Mission Majnu: Threadbare thriller about Indian tailor-spy in Pakistan 'needs stitches'

Taking its storytelling structure into account, Mission Majnu did not turn out to be a bad movie; the film is mediocre, at best

In Mission Majnu, a Netflix original production, a strapping young hunk of a tailor falls for a beauty (Rashmika Mandanna) who tends to playfully hold hands and spin in the middle of a bustling bazaar with her friend.

Ah, to be a carefree beauty from Bollywood. So delicate, so innocent, so instantly loveable, so utterly oblivious to the world and it's working.

Pampered by make-up artists to look naturally beautiful, and lit by the lighting director to appropriate the audience’s attention (the few dozen mirrors catching her reflection on a wall at her back do offer a helping hand — this girl is in every corner of the frame, literally!).

Her radiance — and the aftereffects of her mid-bazaar spin that wooshes slow bursts of wind towards the young tailor, scattering the shop receipts behind him — is enough to sell the romantic notions of this typical love story.

Like any love story, there are dilemmas that the romantic song playing in the background glosses over: the girl is blind, and her father, with his dark, fake, black beard and angry eyebrows, is the staunch obstacle in her love life.

Akin to any father with a sensible head on his shoulders, he doesn’t trust the young man’s intentions; after all, the guy, mesmerized by the girl, just accepted a job with a 300-rupee stipend. He must be a true "Majnu" — ergo, the gist of the title.

This majnu’s mission, however, is not to woo the lady. Consider this a happy consequence, or his own side-quest if this were a video game, for he is an Indian spy who has infiltrated Rawalpindi with a cover so deep that even his cohorts have no knowledge of his existence.

The story has a Raazi-like spin, the movie starring Alia Bhatt as an Indian spy in Pakistan — though much more commercial and flippant.

Praying in a masjid that should technically be in Lahore (the tower of the Wazir Khan Mosque stands high above Lahori streets in the first shots of the film), the young hero — Sidharth Malhotra — who goes by the name of Tariq Hussain but is actually Amandeep Singh, is given the mission to find Pakistan’s new-sprung nuclear facility in the wake of India and Pakistan’s nuclear-arms race in the 1970s.

The year specific to the film is 1974, and the narrator, RN Kao — played by Parmeet Singh —, the spymaster of India’s security agency Research and Analysis Wing (RAW), tells the viewers that Pakistan is aggressively setting up a response to India’s nuclear test in Pokhran, historically dubbed as “The Smiling Buddha”.

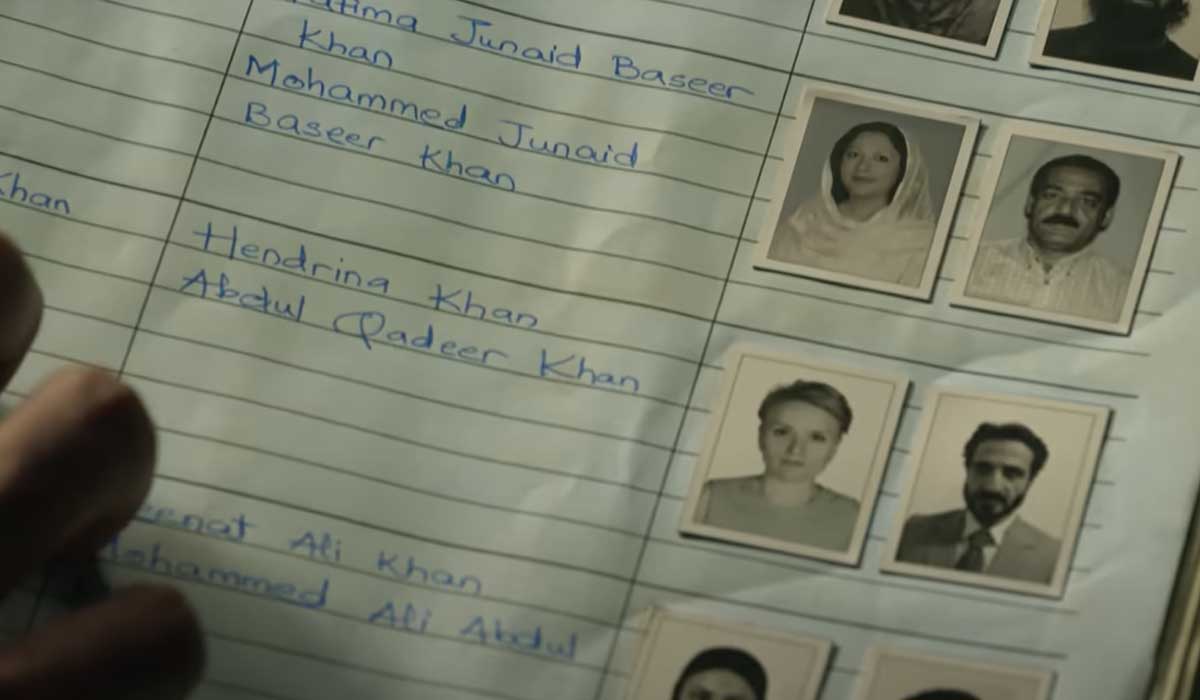

The nuclear test pushed the-then-prime minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto (ZAB), played by Rajit Kapur, who doesn’t really pick up on ZAB’s physicality or mannerisms), to put international pressure on India to stop its nuclear tests, and secretly develop Pakistan’s own programme headed by Abdul Qadeer Khan.

Such devious creatures we Pakistanis are by nature, it seems.

When Indira Gandhi, a staunch supporter of the nuclear programme and RAW’s missions, was superseded by Morarji Desai, a hater of the said agency and the programme, and ZAB was overthrown by General Zia-ul-Haq, Pakistan continued its programme to stalemate India without a hitch, while the latter chose to offer a helping hand.

