Climate extremes in 2022, such as Pakistani floods, call for more action: UN

WMO chief says one-third of Pakistan was flooded, resulting in major economic losses and human casualties

December 24, 2022

- Need to cut greenhouse gases underscored in report.

- WMO chief stresses on need to enhance preparedness.

- Report states Pakistan experienced soaring heat in March and April.

From extreme floods — like those in Pakistan — to heat and drought, weather and climate-related disasters have affected millions and cost billions this year, the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) — a Geneva-based UN agency — said Friday, describing the “tell-tale signs and impacts” of intensified climate change.

The clear need to do much more to cut greenhouse gas emissions was again underscored throughout events in 2022, said the agency, advocating for strengthened climate change adaptation, including universal access to early warnings.

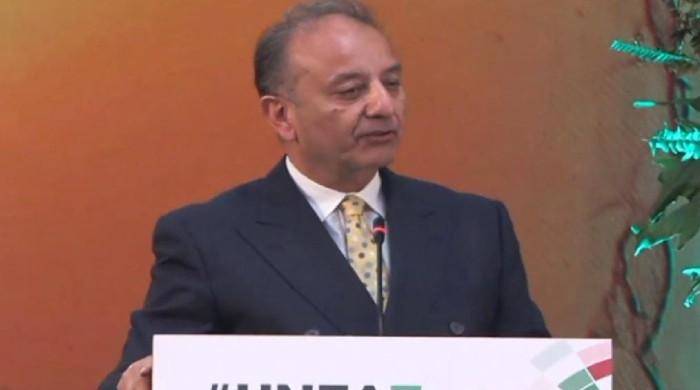

“This year, we have faced several dramatic weather disasters which claimed far too many lives and livelihoods and undermined health, food, energy and water security, and infrastructure”, WMO chief Petteri Taalas said in a statement.

Record-breaking rain in July and August led to extensive flooding in Pakistan, which affected 33 million people claiming 1,700 lives and displacing 7.9 million people.

"One-third of Pakistan was flooded, with major economic losses and human casualties," Taalas said.

According to WMO, global temperature figures for 2022 will be released in mid-January, but the past eight years are on track to be the eight warmest on record.

While the persistence of a cooling La Niña event, now in its third year, means that 2022 will not be the warmest year on record, its cooling impact will be short-lived and not reverse the long-term warming trend caused by record levels of heat-trapping greenhouse gases in our atmosphere.

Moreover, this will be the tenth successive year that temperatures have reached at least 1°C above pre-industrial levels — likely to breach the 1.5°C limits of the Paris Agreement.

Early warnings, increasing investment in the basic global observing system and building resilience to extreme weather and climate will be among WMO priorities in 2023 — the year that the WMO community celebrates its 150th anniversary.

“There is a need to enhance preparedness for such extreme events and to ensure that we meet the UN target of Early Warnings for All in the next five years”, said the top WMO official.

WMO will also promote a new way of monitoring the sinks and sources of carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide by using the ground-based Global Atmosphere Watch, satellite and assimilation modelling, which allows a better understanding of how key greenhouse gases behave in the atmosphere.

Greenhouse gases are just one climate indicator used to observe levels. The sea levels, which have doubled since 1993; ocean heat content; and acidification are also at recorded highs.

The past two-and-a-half years alone account for 10% of overall sea level rise since satellite measurements started nearly 30 years ago, said WMO’s provisional State of the Global Climate in 2022 report.

And 2022 took an exceptionally heavy toll on glaciers in the European Alps, with initial indications of record-shattering melt.

The Greenland ice sheet lost mass for the 26th consecutive year and it rained — rather than snowed — on the summit for the first time in September.

Although 2022 did not break global temperature records, it topped many national heat records throughout the world.

India and Pakistan experienced soaring heat in March and April. China had the most extensive and long-lasting heatwave since national records began and the second-driest summer on record. Parts of the northern hemisphere were exceptionally hot and dry.

A large area centred around the central-northern part of Argentina, as well as in southern Bolivia, central Chile, and most of Paraguay and Uruguay experienced record-breaking temperatures during two consecutive heatwaves in late November and early December 2022.

“Record-breaking heatwaves have been observed in China, Europe, and North and South America”, the WMO chief added. “The long-lasting drought in the Horn of Africa threatens a humanitarian catastrophe.

While large parts of Europe sweltered in repeated episodes of extreme heat, the United Kingdom hit a new national record in July, when the temperature topped more than 40°C for the very first time.

In East Africa, rainfall has been below average throughout four consecutive wet seasons — the longest in 40 years — triggering a major humanitarian crisis affecting millions of people, devastating agriculture, and killing livestock, especially in Ethiopia, Kenya and Somalia.