The follies of fertility: She doesn’t want more babies…

Thirty-something Safia, the wife of Saleh Mohammad, was five months pregnant when I met her one Friday morning in October at the Basic Health Unit + Khanpur, a 24/7 government primary healthcare facility, where she had come for her first antenatal checkup (ANC).

This is among the 1,2325 of the 2,000 or so health facilities, in all of Sindh’s 29 districts, run by the People’s Primary Healthcare Initiative (PPHI-Sindh), a non-profit under a public-private partnership model started some 16 years ago.

Belonging to the village of Behram Chandio, in Dadu, which had submerged under the flood waters, she, along with her husband and five kids, had taken refuge on the embankment of the Main Nara Valley Drain (MNVD), along with thousands of others. “We were rescued by the Navy and brought to dryland on a boat after our homes were swamped with floodwaters.

“My timing is not good,” said the mother of five, referring to her eleventh pregnancy in a time of crisis and displacement. Floods or no floods, it was an unplanned pregnancy. “We even went to a doctor for termination but were told it was too late to get an abortion,” said her husband Saleh.

“The first two kids are alive, the third died, the fourth survived but the following three died,” Safia paused and started recalling and the counting started again. “The eighth survived, the ninth died and the tenth is alive.”

The couple knew of some modern contraceptive methods but were yet to use them. Safia wanted to space her births but could not. According to the Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey (PDHS) 2017-18, the average birth interval between babies in Pakistan is two-and-a-half years, although 37% of births still occur within 24 months of the last birth.

Safia did not look too well. She said she was running a fever, complained of body aches and said there was too much pressure on her abdomen making it difficult to carry out daily chores or even walk too long.

With delivery time nearing, she was getting anxious. Four of her deliveries had been at a private clinic in the city of Khairpur Nathan Shah, of which two were through Cesarean section. The uncertainty of not knowing when they would go back to their village or whether the clinic was still there was gnawing at her, as was the fact that they had no money to bear the expenses.

For previous deliveries at a health facility, she said, her husband, a farmhand, would sell a goat. “This time we do not even have those assets,” she said, having lost their livestock to the floodwaters.

Saleh's worries were even bigger and too many. “When we return to the village, it will mean rebuilding the house from scratch.” But even more importantly, how will he be able to feed his family? At the embankment they were visible and got something to eat “even if the rations lasted half the month”, he said and feared once back in their village, they would be forgotten altogether.

But if they are sure of one thing, it is to ensure Safia does not get pregnant again. Sterilisation is something Saleh has in mind for her, but he said no to vasectomy (male sterilisation).

The couple is too late in limiting their family size, but Saleh said if he got a second life, he would limit the number of kids he would have. “Only a father knows the agony of putting his child to sleep on an empty stomach, and I have way too many who are not getting enough to eat!” he said and his eyes welled up.

225 million and still going strong!

On November 15, there will be eight billion of us on the planet. Globally, the population is growing at its slowest rate since 1950, having fallen under 1 % in 2020. In Pakistan, on the other hand, with a population of 225 million people, the national growth rate stands at 1.91% and adds at least 5.2 million people every year.

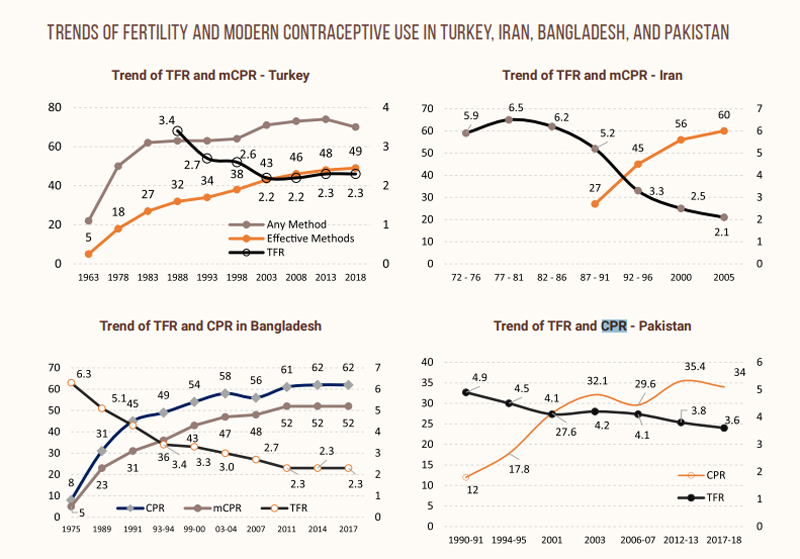

The country's total fertility rate (TFR) — which is the number of babies born to a woman during her reproductive cycle of ages between 15 and 49 — stands at a whopping 3.6 births per woman according to the PDHS 2017-18, a marginal decline from 3.8 in 2012-13. It is also higher than the whole of South Asia (2.4). In Saudi Arabia, it is 2.34. Today it is the fifth largest country after China, India, US and Indonesia.

And if Pakistan does not do anything, its population will reach 350 million by 2050. At the time of independence, it was 36 million! It will mean more malnourished kids who will also remain out of school, longer power outages, and more unemployment.

Four-month-pregnant Anila Abdul Razzak had also come for her ANC at the same health facility as Safia's. She had to wade through knee-deep water from her village of Dur Mohammad Abro to find refuge on the MNVD.

