Reproducing society

A very small number of societies seem to think we can eliminate all violence from childhood

February 13, 2023

Some years ago, when a renowned food outlet was still new and exciting in Pakistan, I visited one of these greasy chicken restaurants in Islamabad with some friends. My friends had brought some nieces and nephews on a day out with their Gora Uncle, who they neither knew nor cared about. In the play area of the outlet, a little boy was pushing his fist into the cheek of one of our nephews. Like a proper middle-class Gora, I gently urged the little boy to take it easy and play nicely. Both boys just stared at me like I was some bizarre creature that had appeared out of nowhere.

One of my friends came over and asked me what was wrong. I pointed to the thug that was pushing his fist into our adorable little nephew’s face (the hand was still in the same place and both boys were still gawping at the strange foreigner). My friend laughed and said this was fine. This is how Punjabis play, he said. He pulled me back to the table and left the boys to their "play".

"What if your sister was here?" I asked, "Surely, she wouldn't tolerate her little boy being picked on like that." My friend laughed and said that if his sister was here, she would be yelling at her son to smack the other boy hard. I guess we were lucky she hadn't come with us.

On a separate occasion, I took some friends from a village to a seminar on domestic violence, and specifically child abuse in Pakistan. While one of the speakers was listing the different forms of child abuse, one of my friends leaned over to me and whispered, "But that isn't child abuse. That's just how children are raised."

Not for the first time, I was more than a little unsettled by people I think I know pretty well. I grew up in multiple countries and have seen first-hand how much variation there is in the tolerance and acceptance of violence. In Calgary, Canada, there were few fights, and they were always treated as big news in the lunchroom. In Houston, Texas, I got my head shoved in a toilet on my first day and no one seemed to think that merited much comment at all. By and large, I didn't find Lahore to be as violent as Texas in the school grounds, but there were fights and people didn't seem too disturbed by them.

On a visit to a rural school in Punjab in 2007, I was told the teachers had stopped using beatings to discipline the boys. The government had ordered that corporal punishment should not be used, and they were abiding by the government's guidance. I have been assured, usually with gales of laughter, that this guidance is not so strictly adhered to across the country. Corporal punishment is apparently alive and well in many schools.

Even if we were to stop teachers from using corporal punishment, however, we would still have the problem of children being violent to one another. And of course, children being subjected to violence in their own homes.

Charles and Cherry Lindholm, one the most influential anthropologist couples of Pakistan, argued that the childhood socialisation that they observed in the Swat Valley, was preparation for adulthood in the society. So, the violence, the attitudes about kin, the ideas about the value of the property, and so on, however upsetting they might be for outsiders, were part of a much bigger system of societal and cultural values. To disrupt that socialisation, might render the children unfit for the society they would come to inhabit as adults.

As a cultural anthropologist, I'm fascinated by the observable range of attitudes to physical violence. It seems to me few if any, societies would celebrate violence between children, but a fair number seem to either not see it at all or see it as an inevitable part of growing up. A very small number of societies seem to think we can eliminate all violence from childhood. Scandinavia seems to be intent on ridding its schools of all violence and while I have no idea if they will ultimately succeed, they do seem to have reduced school ground violence.

How far can we go in changing attitudes about violence without triggering damaging unintended consequences in the system? This is rightly a question for the parents who are raising their children in Pakistan to think about and potentially act on. To act, however, requires that people can first imagine a world without violence — and that may be the hardest ask of all.

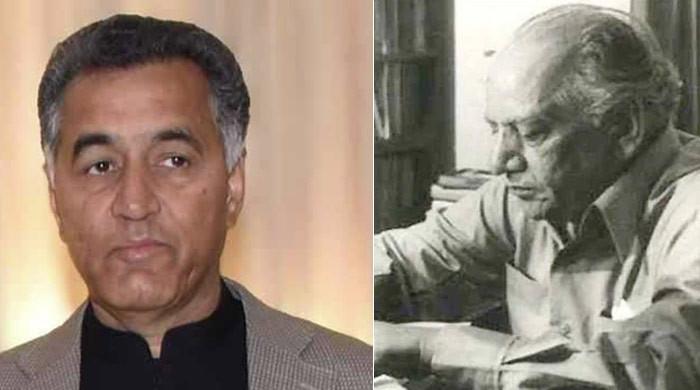

Professor Stephen Lyon is the inaugural dean of Aga Khan University's new Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS). He is a cultural anthropologist with an interest in social organisation, cultural systems, conflict and development in rural and urban Pakistan.