Revisiting Bhutto and Pakistan’s 'socialist' experiment

PPP founder's core appeal to people for economic change was in idea of "Islamic socialism", enshrined in PPP's interim Constitution

April 28, 2023

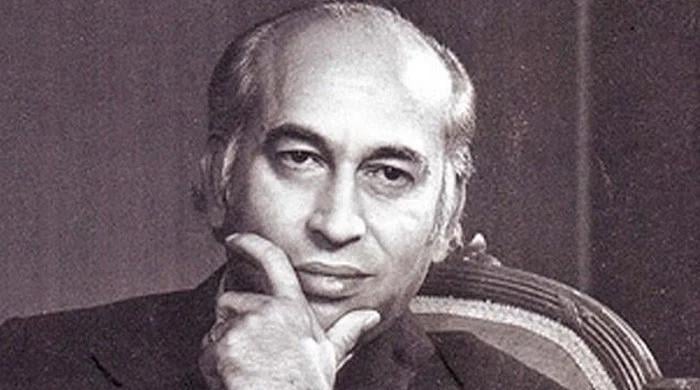

By almost any political, economic or social metric, Pakistan currently endures one of its bleakest chapters, reminiscent of another turbulent period in its history the reign of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, the founder of the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP). Bhutto's political legacy is arguably unmatched, symbolically being a martyr for democracy.

However, this is in stark contrast to his contentious economic legacy. Nonetheless, despite the brevity of his time in power, the repercussions of his policy continue to have a profound impact on Pakistan's economic and social landscape to this very day.

Bhutto's core appeal to the people for economic change was in the idea of "Islamic socialism", which was enshrined in his party's interim Constitution compiled by Jalaludin Abdur Rahim with the words "Islam is our faith; democracy is our polity; socialism is our economy; all power to the people". This Constitution was very effective in gathering a populist support base for Bhutto because it was suited to the social demographics and contemporaneous issues of Pakistan at the time.

Bhutto recognised cries for equality and distributive justice by the lower classes and harnessed their resentment to build political capital. He added Islamist sloganeering for good measure, which meant that a more leftist agenda did not offend the conservative factions and buttressed his support among the masses who were victims of Ayub Khan's unchecked capitalist policies.

Initial challenges

Upon assuming office, Bhutto was immediately confronted with two formidable challenges relating to the dire state of Pakistan's debt-ridden economy: securing funds from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and getting some form of debt relief for loans owed to external lenders. In the wake of the war, severe drought and poor state of the economy, Pakistan's external debt obligations were akin to a ticking time bomb.

A moratorium on external debt repayments was in force since May 1971 which, after multiple extensions, was expiring in May 1972 and, as such, decisive measures were imperative to avert a default. Therefore, to revive the economy, Bhutto began negotiations with the IMF in 1972. Consequently, in response to their advice, Pakistan opted to discontinue the old bonus voucher scheme, which had effectively created multiple exchange rates to reward certain types of exports and imports, and devalue its currency.

The devaluation catalysed the exchange rate undergoing an unprecedented revision with the rupee falling, from a rate of Rs4.76 to the dollar to Rs11 against the US dollar, while retaining its fixed exchange rate regime by remaining pegged to the British pound. In addition to the devaluation, Bhutto also implemented an increase in interest rates from 5% to 6%. As a result of these efforts, Pakistan was able to secure a successful arrangement of $100 million.

The sharp devaluation in the value of the rupee was somewhat reversed in early 1973, when the US Treasury Secretary announced a 10% devaluation of the dollar, which came about due to the fallout from the collapse of the Bretton Woods system. This caused the rupee to appreciate back to Rs9.90 against the US dollar. For Bhutto, this was a good omen and provided welcome relief after getting criticism from certain quarters for the massive devaluation.

For the Bhutto government, the devaluation represented more competitive exports and expensive imports for industrialists, who were the political rivals of PPP. Nevertheless, the slight reversion in the exchange rate after dollar's devaluation managed to lower prices for crucial imports such as wheat and fertilisers, providing much-needed stability.

