As fake vaccine certificates proliferate, Pakistan moves to secure COVID vaccination drive

Authorities are putting in place measures to safeguard national COVID-19 vaccination drive against fraud by unscrupulous players

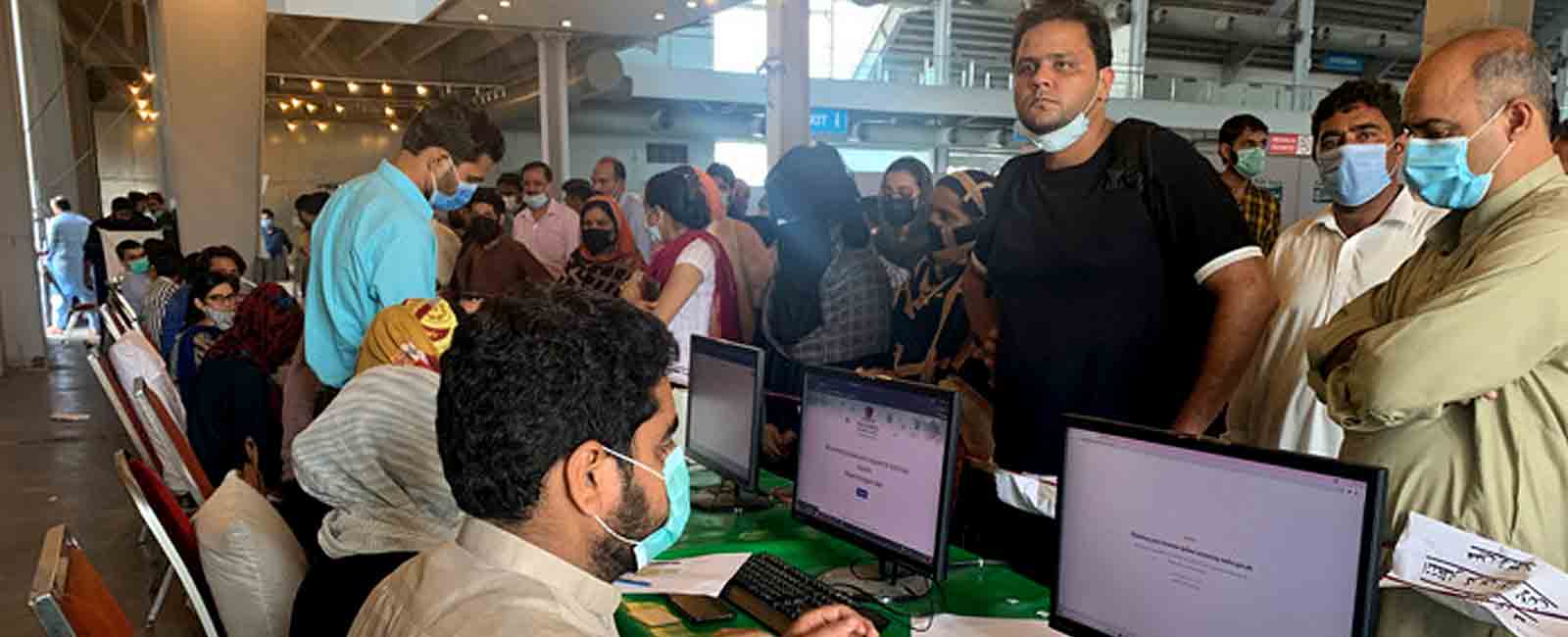

Last month, Saqib Baig, a worker at the Health Department in Pakistan’s eastern city of Lahore, was given a special assignment – catch people trying to scam Pakistan’s coronavirus vaccination drive.

Overnight, Baig was posted at the Expo Center, one of the largest vaccination centers in Punjab.

These days, Baig, along with seven other men and women, spends an eight-hour shift scanning people’s documents and keeping an eye out for those trying to defraud the system.

In particular, Baig is on the lookout for people who come to the center, get themselves registered at the counter for a COVID shot, but then leave without actually getting the vaccine.

