Kudos to govt on IMF deal. But why the delay?

Pakistan, IMF finally strike staff-level agreement on $3 billion stand-by arrangement, bringing country's economy back on track

July 01, 2023

The latest deal between the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and Pakistan shows that bravado and bold statements on a nation's economy get you nowhere if sustainable policies cannot back them.

Islamabad and the Washington-based lender on Friday finally struck a staff-level agreement (SLA) on a $3 billion stand-by arrangement, which would allow the cash-strapped country to get its economy back on track.

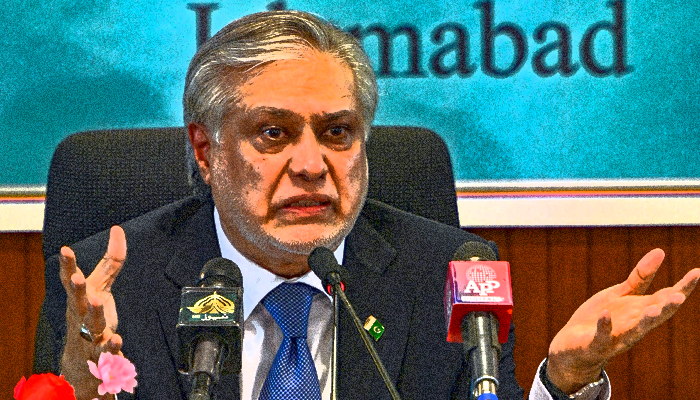

Finance Minister Ishaq Dar, who took charge in September last year, made big claims about how he would stabilise the rupee and achieve economic growth but fell short of his promises.

While he criticised his predecessor, Miftah Ismail, for hiking petrol and power prices in line with IMF's demands, he also had to concede and accept the fiscal policies laid down by the global lender.

His insistence on not accepting the IMF's demands dealt a massive blow to the economy. Without the multilateral fund, Pakistan's financing avenues shrank.

The large-scale manufacturing (LSM) sector shrank by 21.07% in April, the tenth consecutive contraction; inflation surged to historic highs; the rupee fell to new lows; and the stock market suffered losses.

Through this all, the financial czar's mantra that the house was in order continued. However, the crises in the background were of the government's own making.

Left with no option, the government — with mixed signals — claimed that if the IMF refused to release the stalled loan, it would move towards 'Plan B'.

Maybe it was the 'Special Investment Facilitation Council (SIFC)' but on that, too, there was little clarity.

But since there aren't any quick fixes when it comes to Pakistan's economy, the government understood there was no option except the IMF for the time being, despite Dar vehemently declaring he won't take dictation from the Fund.

The government finally made some belt-tightening measures — reducing the expenditure and raising taxes through the budget, lifting a ban on imports, raising interest rates, and allowing the rupee to trade at a market-based exchange rate.

All of this could have been done nine months earlier, according to economic experts, had the finance minister and his government not been insistent on not making tough decisions.

The IMF funding will be available to Pakistan soon, and the executive board will likely give the nod for fund disbursement, but what of the people?

Will the government explain why it failed to implement the IMF's demands earlier? Will Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif — who played a significant role in securing the IMF deal — hold the finance minister accountable? Who will ensure that such politics don't happen again?

India's ex-prime minister Manmohan Singh, according to former SBP deputy governor Murtaza Syed, did not blame others and made corrective decisions for the economy when faced with a similar crisis.

Will we ever learn from our mistakes and steer the economy towards development?