Alongside the crucial inflows from the IMF, Bhutto also had another challenge to solve: getting relief for Pakistan's past-due debt obligations. He initially had some difficulties domestically, particularly due to disagreements between the PPP, the National Awami Party (NAP) and the Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (JUI), but eventually managed to bring all political forces together. Thus, there was little to no resistance in negotiations with international countries and lenders.

The prevailing debt crisis at that time was very similar to the debt crisis Pakistan confronts today, but domestic unity certainly helped Pakistan while external factors also played a profound role in solving the crisis. While Pakistan was a less developed country, Pakistan's debt obligations still presented a significant concern for major countries, and the health of the global trade and financial system required wealthy countries to prevent smaller countries from collapsing.

Ultimately, the consortium countries agreed to provide a debt relief package of $234 million and a further commodity relief of $280 million. Moreover, reserves of $50 million were made available for the financing of these essential imports. The debt relief plan gave Pakistan until June 30, 1973, to repay its debt to consortium countries. This was followed by another short-term rescheduling of over $107 million provided by both consortium and non-consortium countries between 1973 to 1974.

Although Pakistan had sorted out its near future, a major problem remained with respect to debt and liabilities for projects in former East Pakistan which had now become Bangladesh. Bhutto adamantly refused to pay for these loans and, ultimately, this impasse was broken when consortium countries agreed to Pakistan's demands by not having her pay for the former's debt.

In this respect, the deadlock between Bangladesh and Pakistan was resolved by the consortium countries, who convinced the Bangladeshi government to accept 80% of its total liability. However, on this issue, the role of Bhutto and his government can be lauded by admirers and detractors alike for taking a tough but realistic negotiating stance which allowed Pakistan to successfully sign an agreement of debt relief in June 1974.

Socialist agenda

While some who knew him from his early life doubted Bhutto's personal conviction in socialist principles, he was without question a firm believer in government intervention and the expansion of the public sector as means of garnering populist support. This was apparent in the two main pillars of his economic policy: nationalisation and land reforms, as discussed later.

Bhutto's Manifesto starkly contrasted with Ayub Khan's approach since he was obsessed with transforming and expanding the role of the public sector by increasing its direct involvement in producing capital and essential goods and services while simultaneously incentivising the private sector to establish export-oriented industries.

Nationalisation

In 1972, Bhutto became Pakistan's first civilian chief martial law administrator and undertook a series of socialist economic reforms. Among his key policies was the nationalisation of industries, which he started implementing by the beginning of that same year. Under this policy, Bhutto rounded up 31 industrial units and placed them under the umbrella of the Nationalisation and Economic Reforms Order (NERO). These industrial units included various sectors such as steel, cement, iron, petrochemical, and some public utilities.

The management of these nationalised industries was placed under the Board of Industrial Management (BIM), with the intention of giving the government control of these vital sectors of the economy. The policy, even at first glance, appeared short-sighted as some nationalised units were already in losses and taking them over in the public sector would have meant a further burden to the national exchequer.

The lack of a compensation plan early on in the nationalisation program also caused significant distress among industrialists such as Nasim Saigol, who is reported to have lost 70% of his assets during the process. Widespread reports also emerged of certain industrialist families being harassed, tortured and arrested immediately around the time the policy was announced.

This represented negative optics for Pakistan's business elite which undeniably led private investors' confidence to nosedive. The whole episode created a lasting stigma of Bhutto being "anti-industrialist", a stain which he and his party have had to live with, and struggled to remove, for a very long time, even after his tragic fall at the hands of former military ruler Ziaul Haq.

This was further emphasised when, during the peak of Bhutto's programme in 1974, after a promising recovery following the war, private sector investment started to decline significantly and ended up being reduced to just 15% of its 1970 levels, clearly showing the decline of local and foreign investor confidence during the Bhutto era. Although the nationalisation policy inevitably reduced unemployment levels by almost 58% from 1972 to 1977, production levels did not match this increase.

Bhutto's nationalistic policy was rooted in the growing anger towards the concentration of wealth in the hands of a few, as evidenced by the growing wealth of the top 22 families in Pakistan who owned 65% of all large-scale manufacturing.

