Unpacking implications of Pemra act amendments

One significant amendment to Section 5 involves guaranteeing timely salary payments to employees in the electronic media sector

In the heart of Islamabad, the National Assembly's Standing Committee on Information and Broadcasting convened in the Radio Pakistan office, where the Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority (PEMRA) (Amendment) Bill, 2023 was put forth.

The Minister for Information, Marriyum Aurangzeb, clarified the necessity for this amendment, remarking that the media landscape had experienced a drastic change since the original Pemra Ordinance was introduced in 2002.

This amendment is historic, not only because it is the first time the Ordinance has been modified in this context, but it brings significant reforms intended to protect journalists and hold media organisations accountable. The nine clauses of the Ordinance are amended, five new clauses are added, and journalists are given the right to file complaints in the Council of Complaints for the first time.

The modifications reflect a shift in power dynamics. Previously, the authority to close down a channel lay solely with the Pemra Chairman. The amended law has delegated this authority to a three-member committee. According to Marriyum, the incumbent government engaged in extensive consultations with various stakeholders, including media workers' organisations and media house owners, to reach this revised bill over a span of 13 months.

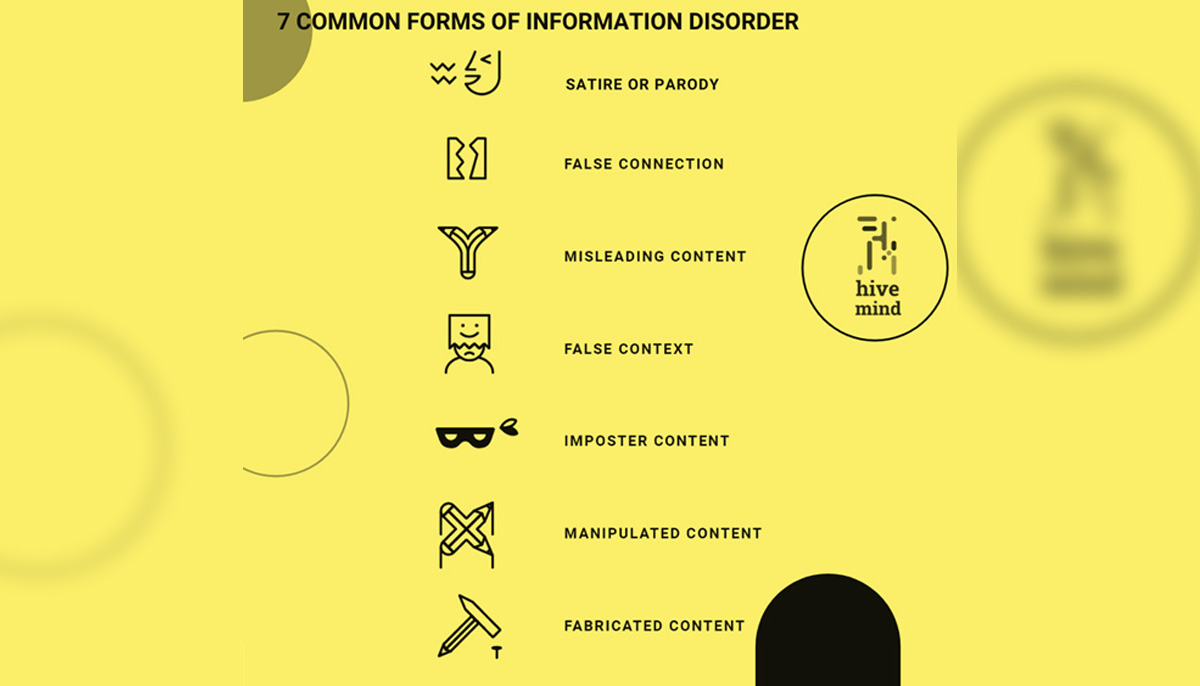

A salient feature of the new bill is to address information disorder, putting more responsibility on content creation and ownership, by inclusion of definitions for fake news, disinformation, and misinformation. Notably, the penalty for deliberately spreading false news or creating information disorder has increased from Rs1 million to Rs10 million. This steep hike is an attempt to ensure that media houses share in the accountability for the news they disseminate. However, the proposed law is still silenced on the definitions, types, and categories of information disorders, leaving loopholes to be exploited later (See table).

