Internationalising a university

Internationalisation offers universities range of benefits that contribute to institutions' overall growth and success

July 24, 2023

I recently had the opportunity to visit Incheon in South Korea’s greater Seoul area.

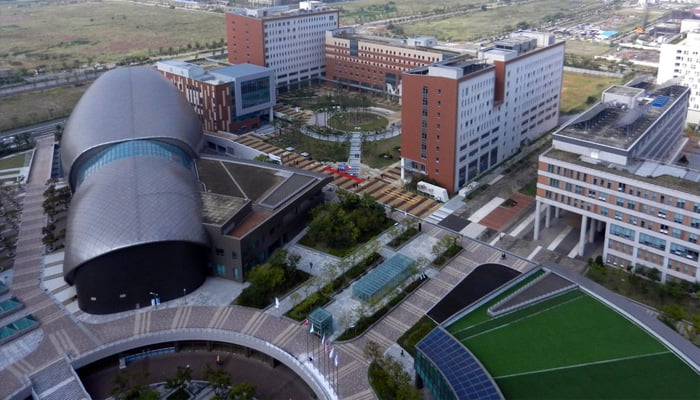

I spent time at the Incheon Global Campus, a global education hub hosting overseas campuses of some of the world’s most prestigious universities, meeting with presidents of four international universities: three American and one Belgian (Ghent University), soon to be joined by another five to six universities that will take it to full capacity.

I also had the opportunity to visit universities in the Dubai International Academic City and Dubai Knowledge Park free trade zones.

These experiences, together with the desire expressed by leaders of some Pakistani universities to establish campuses overseas in their quest to internationalise their programmes and campus culture, piqued my interest on this issue.

The Ghent University (South Korea campus) president considers his campus a bridge between Belgium and South Korea and, in the longer term, the two regions.

Internationalisation offers universities a range of benefits that enrich the educational experience and contribute to institutions' overall growth and success. Internationalisation brings together students and faculty from different countries and backgrounds, creating a diverse learning environment.

This exposure to various cultures, languages, and perspectives fosters global awareness, cross-cultural understanding, and tolerance, preparing students to thrive in an interconnected world.

It offers enhanced learning opportunities, language skills and communication, greater employability and career opportunities, exchange and mobility programmes, a global alumni network, research collaboration, innovation, and improved positioning to tackle global challenges.

There are two approaches to internationalisation: The first is to bring students from across the world to campus.

This entails adapting the admissions process, mechanisms for determining equivalences of educational qualifications of applicants, providing support for finding student accommodations, revamping onboarding processes, supporting student visa applications, and tracking the visa status of arrivals.

It amounts to changes in every office and department of the university but is achievable at a relatively low cost.

The other approach, one employed less frequently, turns that upside down and takes the university to the world by establishing a branch campus overseas, in another part of the world.

Obviously, this approach requires a sizable investment and often an invitation, incentivisation and good relationships with regulatory government departments of the host country.

Data from the Cross-Border Education Research Team (C-BERT) currently puts the worldwide number of overseas branch campuses at 333, spread across 83 host countries.

The top-five countries hosting the most overseas branch campuses are China (47 campuses), the United Arab Emirates (30), Singapore (16), Malaysia (15), and Qatar (11).

The largest ‘exporters’ of overseas branch campuses are the United States (84 campuses), United Kingdom (46), Russia (39), France (38), and Australia (20).

The government of Dubai’s Knowledge and Human Development Authority (KHDA) puts the number of international universities in Dubai alone at 40 (which suggests that C-BERT’s data may be incomplete).

The UAE’s welcoming policy to university branch campuses is rooted in the country’s future strategy which, among other things, seeks to establish it as a regional and global hub for education.

Anecdotal evidence from my own social and professional circles suggest that its approach is bearing fruit; at only a two hours flight-time from Karachi, three hours from Islamabad, and with attractive scholarships available at branch campuses, the UAE is quickly becoming a sought-after study destination for many in Pakistan who can afford to pay more than universities in Pakistan demand, yet cannot shoulder the full cost of tuition and living expenses of North American or European universities.

