What did James Webb Telescope spot this time in deep space?

Observation of 3 rings around Fomalhaut star offers full insight to date about such structures outside our solar system

May 09, 2023

As scientists discover planets orbiting around different stars, it causes excitement but these planets do not offer complete information about the surroundings of the stars without taking into account the debris of rocks and ice orbiting around our sun, reported Reuters.

In a study published in the journal Nature Astronomy, scientists have revealed through their observations carried out by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) providing new details about similar features around the Fomalhaut star — a luminous object in our space neighbourhood of the Milky Way galaxy.

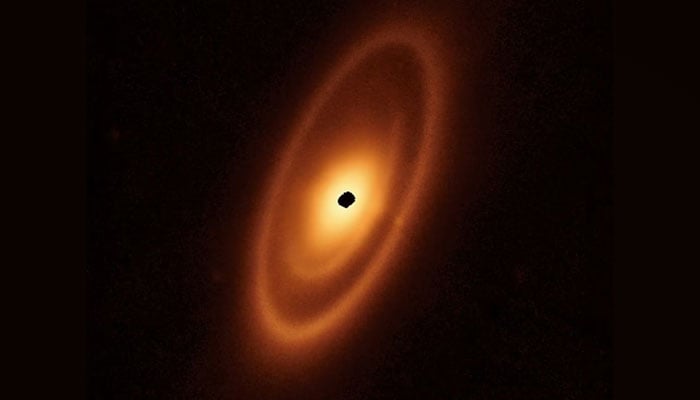

The observation of the three dusty rings around the Fomalhaut star offers full insight to date about such structures outside our solar system.

Fomalhaut is located 25 light years away and is one of the brightest stars in our night sky. It is the brightest in the southern constellation Piscis Austrinus. It is 16 times more bright than or sun and is 440 million years old.

The single belt of debris was first discovered by astronomers back in 1983 however, James Webb Space Telescope revealed two additional rings near the star — one is the brightest in the centre and the two others.

Astronomers from the University of Arizona and the lead author of the study Andras Gaspar said: "Much like our solar system, other planetary systems harbour disks of asteroids and comets — leftover planetesimals from the epoch of planet formation - that continuously grind themselves down to micron-sized particles via collisional interactions."

The revealed belts extend out to 14 billion miles from Fomalhaut, about 150 times the distance of Earth to the sun.

There is no planet discovered around Fomalhaut but the researchers suspect the belts were carved out by gravitational forces exerted by unseen planets.

Our solar system has two such belts — the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, and the Kuiper belt beyond the ice giant Neptune.

The gravitational influence of Jupiter, our solar system's largest planet, corrals the main asteroid belt. The inner edge of the Kuiper belt, which is home to dwarf planets Pluto and Eris as well as other icy bodies of varying sizes, is shaped by the outermost planet Neptune.

Gaspar noted: "The secondary gap we see in the system is a strong indication for the presence of an ice giant in the system."

Astronomer and study co-author Schuyler Wolff of the University of Arizona's Steward Observatory noted: "Nearly all of the resolved images of debris disks thus far had been for the cold, outer regions analogous to the solar system's Kuiper belt, like Fomalhaut's outer belt."

Wolff further stated that "MIRI now can resolve the relatively warmer belts of material analogous to our main asteroid belt."

"Planets form within the primordial disks surrounding young stars. Understanding this formation process requires a complete understanding of how these disks form and evolve," Wolff said.

"There are many open questions about how the dust in these disks coalesces to form planetary embryos, how the planetary atmospheres form, et cetera. Debris disks are remnants of this planet formation process and their structure can provide valuable clues to the underlying planet population and the dynamical histories," Wolff added.