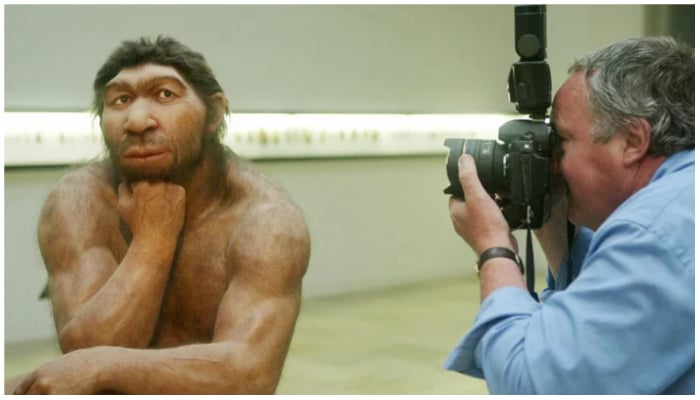

Original Flintstones?: First 'concrete picture' of Neanderthal family revealed by DNA

Study used DNA sequencing to look at social life of Neanderthals, finding women were more likely to stray from cave than men

October 19, 2022

The original Flintstones? The largest genetic study of Neanderthals ever conducted has offered an unprecedented snapshot of a family, including a father and his teenage daughter, who lived in a Siberian cave around 54,000 years ago.

The new research, published in the journal Nature on Wednesday, used DNA sequencing to look at the social life of a Neanderthal community, finding that women were more likely to stray from the cave than men.

Previous archaeological excavations have shown that Neanderthals were more sophisticated than once thought, burying their dead and making elaborate tools and ornaments.

However little is known about their family structure or how their society was organised.

The sequencing of the first Neanderthal genome in 2010, which won Swedish paleogeneticist Svante Paabo the medicine Nobel prize earlier this month, offered a new way to discover more about our long-extinct forerunners.

An international team of researchers focused on multiple Neanderthal remains found in the Chagyrskaya and Okladnikov caves in southern Siberia.

The scattered fragments of bones were mostly in a single layer in the earth, suggesting the Neanderthals lived around the same time.

"First we had to identify how many individuals we had," Stephane Peyregne, an evolutionary geneticist at Germany’s Max Planck Institute and one of the study’s co-authors, told AFP.

‘Seem much more human’

The team used new techniques to extract and isolate the ancient DNA from the remains.

By sequencing the DNA, they established there were 13 Neanderthals, seven males and six females. Five of the group were children or early adolescents.

Eleven were from the Chagyrskaya cave, many of them from the same family including the father and his teenage daughter, as well as a young boy and a woman who were second-degree relatives, such as a cousin, aunt or grandmother.

The researchers also worked out that one man was a maternal relative of the father because he had a genetic phenomenon called heteroplasmy, which only passes down a couple of generations.

"Our study provides a concrete picture of what a Neandertal community may have looked like," Max Planck’s Benjamin Peter, who supervised the research along with Paabo, said in a statement.

"It makes Neandertals seem much more human to me," he added.

Genetic analysis showed that the group did not interbreed with its nearby relatives such as humans and Denisovans, hominins discovered by Paabo in caves just a few hundred kilometres away.

However, we know that Neanderthals did breed with homo sapiens at some point — Paabo’s research also revealed that almost all modern humans have a little Neanderthal DNA.

Rampant inbreeding

The community of around 10 to 20 Neanderthals seems to have instead bred largely among themselves, displaying very little genetic diversity, the study found.

Neanderthals existed between 430,000 to 40,000 years ago, so this group was living in the twilight of its species.

The study compared the community’s level of inbreeding with endangered mountain gorillas. Another explanation for the inbreeding could be that the Neanderthals lived in an isolated region.

"We are probably dealing with a very subdivided population," Peyregne said.

The researchers found that the group’s Y-chromosomes, which are inherited from father to son, were far less diverse than its mitochondrial DNA, which is inherited from mothers.

This suggests that the women travelled more frequently to interact and breed with different groups of Neanderthals, while the men largely stayed home.

Antoine Balzeau, a palaeoanthropologist at France’s National Museum of Natural History, said that fossils found in the Sidron Cave in Spain prompted suggestions of a similar Neanderthal community there, but far less complete genetic material is available.

Balzeau, who was not involved in the latest study, said it was "a very interesting technical feat".

But "it will have to be compared with other groups" of Neanderthals, he added.