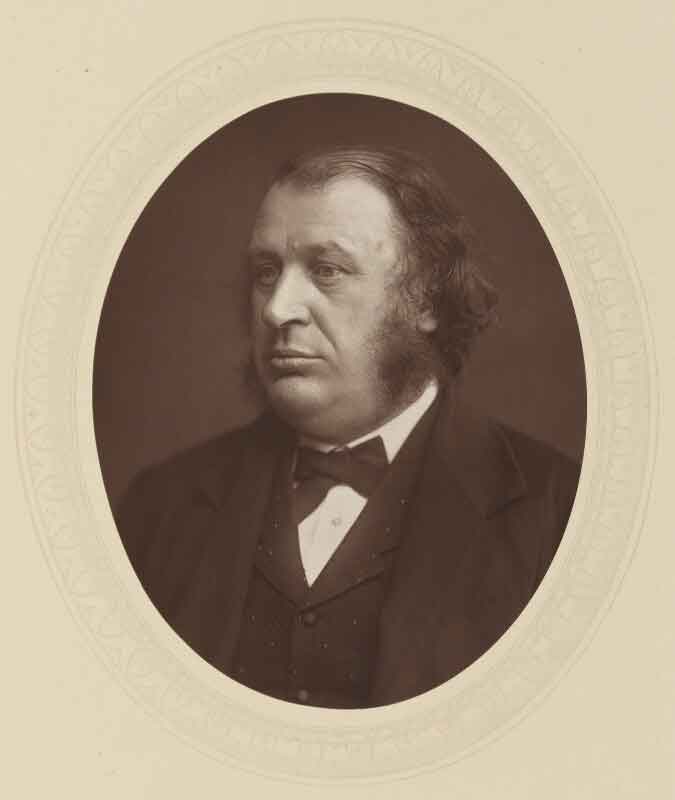

James Fitzjames Stephen: The man behind Pakistan's sedition law

To understand a law's proper historical and political context is to understand its purpose and results it achieved

February 13, 2023

"Power precedes liberty — …liberty, from the very nature of things, is dependent upon power…." Thus wrote the English lawyer, judge, writer and philosopher, James Fitzjames Stephen in his book 'Liberty, Equality, Fraternity' (1873).

Stephen, a defender of old English liberalism, was a proponent of the concept of 'Ordered Liberty'. He was first a friend but later a critic of John Stuart Mill and his treatise 'On Liberty' (1859), a major source today for free speech advocacy. Stephen's own lesser-known book, in which he criticised Mill, was said to be partly inspired by his experiences in India. Between 1869 and 1872 he was a legal member of the Viceroy's Executive Council in India and on the Indian Law Commission. He had a major hand in shaping Pakistani law.

Aside from his grim view of human nature and disdain for Mill's conception of individual liberty, Stephen believed in the inequality of men and women and believed that women, being the weaker sex, would not be able to enjoy the protection of men, if men and women were placed on the same legal and educational footing. His discriminatory views extended to political inequality as he was also perturbed by the expanding democracy in England at the time. In 1867 the English electorate doubled, and all adults had the right to vote. He believed universal suffrage would achieve nothing because political power would not change its nature. The person commanding the greatest number would still rule. Strength in whatever form would still determine ultimate political power.

In 1867, Stephen was given the high-profile task to prosecute the governor of Jamaica, Edward Eyre, for wrongly ordering the court martial and execution of a Jamaican political rival and critic for involvement in the Morant Bay Rebellion of 1865. Oddly during the court hearing, Stephen was observed praising Eyre as a courageous man who had acted honourably in an emergency to suppress a rebellion. This would obviously contribute to the failure of the prosecution and showed his sympathies towards a racist authoritarian.

In 1869, Stephen went to India and drafted the Indian Evidence Act and reworked the draft of the Indian Contract Act, both inherited by Pakistan and effective to this day. His most interesting, but unsurprising, contribution is the amendment of the Indian Penal Code in 1870 which introduced Section 124A, the law of sedition. In short, Section 124A prohibits words or other conduct which causes hatred or contempt, or excites disaffection (disloyalty or feelings of enmity) towards the government.

Pakistan inherited the Indian Penal Code when it gained its independence. It was considered a masterpiece drafted primarily by the notable English jurist Thomas Babington Macaulay. The first draft of the penal code was completed in 1837 but was enacted in 1860 due to delays. The urgency to enact then was largely prompted by the 1857 Indian War of Independence or the Indian Mutiny as the British called it. The Penal Code was designed to make the imperial authority more effective and legitimate, and there was no better time than after the rebellion.

Macaulay had not included the law of sedition at the time of enactment of the Penal Code in 1860 – perhaps due to his libertarian sensibilities regarding oppressive state powers. He had also followed the lead of the US constitution and limited the offence of treason to levying war (against the state) only, as opposed to English criminal law where treason offences were expansive and included planning the sovereign's death and assisting enemies at war.

