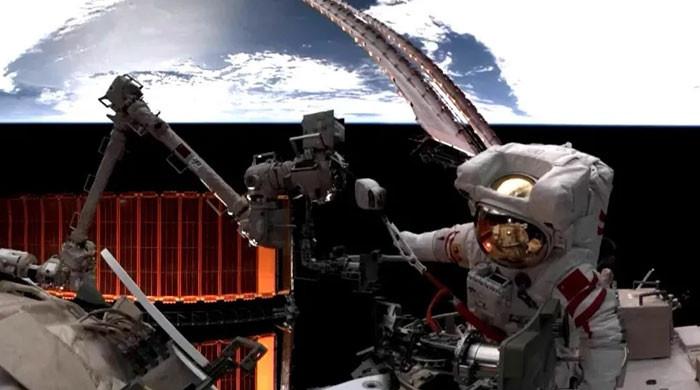

Long spaceflights impact astronauts' brains, research shows

Research shows that astronauts' ventricles expand during spaceflights, necessitating a recovery period of at least three years

June 09, 2023

New research suggests that the brains of astronauts are significantly affected during spaceflights lasting six months or longer, and crew members may require a minimum of three years before embarking on another space mission.

Scientists conducted a study comparing brain scans of 30 astronauts taken before and after spaceflights, ranging from two weeks to a year in duration. The results revealed a notable expansion in the ventricles, the cavities within the brain filled with cerebrospinal fluid, among astronauts who spent at least six months on missions to the International Space Station (ISS).

These findings have crucial implications for future long-duration missions as space agencies like NASA and its international partners aim to establish a continuous human presence on the moon through the Artemis program, with the ultimate goal of sending humans to destinations as distant as Mars. The study detailing these findings was published in the journal Scientific Reports on Thursday.

Cerebrospinal fluid plays a vital role in protecting and nourishing the brain while eliminating waste. However, when astronauts venture into space, fluids within the body redistribute towards the head, exerting pressure on the brain and leading to the expansion of the ventricles.

Lead study author Rachael Seidler, a professor of applied physiology and kinesiology at the University of Florida, explained, "We found that the more time people spent in space, the larger their ventricles became. Many astronauts travel to space more than once, and our study shows it takes about three years between flights for the ventricles to fully recover."

Among the participants, eight astronauts went on two-week missions, while 18 embarked on six-month missions. Four astronauts had missions lasting approximately a year. The researchers observed that the degree of ventricle enlargement varied based on the duration of astronauts' time in space, with the most significant expansion occurring when transitioning from two weeks to six months.

Surprisingly, there was no further increase in ventricular size between six months and one year, indicating that ventricular enlargement stabilises after six months. This finding is positive news for future Mars travellers who may spend approximately two years in microgravity.

Notably, astronauts on two-week spaceflights experienced minimal changes in ventricular structures, which is promising for the burgeoning field of short-duration space tourism.

For astronauts who had more than three years of recovery time between missions, the researchers observed an increase in ventricular volume after each subsequent mission. However, those with shorter recovery periods displayed minimal ventricular enlargement following their most recent flight. This suggests that experienced astronauts may have persistently enlarged ventricles, limiting room for further expansion during spaceflight.

To ensure a full recovery, the research team concluded that astronauts require a minimum of three years between missions. However, further research is necessary to fully understand the long-term consequences of these brain changes on the health and well-being of space travellers. Rachael Seidler is initiating a new project to investigate the long-term recovery and health of astronauts up to five years after six-month spaceflights.

Given the specialised skill sets and training of astronauts, there may be justifications for including them on additional missions before the recommended three-year recovery period. Nonetheless, allowing sufficient time for the brain to recover appears to be a prudent approach to safeguarding the health and behavioural well-being of space travellers.