How General Akhtar revamped the ISI

General Akhtar vastly expanded size and strength of ISI which went from having a staff of 2,000 in 1978 to having 40,000 employees by 1988

August 17, 2022

When the Soviets invaded Afghanistan, Zia asked General Akhtar, his ISI Chief, for an appraisal of the threat posed by the invasion. Akhtar predicted that sooner or later the Russians would invade Baluchistan, seeking a warm-water port on the Arabian Sea. In his assessment, Pakistan was caught between the Russians to the west and India to the east and sooner or later they would join together to destroy Pakistan. To prevent that, he recommended that Pakistan substantially increase its aid to the mujahedin, thereby bogging Moscow down in a quagmire.

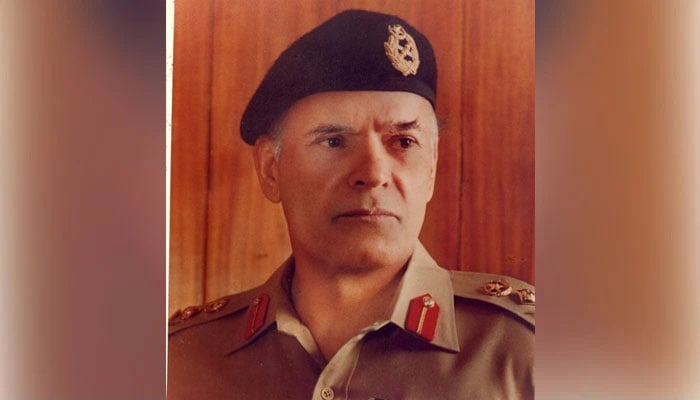

In Zia’s time (1977-1988) the ISI grew under the leadership of General Akhtar Abdul Rahman – better known simply as General Akhtar — a Pashtun who knew the Afghan world well. His own subordinates described him as “a cold, reserved personality, almost inscrutable, always secretive.” Akhtar fought in 1948, 1965, and 1971 wars with India; consequently, he saw India as Pakistan’s “implacable enemy.” He taught for several years at the Kakul Military Academy, and he was posted to England for advanced military training in the late 1960s. Akhtar hated publicity and the press, avoided being photographed, and was “inscrutable” to even his most senior lieutenants, but he was a gifted intelligence officer. He developed close working ties to many of the Afghan mujahedin leaders, especially fellow Pashtuns, and organised them into political parties to give more legitimacy to their struggle.

Akhtar vastly expanded the size and strength of the service. According to one estimate, the ISI went from having a staff of 2,000 in 1978 to having 40,000 employees and a billion-dollar budget by 1988. It came to be seen in Pakistan as omnipotent, allegedly having informants in every village, city block, and public space and tapping every telephone call. Politicians were on its payroll. Much of its growth was intended to keep Zia in power, but much of it was to wage jihad. One of Akhtar’s deputies would later say that “the ISI was and still is probably the most powerful and influential organisation in the country”; he also remarked that Akhtar was “regarded with envy or fear,” even by his fellow officers.

The ISI war in Afghanistan had to be covert. Although Zia and Akhtar wanted to bog Moscow down in a guerrilla war, they did not want to give Russia an excuse to march south to the Arabian Sea or, even worse, to join forces with India in a two-pronged invasion of Pakistan. The pot in Afghanistan had to simmer but not boil, at least at the start; if it did boil, it was Akhtar’s job to make it “boil at the right temperature,” as Zia told him.” The ISI managed the operational aspects of the war. It collected and assessed intelligence from all sources; controlled the supply of arms and equipment arriving in Pakistan for the insurgency; trained the mujahedin; selected the targets for attacks; determined which mujahedin commander got aid and how much; and handled liaison with the CIA, GID, MI6 (the British intelligence service), and the intelligence agencies of other allies.

Since Pakistan was taking all the risks, Zia and Akhtar insisted on full Pakistani control of the war and demanded what would later be called “Reagan rules” for managing the relationship between the ISI and the CIA. The ISI would have sole and complete access to the mujahedin. Aside from photo ops for visiting VIPs such as members of Congress, Vice President Bush, CIA big wigs, and others, the Americans had no sustained contact with the mujahedin fighters. All training of the insurgents was done by Pakistani soldiers.