| Type of Disorder | Nature of Information Disorder | Societal Impact | Regulator's Role | Responsibility of Content Creator and Media Organisation |

| Satire or Parody | Despite being forms of art, these can be used to intentionally spread rumors and conspiracies. Even when not intended to cause harm, their humorous nature can sometimes fool people, leading to the spread of misleading information | Miscommunication, Misinterpretation, Propagation of rumors. | Monitoring and providing clear labeling for satirical content. | Clearly labeling content as satire or parody, ensuring it cannot be easily misconstrued. |

| False Connection | This occurs when headlines, visuals, or captions don't support the content. While seemingly harmless, false connections can undermine trust in media and promote polarisation. | Distrust in media, Increase in polarisation. | Monitoring and correcting misleading headlines or visuals. | Providing accurate, representative headlines and visuals that align with the content. |

| Misleading Content | This involves the selective use of information to frame an issue or individual. Spotting this form of information disorder requires specific knowledge, research, and source checking. | Manipulation of public perception, Promoting false narratives. | Fact-checking, Identifying and correcting misleading content. | Ensuring fairness and accuracy in presentation, conducting rigorous fact-checking. Establishing fact labs to assist the viewer in confirming the content sanctity. |

| False Context | This involves sharing genuine content with misleading context. A genuine picture, for instance, may be reshared to support a different narrative. | Misrepresentation of facts, Manipulation of public sentiment. | Identifying and correcting contextually false information. | Providing accurate context to all information, fact-checking before re-sharing. |

| Imposter Content | This type of disinformation involves impersonation of genuine sources. It exploits the trust in certain organisations or individuals, often leading to phishing and smishing attempts. | Erosion of trust in genuine sources, Potential for phishing or other scams. | Monitoring for impersonation, Protecting identities of real sources. | Ensuring that all claimed identities are legitimate, reporting potential impersonation. |

| Imposter Content | This occurs when genuine information or imagery is manipulated to deceive. Examples include photos and videos that are altered to convey a different meaning from the original content. | Spreading of false narratives, Manipulation of public perception. | Identifying and correcting manipulated content. | Verifying the integrity of all published media, avoiding distribution of manipulated content. |

| Fabricated Content | This is completely false content designed to deceive and cause harm. Distinguishing between real and fabricated content is often extremely difficult. | Erosion of public trust in media, Spreading of harmful falsehoods. | Identifying and taking action against creators of false content. | Adhering to strict fact-checking processes, reporting and correcting false content |

Source: Hive Mind

The amendments in the Pemra law have sparked intense debates across the country's media and political landscape. The amendments, presented by Ms Aurangzeb, were devised after extensive consultations over a year and aim to ensure journalist welfare, fostering a free and accountable media environment in the country.

Key modifications involve changes in Sections 2, 6, 8, 11, 13, 24, 26, 27 and 29 of the Pemra law. In addition, five new sections, including Sections 20, 20-A, 29-A, 30-B, and 39-A, have been incorporated. These changes intend to widen the news coverage scope, allowing the inclusion of verified news, tolerance, economic progress, and child-related content in electronic media publications.

One significant amendment to Section 5 involves guaranteeing timely salary payments to employees in the electronic media sector, which mandates electronic media employers to make required payments within two months. This change under Section 20-A and 20-B aims to protect employees from non-payment by any broadcast media outlet. As a result, electronic media employees can now legally challenge the non-payment of their dues or salaries.

Despite the intended benefits, these amendments have faced staunch criticism from the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), who reject the bill, citing concerns over curtailed freedom of expression and media freedom. PTI spokesperson criticised the government's attempt to control media and free speech as unacceptable, arguing it to be the worst exploitative and anti-constitutional government in the country's history.

Yet, the National Assembly's Standing Committee on Information and Broadcasting unanimously approved the Pemra (Amendment) Bill, 2023, considering it an extraordinary initiative for journalist welfare.

While certain aspects of the revised Pemra law have been lauded, the amendments have also been slammed for their potential to restrict broadcast media or distribution service operations. Advocates for media freedom argue that while Pemra should ensure channels adhere to the law and refrain from hate speech, it should not act as a censor enforcing an official line for all programming. The ultimate goal should be to establish an independent body like a thinking and research-based regulator, which, despite state approval, can operate independently.

Changes in the amended law focus on the well-being of media workers. The bill states, "Timely payment refers to payments made to electronic media employees within two months." Should media houses fail to comply, they would not receive government advertisements at both federal and provincial levels.

Supporters of the bill emphasise that it brings much-needed reform to the industry. By defining between disinformation and misinformation, the new law aims to reduce the spread of fake news. Additionally, it seeks to ensure fair remuneration for media professionals, even though there are debates about the specified two-month payment window.

Furthermore, the bill introduces a sense of democratisation to the Pemra board by giving representation to the Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists (PFUJ) and Pakistan Broadcasters Association (PBA). However, as these positions are 'honorary' and non-voting, their influence on decision-making remains to be seen.

