Heatwaves and heavy rains: Why Pakistan’s infrastructure fails every time?

Ever since the 2010 ‘super’ floods struck, more and more Pakistanis are increasingly aware of the fact that their country is in the crosshairs of devastating climate impacts. These impacts have been periodically, or more appropriately, seasonally witnessed.

The natural systems that have been consistent for millennia are suddenly under immense pressure, triggered entirely by human-made global warming.

To put this in the context of history, from the 12,000 years since the last ice-age, the levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere were stable for 98.33% of this time, and the “suddenness” of climate change during the last 70 years is only 0.58% of this period. And it is by sheer misfortune, that developing countries like Pakistan - which have a very small contribution to cumulative global carbon emissions - are among the most vulnerable to impacts.

According to the US think-tank, Berkeley Earth, while the global average temperature today is around 1.2 degrees Celsius, there are regions of Pakistan where it has already exceeded 2 degrees Celsius.

There are corollary variations to all natural systems which come along with these changes, and we can safely assume that increasingly erratic weather patterns in Pakistan, and the larger South Asia region, are being triggered by climate change.

There was another major learning from the 2010 floods. Climate change is also “water change” or more accurately, changes in the water cycle.

The water cycle connects all the various forms in which water exists, from glacial ice to condensed vapours that form clouds. In our region, the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) also impacts this cycle, as the Arabian sea is the westernmost extremity of the ocean. No matter what we do, the proportion of water on the planet remains constant; as some evaporate in one place, it will also rain in another place.

To simplify, changes in the water cycle, and the extent of this change, will always result in an impact at a later period or in another part of the region.

This is also what happened in 2010. At the end of June, a deadly heat wave struck parts of Russia, triggering wildfires and killing an estimated 15,000-55,000 people. By the end of July, the Monsoon was rushing in the direction of Pakistan from the Bay of Bengal. Scientists monitoring the two phenomena saw clear correlations between the two events, with extreme dry heat hitting Russia and Central Asia, followed by extreme rainfall over Pakistan.

A repeat of this appears to be unfolding in Pakistan today. However, the signs of this happening were more clear this time.

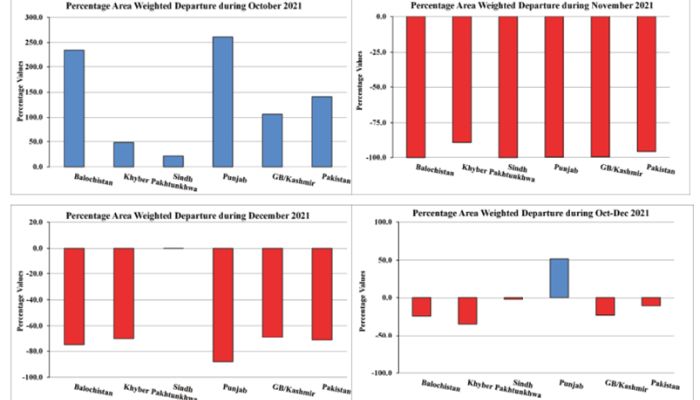

Early 2021 saw the beginning of a prolonged drought over Balochistan and Sindh, and this persisted till the Monsoon. This repeated again, and much less precipitation than normal was received in November and December 2021, and then in February and March 2022.

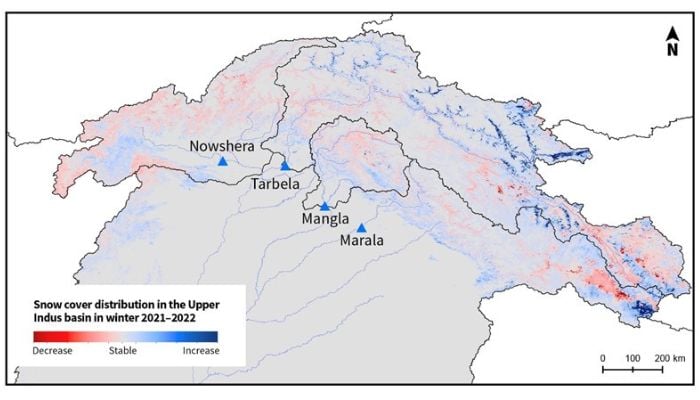

Along with these drastic variations, the mountainous north of the country had been receiving lower snowfall, which translates into much less water in the Indus in Spring. Only as heat picks up in April, does glacial melt provide water. The mighty Indus remained nothing more than streams in parts of Sindh by late May.