The idea to nationalise these industries led by the wealthy captivated and fascinated the middle and lower classes who had bought into Bhutto's "roti, kapra, makaan" rhetoric at the time. However, the sad irony was that they celebrated their own suffering, as the nationalisation programme reversed all the progress Pakistan had made towards industrialisation and extinguished any possibility of sustainable economic growth for decades to come.

Land reforms

Apart from the nationalisation program, Bhutto also introduced another series of radical reforms on March 3, 1972, aimed at redistributing land from landowners to peasants, especially tenant farmers and landless individuals, with the goal of improving agricultural productivity and reducing overall inequality. Bhutto introduced these reforms in response to the growing monopolisation of land and the deeply polarised social landscape that had developed in Pakistan under previous regimes.

This can be seen in data from the Pakistan Census of Agriculture 1972, which showed that only 16 private farms (0.425% of total private farms) comprised over 9% of the total farm area and over 5% of the total cultivated area in the country. This unequal distribution of land ownership created a system of privilege for the wealthy few, while the majority of the rural population struggled with poverty and lack of access to resources.

In response to this, Bhutto's land reform programme tightened the maximum land ceilings, reducing them so that no individual could own more than 150 acres of irrigated land or 300 acres of unirrigated land. This was a change from Ayub Khan's 1959 law, which allowed individuals to own up to 500 acres of irrigated land and 1,000 acres of unirrigated land. Ostensibly, this was aimed at breaking up the large landholdings of the wealthy few and redistributing the land to landless peasants.

Bhutto also introduced land tribunals to settle disputes related to land ownership and transfer, and increased the role of the state in providing credit and other inputs to small landholders. However, these land reforms failed to achieve their goal of reducing the concentration of land in a few hands, as data from the Pakistan Census of Agriculture 1980 showed that only 14 private farms (0.344% of total private farms) comprised over 9% of the total farm area and over 6% of the total cultivated area in the country.

If we compare farmed area, production, agricultural production index, and yields, it can be seen that the immediate years after Bhutto were more productive than his own years. Although major flood and drought events plagued his tenure, the lack of significant rebound after the war can be considered disappointing.

Admittedly, Pakistan was never food secure and relied on food imports throughout Bhutto's tenure. Nevertheless, the land reforms empowered small landowners, tenant farmers, and landless individuals, who received land (and a new lease of life) and were now able to freely invest and reap the rewards by improving their output. This also reduced poverty among its beneficiaries by over half.

In terms of long-term implications, however, the fear of having their lands taken away led to a significant decrease in private investment in agriculture (as a percentage of total investment), falling from 16.8% in 1970 to 11.9% in 1977. Additionally, the lands redistributed to smaller landowners, tenant farmers, and landless individuals led to greater inefficiency and stagnant productivity since these people lacked the capital, capacity, and knowledge to increase crop yields. It is clear that Bhutto's socialist experiment did not achieve the desired results.

Macroeconomic performance and impact of exogenous events

Bhutto's supporters may argue that exogenous factors hindered the success of Bhutto's policies. When Bhutto took over in 1971, he was faced with drought across much of the country, followed by floods in 1973, 1975, 1976, and 1977. The 1973 floods were particularly devastating, although they were partially alleviated through large multilateral and bilateral foreign aid, loans, and grants.

There is no doubt that exogenous factors, such as the 1973 global oil crisis caused by the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) oil embargo and the aftermath of the Arab-Israeli war, greatly impacted the Pakistani economy, just as the Ukraine war, global supply chain crisis, and commodity supercycle have recently hurt Pakistan's economy.

At the heart of this issue is the recurring challenge for Pakistan that major surges in oil prices inevitably lead to a significant increase in import costs, ultimately resulting in a balance of payment crisis. As a result, the prevailing international oil crisis during Bhutto's period led some to argue that Pakistan's economic problems at that time were mainly due to exogenous forces, rather than any endogenous weaknesses in Bhutto's policies and governance. In fact, virtually all non-oil producing nations experienced a significant increase in their current account deficit between the fiscal years of 1973 and 1975.

