Divided by borders, united by aspirations

A young agricultural researcher in Lahore taps into his passion for writing and peacebuilding with a heartwarming multilingual “family” writing workshop

September 11, 2022

“Who and how can anyone say that Southasia is divided?” asked senior journalist Namrata Sharma, editor of Nariswor (Women’s Voice), in Kathmandu. The divisions, she said, come from “different politics”.

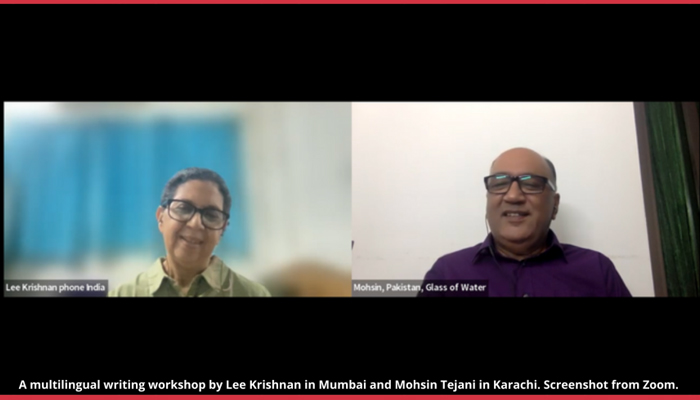

“My heart reaches out to you,” she added, addressing Lee Krishnan in Mumbai and Mohsin Tejani in Karachi, the facilitators of a workshop titled ‘Write for Peace’. “The way, in such a short time, you made us all write, think and connect, was beautiful.” Sharma was delivering the closing remarks at the event on the last Sunday of August, organised by the Southasia Peace Action Network, or Sapan. The interactions she had witnessed and participated in highlighted “the very essence of the existence of Sapan”.

KID AT THE TABLE

I have been part of Sapan since its launch meeting in March last year. Many of us try to take out time from our full-time jobs to help voluntarily organise for this network of intergenerational activists, academics, journalists, researchers, tech people, and more. Sapan activities bring forward issues that concern all of Southasia, creating linkages around shared trials and tribulations.

I try my best to contribute more, but am often unable to make it to the events and meetings. Yes, guilty as charged! But Sapaners treat me like that much-loved kid in the family who is allowed to leave the family dinners without guilt trips. Not very ‘Southasian’ at all!

That’s how we welcome and accept someone. This is the safe space we have created, where people are not judged or put on trial for who they are or what they do or not.

Hearing about this event awakened a spark in me that had lain dormant for years. I RSVPed at once. Writing and literature have always been my passion. I yearned to create experiences, to bring characters and feelings to life. This was that family dinner which I couldn’t miss even as Pakistan and India’s cricket teams battled it out at the Asia Cup.

BREAD LOAF FRIENDS

Lee and Mohsin, friends since meeting at the Andover Bread Loaf writing academy in Massachusetts 25 years ago, designed the workshop keeping in mind Sapan’s ethos and values.

What they put together gave us an opportunity to take a pause, breathe, reconnect, share, and get to know each other better. The online writing workshop brought our community together, to share, celebrate and cherish the bonds of love, friendship, and harmony.

Both are longtime educators. Lee is a teacher, animal rights activist and co-directs Andover Bread Loaf Rising Loaves Summer Programme for middle school students. Mohsin is the founder-director of The School of Writing in Karachi, director of Andover Bread Loaf, and the current president of SPELT, the Society of Pakistan English Language Teachers.

Feminist activist Khushi Kabir in Dhaka hosted the event, terming it “one of the most enlightening, invigorating, energizing” she has attended.

Before the workshop, we had the In Memoriam segment as always, remembering the visionaries and mentors who devoted their lives to the cause of peace in Southasia, as well as those who passed on recently. One of the most prominent names was legendary singer Nayyara Noor, as physician and human rights activist Dr. Fauzia Deeba said, sharing the presentation made by journalist Sushmita Preetha in Dhaka.

Her native Balochistan awash in floods, on behalf of all of us, Dr Deeba also took a moment to talk about the devastation unfolding in Pakistan. Sapan has since issued a statement of solidarity with the flood victims and called upon governments of the region to step up to help Pakistan.

