A truth about biodiversity

Supporting biodiversity comes with something of a risk as we must refrain from expanding our human habitation

March 21, 2023

Every morning, I wake up and listen to the incredible orchestra of birds outside my home. There are kites, pigeons, chickens, and other birds whose names I don’t know in any language.

I love listening to these birds arguing and singing and generally being outrageously noisy. From the comfort of my safe home, I don’t worry about a Hitchcock scenario where the birds might decide I am unwelcome.

But the other day, I was standing on a balcony and a kite repeatedly swooped in close to me and squawked. The kite was doing some impressive aerial acrobatics and must have decided that my tea might be only part of what was on offer.

I was reminded that these kites are finely adapted killing machines and I’m only safe because I’m a bit big to look like a meal.

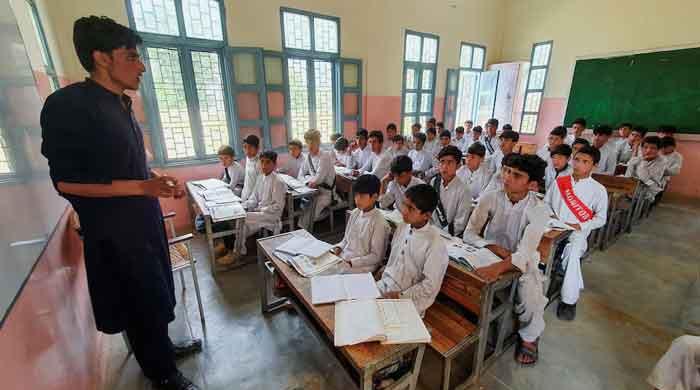

Not for the first time, I reflected on how different my relationship with animals is from that of my friends in rural Punjab.

I was present for the birth of a baby water buffalo, and I was thrilled. I gave the calf a name, Ferdinand, and came by to visit him every day (which wasn’t as dedicated as it sounds, since the buffalo dhera was literally 30 metres from my room).

Local farmers seemed to find it amusing that I would give a buffalo a name. I don’t know what they thought when they watched me chatting away to this calf as if he could understand and was my friend. I developed a lifelong love of water buffalos from that little guy (who soon grew to be a fairly big guy and was then sold on to someone else).

The same pattern repeated itself over and over. I gave names to the farm dogs and talked to them and enjoyed their company. They thought I was mad, or perhaps just eccentric. You put the pattern on repeat with goats, sheep, cows, and cats. I did not befriend the rats, the snakes, the jackals, or the porcupines, but only because we never really seemed to occupy the same spaces at the same time.

Their relationship with the animal world was more pragmatic, but also perhaps more invested. For me, these animals are extensions of cartoon fantasies in which animals can talk and have friendships across species and generally not be threatening.

I learned that even buffalos, the gentlest creatures on the planet, can wreak havoc when they’re upset. Dogs can and do bite. Goats can be a menace to anyone trying to encourage trees. And so on and so on.

And those are the domesticated animals. Wild animals don’t serve human needs in the same direct way as buffalos, cows, goats, and dogs. They have their own agendas and sometimes those pose a threat to people.

I wasn’t seriously threatened by the kite that swooped near me on my balcony, but it reminded me that these birds I so admire, don’t exist for my amusement.

Supporting biodiversity comes with something of a risk. It means sometimes we must refrain from expanding our human habitation. It means we need to rethink our use of quick and dirty chemical pesticides and fertilizers on our crops. It means embracing a little more humility in our relationship with the natural world.

So much of nature does serve humanity very well, so it can be easy to forget that if we want that to be sustained, then we must exercise discipline and not exhaust our planet. When we lose species, it’s forever. If we diminish biodiversity, we ultimately compromise the viability of life as we know it on our precious earth.

I can’t claim to have learned this lesson entirely from a Punjabi village, but what I did learn so viscerally from those farmers was that protecting biodiversity is not a cartoon. It doesn’t mean that other species will be our friends or not see us as prey. The very system that we must protect incurs some potential risk to individuals, even as it improves the chances of survival for humanity.

Professor Stephen Lyon is the inaugural dean of Aga Khan University’s new Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS). He is a cultural anthropologist with an interest in social organisation, cultural systems, conflict and development in rural and urban Pakistan.