It’s a simple way to defraud the system: once a person is registered at the vaccination center, their details are uploaded to a national database and their status is updated as ‘vaccinated’. Once registered, people are expected to wait till they are called in for their shot — but some shifty players have figured out that by leaving right after registering themselves, they can retain their ‘vaccinated’ status without actually receiving a dose.

These people can later enter their personal details on the National Immunisation Management System’s (NIMS) online portal and obtain a vaccination certificate, which can then be used to get around COVID restrictions.

“Just yesterday, I caught around 70-80 people trying to leave the center without receiving a dose,” Baig tells Geo.tv during a conversation in the brightly lit hall of the Expo Center.

“They come up with the funniest excuses too — ‘oh, I have a rare health condition, so I can’t get a vaccine’,” he adds, chuckling.

People try to evade Baig and his colleagues by pretending to step outside to receive a phone call, or hide in washrooms and try to slip out later, Touqeer Anwar, the supervisor and Baig’s boss, tells us.

“Once we catch them, we try to reason with these people and convince them to get a vaccine shot. If they don’t agree, we have to call the police,” Anwar adds.

It bears mentioning at this point that people obtaining fake and fraudulent certificates are in no way a problem that is specific to Pakistan.

Around the world, vaccine deniers (anti-vaxxers as they are called) are finding new ways to defraud vaccination systems, including in the US and Europe, and the issue has been extensively reported in foreign media. It is a persistent headache for health authorities around the world as they try to ward off the pandemic.

Vaccine mandates create demand

In recent months, the Pakistan government has made it increasingly difficult for unvaccinated people to travel; to enter restaurants, shopping malls or educational institutes; and even to purchase petrol for their cars.

This has prompted a rush of people looking to obtain fake vaccination certificates to avoid these restrictions — and, with time, people have found new and creative ways to get a fake or fraudulently obtained vaccine card.

However, the issue is now turning into a political tussle and getting national attention.

On September 23, misinformation was fed into the government’s online portal under the name of Nawaz Sharif, former prime minister and supreme leader of the PML-N.

Sharif has been residing in London since November 2019, but the data showed that he had ‘received’ both his vaccine doses in Pakistan last month.

According to the police, the entry was made by two government employees in Lahore who had access to the national vaccine management system’s database.

Then, on October 5, a similar attempt was made — this time from Narowal. Using Sharif’s name and National Identity Card number, two health employees once again attempted to generate a vaccination certificate for the former prime minister. On the same day, two more fake entries were made from Multan and Vehari in the name of Sharif’s late wife, Kulsoom Nawaz, and his former finance minister, Ishaq Dar, who is also currently in London.

Speaking about the initial incident, Anwar, the supervisor at Lahore’s Expo Center, described it as “just [a] political [stunt] and nothing else” — aimed at damaging the credibility of the vaccination system set up by the ruling Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf, a rival of Sharif’s PML-N.

When approached, Imran Sikander — secretary of Punjab’s Primary and Secondary Healthcare Department — refused to talk about the Sharif case, describing it as a “sensitive issue” which is currently in the FIA’s purview. He did admit, however, that fake entries in the vaccination management system have emerged as a problem over the last two months.

Health officials and persons associated with the health department were found involved in the majority of cases of vaccine fraud, he said.