Managing the mujahedin political parties in Pakistan and the commanders of the fighters was an endless headache for the ISI. They constantly feuded among themselves in Peshawar, where the leadership lived in exile, and occasionally fought against each other inside Afghanistan. The only unity of command came from the ISI.

The Pakistani leadership was not only pivotal for the war in Afghanistan, they were also pivotal in the final stage of the cold war, which had dominated global politics for almost half a century. Zia and Akhtar were strategists and diplomats of considerable skill. They put together the coalition of countries that eventually won the war against Soviet aggression in Afghanistan. The Afghan mujahedin could never have done it alone; they were hopelessly divided and remained so even after their victory over the Soviets. While Washington and Riyadh were critical partners in the war effort, they were not on the front lines, taking the greatest risks. Only Pakistan could play that part, and the Pakistani leadership of that time embraced it with passion and enthusiasm. The decision to fight Moscow was an extraordinarily bold move. The ISI knew, for example, that General Akhtar was at the top of the KGB’s hit list, with a huge bounty on his head.

From the earliest days of the Afghan war, Zia had already begun planning for the next stage in the jihad, turning east toward India and Kashmir. Some of the US assistance that was earmarked for the Afghan jihad was diverted to the Kashmir project and the ISI started helping Kashmiris. A series of clandestine meetings between the ISI and Kashmiri militants from Indian-controlled Kashmir were held, many of them in Saudi Arabia. Zia and General Akhtar were directly involved in the Kashmir project. In 1983 some Kashmiris began training in the ISI’s Afghan camps. Zia, Akhtar, and the ISI also reached out to other groups in Kashmir, including the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF), which had been founded in 1977 in Birmingham, England, by Kashmiris living in the United Kingdom. The JKLF was much more sympathetic to Kashmiri independence than to joining Pakistan. It also was reluctant to take ISI help at first, but Akhtar opened talks with the group in 1984, and by 1987 JKLF militants also were training at the ISI camps.

Meanwhile, in the mid-1980s Sikh nationalists sought to create a Sikh homeland in India, to be called Khalistan. In 1983 the Sikh independence movement took control of the Sikh holy city of Amritsar, and the Indian army responded with a major attack on the Sikhs. It ended in a furious military assault on the Golden Temple in Amritsar and hundreds of deaths on both sides. Indira Gandhi, the iron lady of Indian politics, was assassinated by her own Sikh bodyguards a year later.

The largest supply depot for the ISI’s war in Afghanistan was located just outside Rawalpindi at the Ojhri ammunition storage facility. On April 10, 1988, it was racked by a rippling series of massive explosions as 10,000 tons of arms and ammunition went up in smoke. More than 100 people died in the disaster, including five ISI officers. In 2012 two former Indian intelligence service officers told me that it was their agency that had sabotaged the facility, to punish Pakistan for helping the rebels in the Kashmiri and Sikh revolts.

Zia died before the war ended, on August 17, 1988, when the C-130 transport aircraft carrying him, Akhtar, and the U.S. ambassador to Pakistan crashed into the desert. They had travelled to a remote training facility to observe a demonstration of a new US tank, which had performed poorly. After lunch, Zia and his entourage were to return to Islamabad; instead, everyone on board was killed. Much of the high command of the Pakistani army was dead.

The crash remains a mystery today. An investigation by a joint Pakistani-US air force team concluded that the crash was the work of criminal acts and sabotage, but it did not identify the perpetrator. In fact, there seemed to be no interest among either the Pakistanis or the Americans in identifying the perpetrator of the crash.

It is interesting to speculate on how history might have changed had Zia and Akhtar lived. Some have argued that, unlike Benazir, they would have provided the discipline and cohesion that the mujahedin needed after the Soviet withdrawal to take Kabul in 1989; they would then have ended the war early. Zia and Akhtar certainly would have been determined to fight to victory and not settle for the years of stalemate that in fact followed. Instead, their suspicious death ultimately left Pakistan without the decisive victory that they craved and a very unstable region.

This article is based on excerpts from the book ‘What We Won: America’s Secret War in Afghanistan, 1979–89’ by Bruce Riedel. The excerpts have been compiled/edited for the article by Asghar Khan.

Riedel is a senior fellow and director of the Brookings Institution. He had a thirty-year career at the Central Intelligence Agency and has served as senior adviser on South Asia and the Middle East to four US presidents, working as a senior member of the National Security Council. In 2009, President Obama made him chairman of a strategic review of American policy in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Originally published in The News