Experts weigh in on Supreme Court’s interpretation of Article 63(A)

SC had sent back president’s query on imposing lifetime ban on defected MPs, but if lawmaker votes against party lines, then vote will not be counted

May 17, 2022

The Supreme Court has sent back the president’s query on imposing a lifetime ban on defected parliamentarians but added that if a lawmaker voted against party lines, then the vote will not be counted.

On March 21, President Arif Alvi filed a reference in Pakistan’s top court to seek an interpretation of Article 63-A of the Constitution, which deals with the disqualification of lawmakers on grounds of defection.

The reference was submitted after an alliance of opposition political parties sought to remove the then prime minister Imran Khan from office through a vote of no confidence.

The ruling coalition at the time had feared that its own lawmakers would cross the floor, giving the Opposition the required numbers to de-seat Imran Khan. However, on the day, rebel members of the PTI abstained from voting and Khan was instead ousted with the support of the former government's allies.

Although in Punjab, PTI lawmakers did vote in favour of the no-confidence motion to send packing Khan’s hand-picked chief minister.

In the reference, the president had asked the Supreme Court for a “robust, purpose-oriented and meaningful interpretation” of Article 63(A) to “root out the mischief of defection” by disqualifying the dissident parliamentarians for life.

The five-member Supreme Court bench, headed by the chief justice of Pakistan, began hearing the case on March 21 and concluded it on May 17.

'Not to count vote, is against Constitution'

It was a good decision by the Supreme Court to send back the question regarding permanent disqualification, but not to count the lawmaker’s vote, as this is against the Constitution, in my opinion.

I would have to agree here with the two dissenting judges. There is no restriction in the constitution to prevent someone from voting. Instead, the constitution has put in place a punishment for voting against party lines, meaning that the person will lose his/her seat in the assembly.

While the verdict is of advisory nature, it is also binding. Since this is a decision by the Supreme Court it will definitely have to be implemented.

— Ahsan Bhoon, the president of the Supreme Court Bar Association

'It can create a crisis in Punjab'

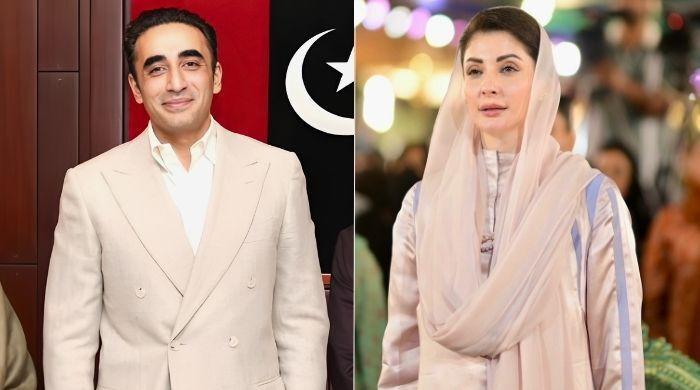

This verdict will have no effect on what happened in the national assembly, but in Punjab, if the vote of rebel lawmakers is disregarded then Chief Minister Hamza Shehbaz loses the majority. In such a case, the election of the chief minister will have to be held again. Although, the detailed verdict of the Court will clarify this.

The Election Commission of Pakistan will have to now decide, in light of this verdict, about the members of the provincial assembly in Punjab who voted against party lines to elect Hamza Shehbaz.

This can create a crisis in Punjab.

— Muneeb Farooq is a lawyer and talk-show host

'Punjab chief minister's election may be held again'

The Constitution states if no candidate for chief minister gets a majority — 50% of the total membership of the house in the first round of election — then a second round will be held. However, in the second round, the candidate will not need 186 votes, instead, he/she can win with the majority of members present in the house that day.

After the verdict, it can be said that the April 16 election of the chief minister in Punjab may be held again between the two candidates, Parvez Elahi and Hamza Shehbaz, or the issue will go to court, which will likely be the case.

The verdict also means that now a lawmaker cannot vote against party lines on the vote of no confidence or money bills, etc.

— Salman Akram Raja, advocate Supreme Court of Pakistan

‘Historic decision'

The Supreme Court’s interpretation of Article 63(A) is historic. The plea to reject dissident lawmakers' vote has been accepted and has eliminated horse-trading permanently. Today’s decision has expanded the parliamentary form of the system.

Under Article 189, the administration, legislature, and judiciary are bound to implement the decision. After the verdict, Hamza Shehbaz is no longer the chief minister of Punjab. There is no other option apart from holding fresh elections.

— Ishtiaq Ahmed Khan, member Pakistan Bar Council (PBC)

'Sound short order'

This is a sound short order which interprets the spirit of Article 63(A) robustly whilst correctly leaving the decision of length of DQ to the Parliament.

The order should logically apply prospectively though; hard to envisage any other interpretation.

— Reza Ali, lawyer

'Practically no value left in defecting'

The opinion purports to ground itself in democratic principles and perhaps it is to a fault. Many wondered whether the court would go to the extent of reading a lifetime disqualification into Article 63(A) to prevent it altogether.

It’s appreciable that the court didn’t, in this case, go so far as to read in a disqualification period as it has done in the context of 62(1)(f); it left this to Parliament. However, it still effectively reaches the same result through an answer to another question instead - whether or not the vote ought to be counted. Here, the court curiously holds that the ‘true measure’ of the law’s ‘effectiveness’ would be if no person can be a defector to begin with. Now, a dissenting vote will not be counted altogether thus incurring disqualification for no gain. So, to that extent, there’s practically no value left in defecting.

But this comes at the cost of other provisions of the constitution which are no less central to a democracy.

For instance, in many cases, a vote of no confidence is now largely redundant. It is also at odds with the line of reasoning taken in relation to the first answer: that Parliament should decide what the law ‘should’ say and that judges decide what the law ‘does’ say.

Parliament has, in the past, included express language to the effect that defecting votes should be disregarded. That provision has now effectively been brought back in not by elected representatives but by un-elected judges.

— Salaar Khan, lawyer

Historic, unconstitutional, legally unsound

— Reema Omer, Legal Advisor (South Asia), International Commission of Jurists