Over the last decade, a number of first-rate universities have successfully established branch campuses in the UAE.

From the US they include New York University (NYU) Abu Dhabi, the Rochester Institute of Technology Dubai, and the Hult International Business School Dubai.

From the UK, the University of Birmingham Dubai, the University of Manchester Worldwide, City University London, the London Business School, the Strathclyde Business School UAE, Middlesex University Dubai, the University of Bradford, Heriot-Watt University, and De Montfort University. From Australia, the University of Wollongong in Dubai, Murdoch University Dubai and Curtin University.

Even our neighbour, India, has contributed the S P Jain School of Global Management, the Birla Institute of Technology and Science Pilani Dubai, Manipal Academy of Higher Ed, and Amity University, all of which are highly rated by the local regulators.

According to data from C-BERT, the Shaheed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto Institute of Science and Technology (SZABIST) in Dubai is at present the only overseas branch campus of any Pakistani university.

Although it maintains one of the lowest ratings by the KHDA, it seems to be getting by financially.

Interestingly, there are now rumors of more Pakistani universities waking up to this possibility and making their way to the Middle East. Word has it that LUMS is taking its MBA programme to Dubai next year.

NUST, at the insistence of a sizable Pakistani expat community, has also been seen exploring the feasibility of establishing a campus in Saudi Arabia.

At most universities in Pakistan, their understanding of ‘internationalisation’ only extends to admitting children of Pakistani expats and emigrants.

Accepting these students on international student seats allows them to charge higher tuition fees (often in dollars) and raise much-needed funds.

A few universities in Pakistan that have competitive programmes have begun to take steps towards internationalising their campuses by adding support for international students and short-term exchange students, mostly from Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Indonesia, and a number of other countries.

Establishing a branch campus entails the parent institution taking on a significant financial risk. Setting up and maintaining a branch campus in another country requires substantial initial investment and ongoing operational costs.

Some prominent instances of branch campuses that failed to take root in their host countries and closed operations in recent years include the Yale-National University of Singapore liberal arts college, Michigan State University Dubai, University College London Qatar, Reading University Malaysia, and Aberdeen University South Korea.

C-BERT’s count of failed branch campuses currently stands at 58, which underscores the high risk associated with the launch of overseas campuses.

The reasons for failures can be many, such as the challenges of maintaining consistent academic quality across multiple campuses in different countries. The parent institution must ensure that the curriculum, teaching standards, and academic rigor are on par with the main campus.

Any decline in academic quality at the overseas branch campus could jeopardise the entire university's reputation, eventually leading to a complete decoupling between the home and branch campuses.

Overseas campuses must walk a fine line between adapting branch campus operations to the local context, needs, and culture while maintaining the positive elements of the academic culture of their home campuses that make them desirable destinations for study in the first place.

Operating in a foreign country requires navigating different cultural norms, educational systems, and legal and regulatory frameworks.

In doing so, universities may face language barriers, local customs, and administrative complexities that can hinder effective management.

Compliance with local laws and regulations, including those related to visas, academic accreditation, and labour, is essential but can be challenging and time-consuming. Adapting to the local environment while maintaining the parent institution's identity requires careful planning and cultural sensitivity.

In the present environment, where most public universities are struggling to meet their expenses, opening branch campuses may seem like a distant dream.

However, the time may have come for private and some public universities that enjoy strong (regional) reputations and have the ability to raise funds to start thinking in this direction.

As institutions explore these possibilities, it is vital to learn from both successful and failed examples, ensuring that each step taken toward internationalisation is well-informed, sustainable, and aligned with the mission of advancing education and research.

By embracing internationalisation, universities can make meaningful contributions to global knowledge exchange, cross-border collaboration, cultural diplomacy, and the development of future leaders equipped to thrive in an interconnected world.

The writer has a PhD in Education.

Disclaimer: The viewpoints expressed in this piece are the writer's own and don't necessarily reflect Geo.tv's editorial policy.

Originally published in The News