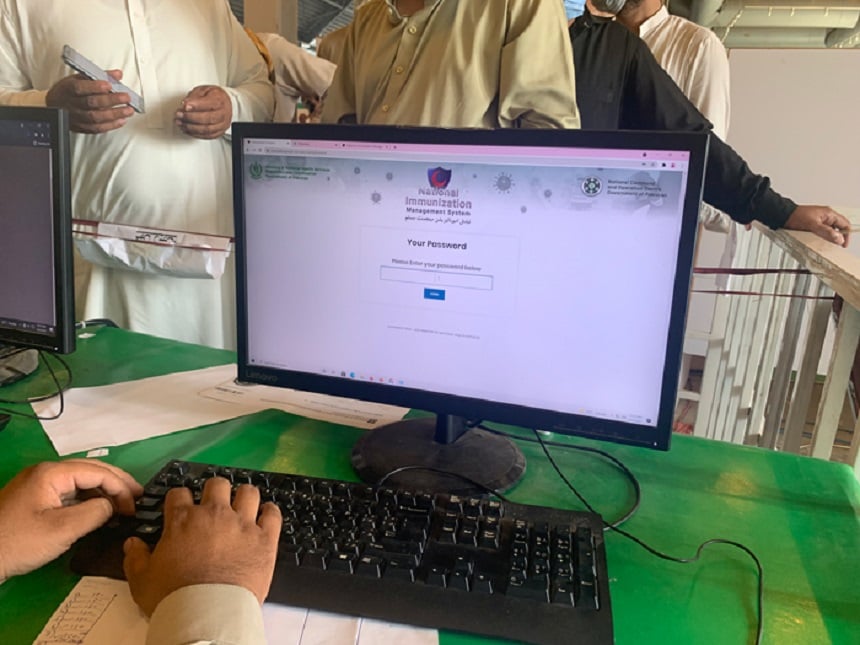

Health officials have access to the NIMS database so they can update the vaccination status of citizens in the national register. Some unscrupulous officials sought to take advantage of these privileges by getting “involved with touts from the general public to enter fake data,” reads a report by the Primary and Secondary Healthcare Department.

To date, in Punjab alone, 79 people are facing departmental inquiries, 12 police complaints have been launched and 16 people have been arrested, the report states.

But Sikander argues that the issue of fake vaccine certificates is not as prevalent as is being reported in the media.

“Since February, Punjab has administered 46 million doses of the coronavirus vaccine, of which we found 9,717 entries (0.02%) to be faked. That is a small percentage,” he says.

The scam is not exclusive to Punjab either: at least 5,000 fake COVID-19 vaccine certificates have also been detected in Sindh, a senior health official from the province, who chose to remain anonymous, told Geo.tv.

Those involved, in almost all cases, were data operators hired from the private sector at vaccination centers; tasked with making entries to the vaccination database. To date, inquiries have been launched against 40 such operators.

“Some health workers started this practice,” the Sindh official told Geo.tv. “These health workers were scared of getting vaccinated, so they bribed the data entry operators to show that they had received both doses of the vaccine. Later, these operators offered their ‘services’ to the general public in exchange for cash.”

Qasim Soomro, the parliamentary secretary of Sindh, said around 12 criminal cases have been registered in Sindh, and records of hundreds of people who were fraudulently issued vaccine cards have been sent for cancellation to the National Command and Operation Center (NCOC) — the apex body working on pandemic management in Pakistan.

“If somebody has information regarding individuals who are still involved in issuance of fake vaccination certificates, they should come forward and help us,” Soomro urged.

Dr Faisal Sultan, special assistant to the prime minister on health and the senior-most health official in the country, told Geo.tv that when the NCOC receives information about a fraudulent certificate, the certificate is immediately revoked.

However, he too underlined that though vaccine fraud cannot be denied, it is not as ‘common’ as some people believe it to be.

“Given that Pakistan has administered 80 million doses so far, it is a very rare problem, but, yes, it does exist,” he told Geo.tv.

Nonetheless, even if they say instances of vaccine fraud are rare, authorities are taking the scammers very seriously.

In order to stop criminals in their tracks, the government has rolled out three broad measures to try and limit unscrupulous activity.

One, they have posted watchmen, like Baig, at vaccine centers to keep a lookout for people bypassing the system.