In 1870, Stephen inserted all of the missing offences regarding treason and sedition by amendment (sections 121A, 124A, and 125 of the Penal Code). He showed surprise regarding the omissions by Macaulay and considered such offences to be "required in the circumstances". According to Stephen, the law of sedition was necessary to protect the British colonial government in India from dissent and rebellion.

In his book 'A History of the Criminal Law of England' (1883), Stephen strongly advocated for laws against sedition. He was clear that freedom of speech should be limited to protect against the spread of dangerous ideas that could incite violence or overthrow the government. Stephen considered sedition to be an offence against internal public tranquillity but not necessarily accompanied by or leading to open violence.

So why is it that the government could not be expected to tolerate words causing mere hatred, contempt, or disaffection short of incitement to violence? The simple reason is that sedition was seen as a preliminary step that could (but not necessarily would) lead to an actual rebellion. Seditious words were sufficient for the government to be offended, even in the absence of a risk of a rebellion, and to punish such speech. The deeper reason perhaps relates to Stephen's understanding of the social construct within which this law must exist.

Stephen distinguished two types of relationships between rulers and their subjects. One where the ruler is the agent and servant of the subjects, accountable to them and capable of being censured and replaced. The law of sedition was not required in such a relationship. The other type he stated was where "the ruler is regarded as the superior of the subject" and in such a relationship "it must necessarily follow that it is wrong to censure him openly, …mistakes should be pointed out with the utmost respect, and…no censure should be cast upon him likely or designed to diminish his authority." It is clear which relationship between ruler and subjects Stephen preferred, and we Pakistanis are not in the least unfamiliar with such a relationship. We have had our share of rulers, civilian and military, which viewed their relationship the way Stephen did during the Victorian era.

The Penal Code and the Criminal Procedure Code were held to be great legislative achievements. Some may argue that it would be reductionism to dismiss such legislation as essentially an exercise in power. In other words, they say, just because it is colonial does not mean it is bad. This argument is not without merit. However, it would be oversimplifying a teleological approach to law reform. To understand a law's proper historical and political context is to understand its purpose and the results it achieved. This in itself is essential to understand whether such law is consistent with our modern democratic values as enshrined in our constitution. While some colonial laws may be benign, others were designed to bring about a particular result which served colonial government interests. The question is whether we are willing to allow our government to preserve those interests.

Stephen admitted the purpose that the Penal Code and Criminal Procedure Code served: "I can only say that it enabled a handful of unsympathetic foreigners…to rule justly and firmly about 200,000,000 persons…The Penal Code, the Code of Criminal Procedure, and the institutions they regulate…are extremely well calculated to protect peaceable men and to beat down wrongdoers, to extort respect, and to enforce obedience." Extorting respect and enforcing obedience is precisely what the law of sedition is used for today.

Sedition, as originally understood, should be distinguished from actual incitement to violence and insurrection. This point was made clear by the Privy Council in the case of Emperor v Sadashiv Narayan Bhalerao, PLD 1947 PC 32, where it approved of the distinction between exciting in others bad feelings (disaffection) towards the government – sedition, and exciting mutiny or rebellion. It held that incitement to violence was not a necessary ingredient of the crime of sedition.

In 1958, the Peshawar High Court ruled in effect that in light of the Constitution of Pakistan (1956) which recognised the right to free speech, it would not be an offence of sedition if there was no encouragement of violence (PLD 1958 (WP) Peshawar 15). This was a well-meaning innovation and departure from the Privy Council decision and the original understanding of sedition by the Peshawar High Court. It is a clear indication that prohibiting speech short of incitement to violence is inconsistent with the right to free speech. Our courts have not considered this point specifically; however, a number of judgements appear to read in the requirement that the offending speech must have a clear tendency towards violence.

All this simply shows that the law of sedition serves no useful purpose today. Rather than interpreting the law to change its meaning, it is best to do away with it. It is not needed to protect public order or national security. Anti-Terrorism laws and other offences against the state in the Penal Code are sufficient and can be improved to cover those aspects, particularly in situations where there is dangerous speech which actually incites people to violence.

Today the law of sedition has been mostly done away with in other jurisdictions. England abolished it in 2010. Australia replaced it with anti-terrorism legislation in 2005/2006. The Indian Supreme Court has effectively suspended the law since early 2022, recognising that the law was being abused and that it was "not in tune with the current social milieu, and was intended for a time when this country was under the colonial regime." Yet in Pakistan, the law continues and is unapologetically used to suppress government criticism, political dissent, and cries of human rights abuses.

There can be no doubt that the law of sedition is a product of a time when colonisers were desperate to cling to power and legitimise authority. Our government cannot be allowed to proceed on the same agenda. The law of sedition must be repealed.

The writer is a barrister. He tweets @miansamiuddin

Originally published in The News