In a scene, Zia thanks Desai on the phone for the delicious "mithai" the latter sent, and minutes later, happily talks about pushing the nuclear programme onto its next stage with the assembled members of the intelligence.

In a war of covert ops and intelligence-gathering that requires killing, Amardeep has a pacifist inclination, and a semblance of cleverness when one compares him to Bollywood’s usual spy heroes. Rather than smash heads, flung people through windows, or riddle them with bullets (he doesn’t like killing people, be they his enemies), he’d rather do the detective work by sifting through newspapers at the library for leads, and coyly asking gullible old neighbours, school children and store owners to ascertain his findings.

For all the acumen Amardeep exhibits, one wonders why none of it rubbed off on the makers of Mission Majnu.

Produced by RSVP (the makers of Uri: The Surgical Strike), the film stays on-point with the Indian narrative to paint Pakistan as a country of nincompoops, who are also agenda-driven bullies of the subcontinent.

Forget superficial slipups and bloopers, like showing the wrong aircraft in shots (the Boeing C-17 Globemaster III, used to cargo nuclear materials, wasn’t operational until the mid-1990s, and India didn’t get Mirage 2000’s until the 1980s), the screenplay by writers Parveez Shaikh, Aseem Arora, and Sumit Batheja, conveniently twists and turns historical facts and timelines, for dramatic effect.

Case in point: By the climax, (spoiler alert) when the swift retaliation against RAW agents begins in Pakistan, General Zia, unsettled by the possibility of an Indian airstrike that could happen over Pakistan “within fifteen minutes”, orders a stop to the nuclear programme.

As per history, the possibility of this specific airstrike condenses years and skewers timelines. The planned airspace intrusion would have been Israel’s initiative as a follow-up to 1981’s Operation Opera when the Israeli Air Force totalled an unfinished nuclear reactor in Baghdad.

The mission, however, was swiftly scrapped when Munir Ahmed Khan, one of the key scientists of Pakistan’s early nuclear programme, warned Raja Ramana, the chief of India’s Atomic Energy Commission, of a retaliatory strike on India’s Bhabha Atomic Research Center in Trombay, during their meeting in Vienna, Austria.

This diplomatic stalemate took place in 1984 and eventually led to the Non-Nuclear Aggression Agreement between the countries that was drafted in 1988 and came into effect from the year 1991.

That’s, at the very least, nine years after the “fifteen minutes” in the film, where Desai intimidated the government of Pakistan.

Fiddling with facts has been the Bollywood way, since, well, forever. With news anchors, annihilating their windpipes by screaming "bloody murderer" over unsubstantiated statistics and half-facts whenever Pakistan’s name pops up or even when it doesn’t, bamboozling their viewers' senses and scaring the living daylights out of them, one’s logic likely points to the assumption that Indian media has it bad for Pakistan.

In a way, it does. Once upon a time, Bollywood movies used to caricature and lampoon the corrupt fallibility of Indian politics. Giving into the loud obnoxious rush to shock the audience to get ratings, the country’s media has metamorphosed into the very thing it ridiculed: A parody of its former self.

Only now, the two distinctly opposite vocations that should, by nature, be decisively against each other in principle, have seemingly led to the propagation of a warped cultural mindset.

Films, seeing this new normal, followed suit. Their symbiosis is on a molecular level, it seems.

Political differences and issues of state, sovereignty and defence, are always easy fodder for movies — especially when stories about delicate cross-border issues are made. The screaming, and the hype — and the anti-Pakistan propaganda instilled and nurtured during the Modi government’s reign — equal big bucks at the box office as well.

Uri: The Surgical Strike, made in a budget of 25 crores Indian rupees, grossed over 350 crores rupees. Raazi, with its 40-crore rupee budget, made nearly 200 crore rupees.

It took a few decades, but the wild fascination for Pakistan has embedded a gullible premise onto the general public’s waking consciousness. For instance, everyone in Pakistan speaks overly-polished (read: sterilised) Urdu, riddled with "aadaab", "aap", and "janaab", as if they’re from a version of Lucknow one sees in old Bollywood films, or a twisted version of 80s PTV plays, albeit, with bad diction.

When not butchering the delivery with unwarranted niceties, we either stay in desert-like, rundown houses in a landscape mimicking Hollywood’s idea of Iraq or Afghanistan and plot against India; some of us, though, are good people though. Perhaps.

Given the hunky-dory way Amardeep gets his information in Mission Majnu (is it really this easy to find classified stuff out here?!?), one wonders at the great, hypocritical divide in Pakistan’s population. According to the movies, we’re a nation of simpletons and extremists, who speak in the nicest of ways with each other – the soft-spoken, perpetually angry, bad men, plotting against their good neighbour.

Taking its storytelling structure into account, which, from the plot and dramatics' point of view, falls into the stereotypical norms of the medium — and also the nature of the project’s premise — Mission Majnu did not turn out to be a bad movie; the film is mediocre, at best.

The problem it runs into, though, is far bigger than the nukes in the story: it is about being caught in laughable cliches of Bollywood, with no way out. Like the ending of the movie, it is a sad story to see, that’s mostly, an amusing fantasy.

Farheen Jawaid is a long-standing film critic with a career nearing 18 years writing for numerous national publications. When not writing about movies, she consults in the development and production of feature films. Her recent film credit is the supernatural thriller Future Imperfect, which she wrote and helped produce. She prefers not having social media profiles.

Disclaimer: The viewpoints expressed in this piece are the writer's own and don't necessarily reflect Geo.tv editorial policy.