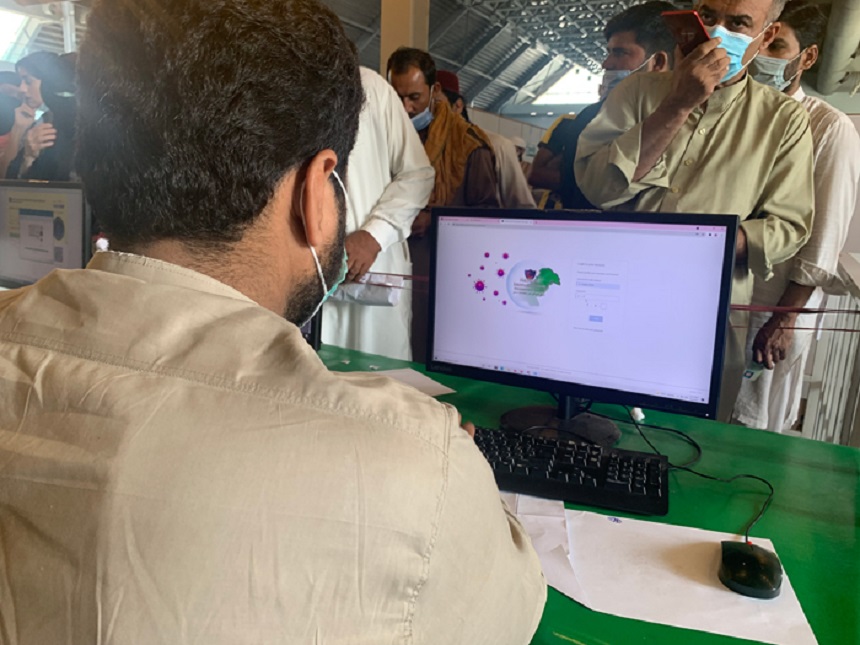

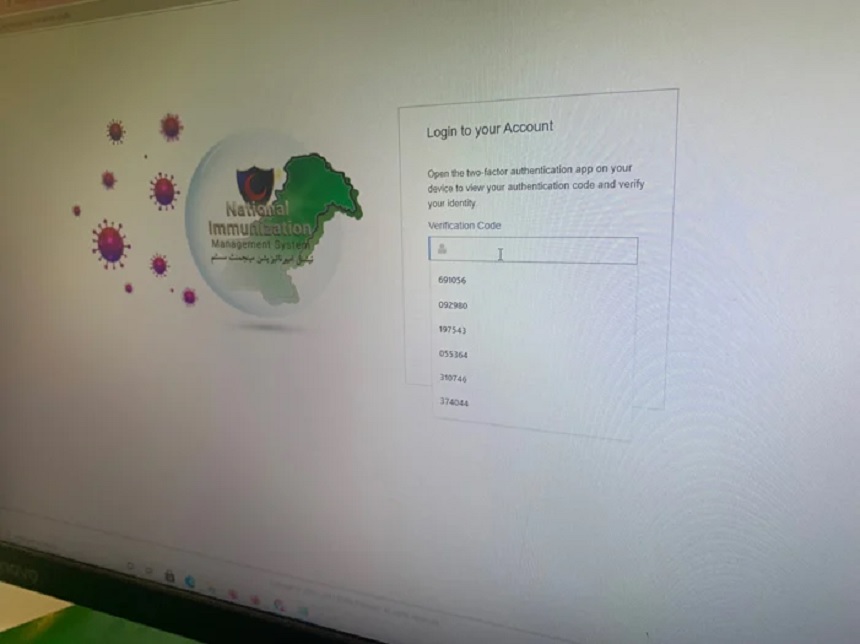

Two, they have launched a two-factor authentication system for people logging in to the national vaccine database. This means that when a data operator or health worker logs in to the system, they receive an authentication code on their phones which they have to verify before they can proceed. This ensures that the person logged into the system is actually the person who is authorised to log in.

This is meant to put an end to health workers passing on their login details to outsiders, as two-factor authentication will directly implicate them if fraudulent activity is detected from their accounts.

Thirdly, officials are also conducting ongoing audits to match the details of every person who has received a vaccine to the unique identification number listed on the vaccine bottle from which the vaccine was administered.

“Every vaccine has a unique number or ID,” explains Sikander, “We can now track which person got which vaccine and where, or if they did not actually get a vaccine at all.”

Still, realistically speaking, some kinks remain in the process, Sikander warns.

“There has never been such a major vaccination drive in Pakistan’s history, and that too in such a short time,” he tells Geo.tv.

“It is a big exercise. There are thousands of people with login access; hundreds of vaccination centers all over the country. There is always a chance to game the system.”

Having seen off three major waves, Pakistan has recorded nearly 1.26 million cases of the deadly virus, while over 28,000 people have died as of October 9. As of September 29, Pakistan had fully immunised 12% of its total population.