“Two of my kids, aged eight and seven, held on to my hands as we made our way through the water. I kept worrying about what if we slipped and drowned as the current was very strong,” she said, her face tense as she relived the horror. Her husband carried the two younger ones, one on his shoulder and the other in his arms.

This was her fifth pregnancy, but unlike Safia, Anila used contraceptives but still got pregnant.

“I tried to space after my second kid and used pills, but I would forget and I think that could be the reason why I got pregnant; the next time I got a coil (intrauterine contraceptive device — or the IUCD), but it didn’t suit me so got it removed and got pregnant again.”

Begum Deedar, from Ibrahim Chandio goth, is three months pregnant. For over two months, she and her family have been living in a tent on the MNVD, having waded through waist-deep water. She already has five kids aged eight, six, four, three and two. All her kids were born in a health facility, she said.

“This was totally unplanned,” she admitted, adding: “We already have too many kids.”

She was taking birth control injections but missed her three-month dose when the rains began and she was unable to reach the health facility.

What should the state do to help people like Safia, Anila, and Begum not be burdened with unwanted babies over and over again? The Population Council has estimated that over 600,000 women are currently pregnant in the most severely affected rural areas and over 70,000 of them are delivering monthly.

Of the ten million pregnancies in Pakistan, 4.5 million are unintended or mistimed,” said demographer, Dr Zeba Sathar, country director of the Population Council of Pakistan. They want to use family planning but are unable to, she said.

The reasons could be several but according to Dr Sathar, the more prominent ones are “lack of services or choice of contraceptives near or where they live". In addition, the discontinuation rate is high due to many myths around contraceptives which needs to be broken with more information.

But according to Dr Azra Ahsan, president of the Karachi-based non-profit, Association for Mothers & Newborns (AMAN), the biggest barrier has been not communicating directly about the benefits of family planning and the contraceptives methods available to the masses in so many years, by the government. “We talk in an ambiguous, in-between manner, never directly, with the result, no one comprehends the real message,” she said, referring to the public service messaging being given on the electronic media.

Dr Iqbal Shah, a research collaborator at the Department of Global Health and Population, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, proposes the use of technology to reach women like Safia, Anila, and Begum. With over 50% of women in Pakistan now owning a mobile phone, and its coverage, getting closer to being universal (95% in 2019), there was a huge potential to tap into “mHealth options for messaging, reminders, referrals and follow up” as have been done elsewhere.

Pakistan’s contraceptive prevalence rate — CPR (the proportion of women of reproductive age or their partners who are using a contraceptive method at a given point in time) of 34.5pc is dismal compared to Iran’s, which is 77.4pc or Turkey’s which is 73.5pc.

“Pakistan has the lowest CPR compared to other countries in the region, including Bangladesh, India, Nepal, and Sri Lanka, or Muslim majority countries like Iran and Egypt,” said Dr Shah.

Some of the reasons for the low CPR, he said, included: low priority accorded to family planning by successive governments; devolution to provinces slowed the progress as different provinces allocated funding to family planning differently; inadequate information and counselling to women either during home visits by lady health workers or during contacts with health facilities at antenatal care (ANC), postnatal, immunisation or other visits, lack of mass media engagement to disseminate information and generate demand for family planning; low status of women – low education; limited or no decision-making power.

Dr Zafar Mirza, the former special advisor to the prime minister on health, said: “Unless the government makes population and family planning its highest priority,” the nation cannot make much headway in stemming the population. Along with that, he said, the provinces and the central government have to join hands together in this battle.

He recalled that the former chief justice of Pakistan, Justice Saqib Nisar, constituted a task force to resolve the “unbridled population” with the prime minister as its chair. But the prime minister was too busy to chair it even once and the reins were passed on to President Arif Alvi finally.

Without the “executive punch” said Dr Mirza, “with much less than required resources made available,” the task force failed to take off and even when meetings were held, those were “lukewarm” affairs.

“When you’re in the government, you are firefighting on so many more urgent fronts, those that are simmering remain on the back burner without realising that these will have a far deeper impact; this is the same with population,” he said. But Dr Mirza warned: “Population is not just a development issue, it is a security issue and will impact every sphere of life.”

But with a majority of births taking place in a health facility, the answer perhaps lies in strengthening and equipping these brick-and-mortar buildings where health workers can promote birth spacing, counsel couples about modern contraceptive methods, and where family planning commodities are available.

While Anila wanted to space her births and even tried using contraceptives, she got pregnant. Her failure can be attributed to her not receiving proper counselling. Except for Islamabad where the government’s departments of health and population welfare have merged, those in the provinces work in silos.

“Health services work round the clock and deliver babies,” explained Dr Ahsan. But they are bogged down with unprecedented workload at the tertiary care hospitals. Little wonder they have no time to counsel. Furthermore, she said, doctors were generally apathetic and “not clued-up about population issues”. However, the cadre of counsellors that the population welfare department (PWD) has, does not work beyond 2:00pm and are unwilling to work in shifts, although babies are born at their convenience, be it day or night.

“Even if a woman delivers at PWD’s office time, they leave without getting counselling or FP services because the staff is not present at birth to counsel the mother about postpartum FP,” said Dr Ahsan, but even when a woman goes to the private health facility, she was not provided FP service for fear that it might ruin their business!

That was why, Dr Ahsan said, it was imperative the health and PWD integrate. “There are no two ways about it!”

Thumbnail image: Women from the Ibrahim Chandio village, living in tents on the MNVD, talk about their miseries living as displaced persons. — Photo by author

— Zofeen T. Ebrahim is a Karachi-based independent journalist.