The bill reflects an attempt to balance media freedom with increased responsibility and accountability in the evolving landscape of Pakistan's media industry. However, the full impact of these changes will only become apparent once the bill is implemented and tested in real-world scenarios.

Countries that media freedom challenges on both sides of the fence, as the regulator and the media entities both play in a gray world of rules and legal stays, it is important that an independent neutral body make decisions regarding the impact of news or programming has had on society, this could be a hybrid of members from academia, professionals, and/or legal fraternity.

This is why the independence of the electronic media regulator is so important. Institutions like the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in the United States of America or the News Broadcasting Standards Authority in India are both state-approved regulators but completely independent. These would be good examples to follow.

The information minister has said that the Media Joint Action Committee was consulted regarding these amendments, which took 11 months to be finalised. The Pakistan Broadcasters Association (PBA) on its part has endorsed the bill. But it may be best to also try and reach out to those media professionals that have reservations regarding these amendments before the bill is passed by parliament.

There is a thinking that Pemra should not be regulating the media entities, however, self-regulation is not an answer for the industry, as regulation gives protection to the licensee in addition to safeguarding the general public’s right to truth and entertainment. That said, there is a need for responsible action by regulators. That means taking to task those who do not follow the basic tenets of journalism without punishing journalism that lives up to its mission of speaking truth to power.

The new amendments introduced measures to protect the rights of media workers. For instance, the new bill gives media workers the right to file complaints in the Council of Complaints and requires media organisations to pay their employees’ salaries, no later than two months, or else face a ban on government advertisements. The journalists could go to CoC earlier, too, but were barred from lodging complaints against their own organisation which this bill has now allowed.

However, this raises concerns about the amendments. While acknowledging the good intentions behind the bill — such as the attempt to tackle disinformation and fake news, and ensure timely payment of salaries to media workers — we should also consider the ambiguities and potential risks. The media controlling mindset of the regulator and the government, their desire to determine the sanctity of the content, in terms of what can and cannot be shown on TV.

It is suggested that an independent body, equipped with the knowledge of “media effect” can be gauged. The science of sociology and psychology are to be included in such a sensitive decision-making process. This is important to ensure the freedom and independence of the media and its positive impact on society.

The provisions aimed at guaranteeing timely salary payments to media workers could significantly affect the media sector's overall structure. Such regulations may prompt industry players to prioritise the commercial viability of their content, potentially resulting in increased commercialism and a dilution of content integrity, specifically in news and current affairs discourse. This could be a very important and effective tool in the coming days of the General and Provincial Elections in the country.

The shift could inadvertently favor businesses that have established media outlets primarily as a form of influential leverage to bolster their commercial interests, coming from non-journalistic backgrounds, they also bring their parent industries’ set of rules and approaches.

Over time, this trend could potentially erode the core journalistic spirit of the media industry. It's crucial to carefully balance economic considerations with maintaining the integrity and independence of journalistic content, in order to prevent a total eclipse of journalistic values by commercial interests and non-professionalism.

As the debate around the amendments to the Pemra Ordinance continues, it remains to be seen how these changes will ultimately impact media freedom in Pakistan. Both the government and media outlets will need to strike a balance between regulating content to prevent disinformation and maintaining the independence and freedom of the press — a task that will undoubtedly prove to be challenging.

The perceived state of governance within the Pemra is a matter of concern and seeks serious attention, with the Pemra website exposing a potentially alarming situation. The regulatory body, overseen by Chairman Saleem Baig, a seasoned bureaucrat with an impeccable reputation, seems to exhibit signs of lax governance and borderline disregard for various governance commitments. However, the primary responsibility lies with the board members of the authority to ensure compliance by the management. The secretary to the board should also be questioned for his negligence in compliance.

Historical policy decisions have also played a significant role in the current state of affairs. During former prime minister Yousaf Raza Gillani's tenure, two actions notably compromised the independence of the regulatory bodies: placing the National Accountability Bureau (NAB) under the law ministry and moving Pemra under the information and broadcasting ministry. These moves allowed the government to use the regulators to its own advantage, often targeting opposition parties and dissenting voices.

The Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) government, in a highly controversial move, had conceived the Pakistan Media Development Authority (PDMA) under the guise of controlling and developing the nation's media industry. Despite its purported innovative approach, the PDMA had been a glaring testament to failure and mismanagement. The authority was rudderless, bereft of clear direction, devoid of a meaningful mandate, and structurally disorganised. There had been a conspicuous lack of institutional trust, with its credibility constantly under fire from media professionals, civil society, and the public at large.

