurat March placards or are a misogynist, I suggest you read all 22 essays to cut your inflated male ego to size.

I would highly recommend this book if you want to understand why we will not be able to achieve sustainable development goals without gendered policies and practices. Shahnaz Wazir Ali’s essay on public health, Ayesha Razzaque on girls’ education, and Zofeen Ebrahim on climate change are a must-read in this context.

Credit goes to the editor for compiling these inspirational writings of all these excellent minds in a single volume: a job well done indeed.

The writer heads the Sustainable Development Policy Institute and tweets @abidsuleri

Originally published in The News