Lack of rainfall throughout the first half of 2022 further exacerbated conditions, leading to the longest and hottest heat wave ever recorded in South Asia, over its 122 years of meteorological records. For comparison, the heat wave of 2022 started two weeks earlier than a similar, less intense heat wave in 2010. By the end of March, 13 cities in Pakistan, including the capital, Islamabad, saw the March maximum temperature record being broken.

The difference between 2010 and 2022 is only in the regions being impacted.

The heat wave between March and May, largely, impacted South Asia, rather than a farther region. This changed the resultant impact in two ways. Firstly, the role of the Arabian sea seems to be increasing, as high sea-surface temperatures result in higher convection and stronger coastal weather systems. Secondly, the higher land-surface temperatures in central and southern Pakistan as a result of the dry heat wave, along with other factors described above shifted the impact zone of the severe rainfall largely to the southern parts of Pakistan.

Over the last two weeks, large-scale flooding has occurred in Balochistan, and parts of southern Punjab and upper Sindh.

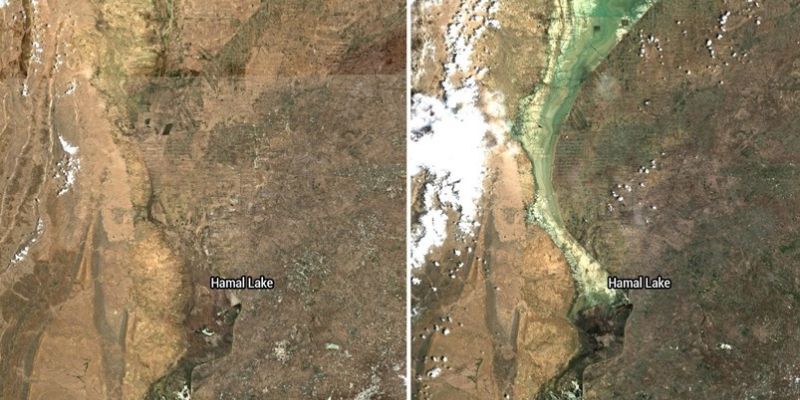

The area between Balochistan’s Dera Murad Jamali and Jhal Magsi has been severely affected, while the dried-up Hamal Lake, to the west of Shahdadkot in Sindh, has not only replenished but also doubled in size to nearly 840 km2, and gradually emptying out as flows pass on to Manchar Lake.

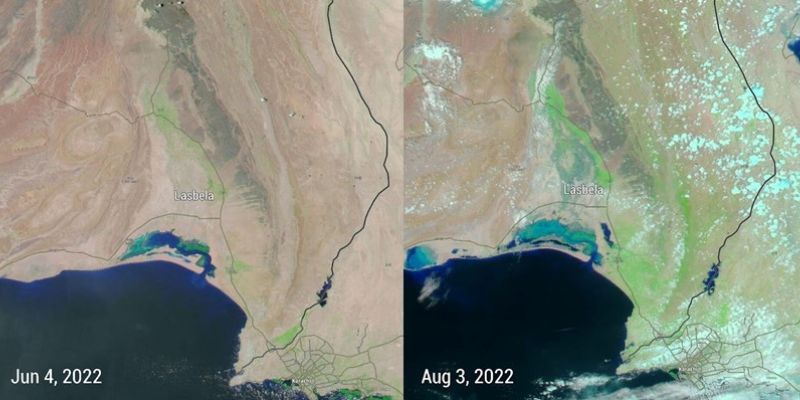

Similarly, Uthal to Lakhra in Lasbela district in Balochistan has been inundated by a week-long rainfall spell and nearby Karachi suffered from urban flooding, as rainfall records broke again; the Masroor air base in the city recorded nearly 24 inches of rain in July.

The worst may be over, however, another rain spell looms over central and southern parts of the country, with some possibility of flooding in Badin, Thatta and adjoining districts.

The Indus, Chenab, Kabul and Ravi rivers are also witnessing medium or low flood levels, which erode flood protections such as dykes, and put nearby villages in harm’s way.

Much of the damages and losses can be prevented by the right disaster preparedness, use of modern data-backed climate and flood forecasting, and timely public communications. Beyond preparedness, it is glaringly clear that our existing infrastructure is ill-designed and under tremendous strain, unable to withstand the expected climate impacts.

The only way forward for Pakistan is to systematically align all policy domains towards resilient, green development, and local-level preparedness that is responsive to information. If policy-makers do not learn from a disaster once, it is likely that a similar disaster will come back to haunt us.

Nauman is a policy analyst and communications consultant. He tweets @thelahorewala.