In what appeared to be a blatant disregard for transparency and democratic governance, the PDMA had instead morphed into a disappointing piped dream. The plight of the PDMA underscored the PTI government's inability to effectively administer such critical institutions, reminding us of the indispensable need for comprehensive planning, stakeholder engagement, and an unwavering commitment to the principles of free speech and transparency.

Regrettably, these measures were largely unchallenged, reflecting both a deficiency in civil society's awareness and empowerment and a silence from industry dissenters. With the rise of the PTI government under PM Imran Khan, intense discussions emerged around advertisement revenues and their public sector allocation for media entities. However, the crucial role of the Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan (SECP), the primary regulator, to determine the health and governance of the business entity was largely ignored during these conversations.

The SECP steadfastly stands as the premier supervisory authority for corporate governance, spanning all sectors and industries, including media. Let us imagine a parallel scenario wherein gross mismanagement within corporations arises, compelling corresponding regulators from various sectors — energy, oil and gas, telecom, banking, and so forth — to step in. Legal consequences would naturally ensue unless these issues were swiftly and effectively resolved.

Therefore, we must underscore the pivotal role of regulatory bodies such as the SECP and Pemra in safeguarding the integrity of industries. Their tasks aren't merely administrative; they are the bastions ensuring ethical business conduct, fair practices, and the enforcement of statutory regulations. Their presence underscores the need for constant vigilance in the corporate world and is a reminder of the importance of good governance to the economic health of the nation.

A key area of contention is the functionality of the Council of Complaints (CoC), a crucial mechanism for managing grievances and ensuring transparency and accountability. The new amendments put a lot of responsibilities and influence on the Council of Complaints and its members.

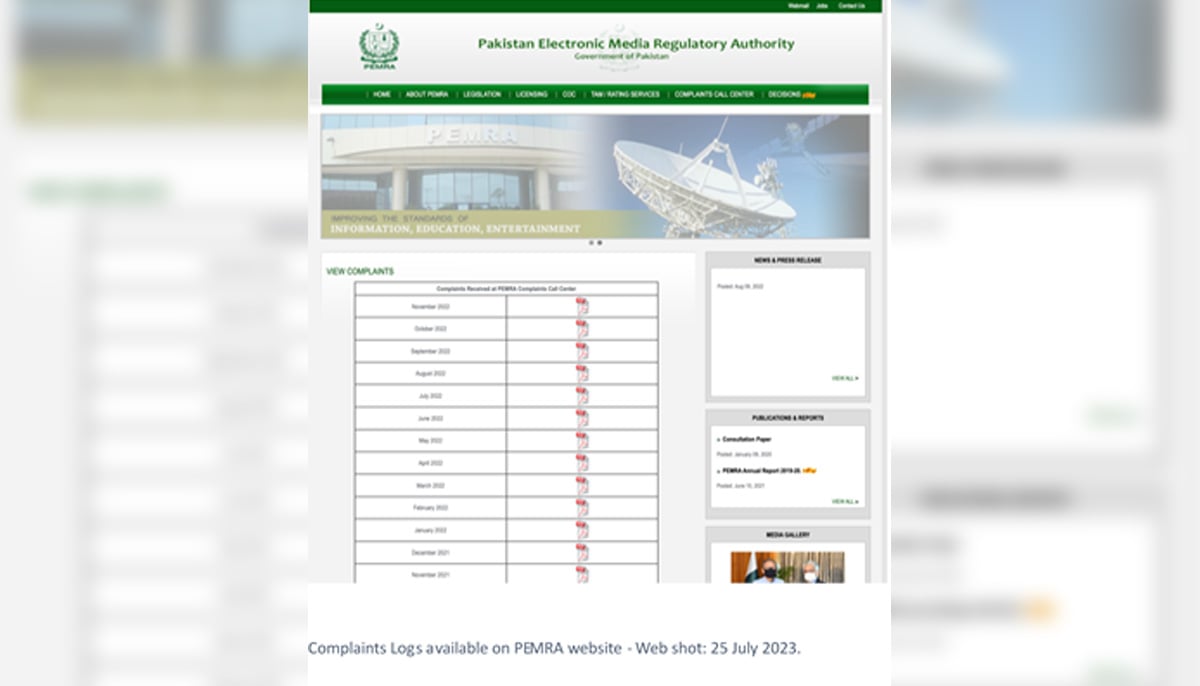

The complaints received by Pemra’s state-of-the-art, call center are compiled and displayed on the official website for public information at the end of each month. In theory, these complaints are presented in the CoC meetings and actions are determined accordingly.