We also had the Sapan Founding Charter, this time read out by educationist and activist Benislos Thushan in Jaffna. “It is truly an inspiring experience to see Sapan, showcasing an action, the common humanity in this region,” he said.

His commitment to the cause of Southasian solidarity also shone through in his joining at short notice, undeterred by a power cut or the overnight bus to Colombo he was about to catch.

RULES TO LIVE BY

Great things are done by a series of small things brought together, to paraphrase a thought from the great artist Vincent Van Gogh. That’s what Krishnan and Tejani did. They divided the workshop into a series of prompts which helped participants reflect, imagine and appreciate.

The six rules preceding the exercise were as simple as our lives are complicated – rules to live by, not limited to a writing workshop. And it is lovely that they were read out in various languages – Urdu, Hindi, English, Bangla, Tamil and Sinhala.

Anyone who follows the first rule “Be kind”, will accept diversity, be empathetic and open their hearts to love.

The rule, “Speak your truth”, reinforces the need for authenticity.

“Write in any language” is a cue to be true to yourself.

“Don’t fear your mistakes” is a reminder that we are human. Don’t be hard on yourself. We learn from our mistakes.

The rule to “Share if you want to” offers participants a choice. If you don’t feel like opening up, THAT’S FINE! Your presence here is enough – thank you for being here.

The last rule “Have fun!” is a particularly essential one,

Lee and Mohsin then walked us through various prompts, gave us time to write, and then opened the floor for participants to share if they wanted.

ENVISAGING PEACE

The prompts invited us to share how we envision ‘peace’ – what does ‘peace’ taste, smell, sound, and feel like? This elicited a wide range of insights – from rosogolla to garlic and butter; from chaat where flavors exist individually together to water on parched lips, giving a sense of hope and a new life.

Some associated the sound of peace with Bach’s symphony. For others, it invoked a coming together of the call to prayer, azaan, and temple bells, or birds singing and joyful laughter.

What does peace feel like? The ‘thumbs of a massage therapist’, or a sofa stuffed with goose feathers.

The variety of reflections gave participants a chance to feel ‘peace’ with all their senses, while at the same time showcasing what peace meant to each one.

The second prompt, “I dream of a world”, was an opportunity to mindfully envision the world we yearn for – for ourselves, for future generations. It was heartwarming to hear the thoughts and ideas that evoked the picture of a world without hostilities, a world that nourishes and gives birth; a world full of love, warmth, and life.

Or as veteran activist Lalita Ramdas put it, “a world that allows you to meet your family in another country, a world without borders, prejudice, and discrimination”. Her Pakistani son-in-law has not been able to visit her and her spouse, retired Navy chief Admiral Laxminarayan Ramdas in India for over five years now.

The flow of energy that this prompt set in motion was palpable. We felt hopeful. We felt connected. We felt alive. We felt human.

The last prompt brought us together at one big table. As Lee said, this prompt was meant to bring out the richness and diversity of the cultures we bring to the table. “What food we share, what conversations we have, in the end, this is what we mean by family. Family doesn’t mean just blood ties, but shared values, and dreams.”

The diverse range of cuisines at ‘our table’ ranged from daal bhaat and roasted turkey, to sattu-filled parathas in green spinach mixed atta and biryani. The conversations we jotted down were no less fascinating, encapsulating fashion, politics, sports, business, literature, art, history, science, and more.

The workshop provided a safe space to open up, share what we felt, and connect with one another. This event made us feel like a FAMILY.

And it got me writing again.

Waqas Nasir is an educationist working as a senior project officer at Science Fuse, a social enterprise in Lahore that works to improve the quality of science education in Pakistan. He hosts an online talk show JALI Talk Show.

This is a Sapan News syndicated feature originally published by Southasia Peace Action Network.

Sapan's note on Southasia as one word: Following the lead of Himal Southasian, we use ‘Southasia’ as one word, “seeking to restore some of the historical unity of our common living space, without wishing any violence on the existing nation states”. Also, writing Sapan like this rather than all caps makes it a word which means ‘dream’.