Before the global oil crisis, Bhutto's economic policies showed promise, as evidenced by Pakistan's impressive GDP growth rate of 7.06% in 1973. However, even this initial growth may have been due to the rebound effect and recovery from the economic losses of the war. This scenario is common after periods of turmoil, and many nations have enjoyed sharp recoveries after wars in the past, such as Britain, which experienced a brief economic boom after the First World War.

But 1973 proved to be an exception as Bhutto failed to replicate this initial success and was unable to deliver consistent growth in later years, where GDP growth remained low at an average of 4.2% in the period of 1974 to 1977. This was a slightly lower growth rate than most South Asian countries at the time, who grew comparatively quicker at an average of 4.6% during the same period of 1974-1977.

From this analysis, it can be concluded that reconstruction from the war was driving most of the growth, along with a significant portion of public spending, whereas growth in agriculture and manufacturing was lagging significantly behind regional peers in the same period and Pakistan's own growth in these sectors in the pre-war period.

Contrarily, Pakistan's relatively modest growth during Bhutto's reign coincided with high inflation. This inflation was before the emergence of the global recession and oil crisis, which hit in early 1974 and caused inflation to spiral further out of control. Despite this, Pakistan's CPI was still far higher than regional peers from South Asia, with an average inflation of 17.6% in the period of 1974 to 1977 compared to other South Asian nations, whose average CPI stood at 10.54% in the same period. This striking divergence in inflation rates suggests that Bhutto's economic policies may have been partly responsible for this high inflation and not just global events.

The devaluation of the rupee certainly was a major factor for the inflationary spiral but another policy under the former premier's era, which may have also contributed significantly, was import substitution through the imposition of increased import tariffs. Conversely, the nationalisation of domestic industries also led to the flight of capital and reduced investments and, ultimately, less competition. The businesses which remained demanded a risk premium for their products and services through high prices, triggering further inflation.

A final note

In view of this discussion, it is not an exaggeration to say that Bhutto's economic policies have etched an indelible mark on Pakistan's economic and social fabric, with the profound impact of his radical economic drive still reverberating to this day and manifesting through ongoing crises and troubling predicaments such as the burgeoning debt of Pakistan Steel Mills.

While his policies may have been well-intentioned, excessive government intervention and desire for a greater role of the state in the markets, reflected in the form of policies such as nationalisation and land reforms, severely disrupted industrial and agricultural productivity and hampered growth. Higher import duties also played a role in lowering production in several industries by increasing the costs of raw material, machinery and spare part imports. Moreover, the lack of foreign competition made many local industries less competitive, further lowering their incentive of being efficient.

Looking at the longer-term horizon, Bhutto's policy of nationalisation led to a severe decline in investor confidence and made it challenging for Pakistan to attract foreign investment in the subsequent decades. In addition, the Bhutto government's dependence on price controls in markets created distortions which created myriad, varied and complex challenges both in that era and in the following periods.

Moreover, the 'stickiness' of his socialist policies has remained a major challenge for Pakistan. For example, many of Bhutto's nationalised industrial and commercial units not only became significant liabilities on the national budget, as they continued to operate due to political pressure due to concerns about potential unemployment if they were to shut down.

Similarly, in order to meet the expectations created by the Bhutto regime, it became politically imperative for future governments to not just carry on various socialist policies he initiated, but to further increase the size of the government in the name of giving 'relief' to the populace, lest they lose face and their vote banks. Admittedly, the negative consequences of these policies were compounded by external factors such as the global oil crisis of 1973, adverse weather events and aftershocks from the loss of East Pakistan in 1971.

Ultimately, the long-term impact of his policies was particularly damaging and may be considered the root cause of the many debilitating challenges plaguing our economy today. In conclusion, it can be said that while Bhutto's political acumen was evident in his ability to unite the country and allowed him to achieve extraordinary feats like the 1973 Constitution and the inception of Pakistan's nuclear programme, his economic legacy will always remain debatable.

The writer is a student of A Levels at a private school in Dorset, UK