However, the most recent complaint log available on the Pemra website dates back to November 2022, raising questions about the effectiveness and transparency of this system. Furthermore, an in-depth look into the CoC's composition reveals that only the Balochistan Council is currently functional, while the remaining provinces and the federal are redundant or non-functional. This lack of information about the Council's members and their functionality on the website exposes a notable gap in the governance delivery.

Adding to the concerns, the annual report, a statutory requirement for all regulatory bodies, is also not a regular publication. The latest annual report published by Pemra is the one for the year 2019-2020. The report is typically utilised as a reference for industry stakeholders and potential investors, providing vital insights into the media sector's dynamics. Information such as the number of investors, user habits, new technologies or opportunities to be explored, and other crucial research findings are typically included, aiding those interested in exploring media space for possible investment opportunities and job creation.

The conspicuous absence of updated reports from Pemra is troubling, given that clause 17 of the Pemra Ordinance 2002 (amended 2007) mandates annual reporting of its operations and accounts, along with making it public knowledge through reports available to all.

The Board of Pemra appears negligent in ensuring compliance and sharing its operations and financial activities with the public. If left unchecked, such oversight constitutes a breach of trust and should be handled firmly. It is the Board's responsibility to maintain compliance and oversee regulatory obligations, and failure to do so is a matter of public concern and should be subject to parliamentary scrutiny.

Moreover, the website discloses that the last board meeting was held on 17th February 2022, and the subsequent silence and lack of published decisions stand as a stark testament to Pakistan's deteriorating state of media and governance.

Pemra's state of governance appears to be in need of serious reconsideration, with the transparency, accountability, and regulatory compliance of this important regulatory body coming into question. Pemra as a media regulator has the role and responsibility of being the “Custodian of Public Trust” in society.

The lack of thinking and absence of governance is not only eroding the citizen’s trust in public institutions but also damaging the sentiments of the younger generation towards the significance of the country's identity and social values.

Compliance and public disclosure are two crucial elements in the management and regulation of any industry. In essence, they create an environment of accountability, fostering trust and confidence among stakeholders and the general public.

Compliance refers to the adherence to rules, regulations, laws, and standards that govern an industry. For media regulators, this means ensuring the industry follows the laws and regulations on content creation, publication, dissemination, and the ethical guidelines set out by the license agreement between the regulator and the licensee. Compliance in the media industry can also relate to the observance of laws relating to copyright, defamation, and privacy, among others.

Public disclosure, on the other hand, relates to the openness and transparency of an organisation’s operations, including the regulator. For media entities, this could involve disclosing information on ownership, funding sources, and editorial policies. This openness helps in creating a more transparent media environment where audiences can understand who is behind the content they consume, which in turn aids in fostering trust and credibility.

In the context of Pakistan's media industry, the importance of these elements is magnified due to several challenges that have stunted the industry's growth and cognitive abilities. These challenges range from political pressure and censorship to financial instability and lack of professional training. The limited vision of stakeholders and the pursuit of short-term business interests by key industry players have often overshadowed the broader societal role of the media.

The new amendments to the media regulations offer an opportunity to address these challenges. They can help to create a more robust and transparent media industry, provided that the amendments are designed and implemented in a thoughtful and balanced manner.

However, as these amendments are being compiled and reviewed, it's important to note that they shouldn't be evaluated solely by technocrats and sector specialists. While these individuals bring a wealth of knowledge on the technical and industry-specific aspects, social scientists bring a unique perspective that should also be considered.

Social scientists can provide insights into the societal impact of these amendments. They understand societal trends, behaviors, and the interplay between different societal factors. As such, they can forecast how these amendments might affect the society, culture, and political landscape of Pakistan, ensuring that the resulting regulations are not only technically sound but also socially beneficial.

The primary objective of the amendments should be geared toward enhancing the operational effectiveness and efficiency of Pemra as a regulatory body. The overall functioning of both the board and management of Pemra ought to be augmented, aiming for regulatory excellence.

It is essential to ensure the agency strikes a balance between enforcing regulatory compliance and allowing for industry innovation and growth. Instead of constraining the media industry with excessive restrictions, it would be more beneficial to foster an environment that encourages experimentation and expansion. In this way, both the media industry and the public it serves can mutually benefit and evolve.

The integration of compliance and public disclosure, along with a well-rounded evaluation of new regulations, can significantly contribute to the growth and maturity of the media industry in Pakistan. By considering the broader societal impact and fostering a culture of transparency and accountability, the industry can overcome its current challenges and play a crucial role in Pakistan's democratic society.

Amir Jahangir is a global competitiveness, risk, and development expert. He can be reached at [email protected] and tweets at @amirjahangir

— Banner and thumbnail image by Hive Mind