Distaste of deportation kicks in as a kitchen café starts serving hope to Afghan women refugees

Food brings together these women and helps them defy stereotypical notions about Afghans in the city, who remain vulnerable and marginalised to date

In July 2004, a girl was born into an Uzbek-Afghan family in Karachi. The parents named her Wajiha. The little girl’s fate of being born in Pakistan was decided decades ago when her maternal grandparents traversed mountains and deserts, first in Uzbekistan, and then in Afghanistan with nothing but children in tow. Following their long and arduous journey, the family landed in the country’s largest, most densely populated cities that became home to numerous Afghan refugees who fled their motherland during the Soviet-Afghan war spanning almost a decade after the then superpower, the erstwhile USSR's, invasion of 1979.

Like many Afghan refugees, Wajiha’s family also settled in what is now a bustling part of the port city, known for providing shelter to the millions of migrants including her grandparents. Just like Wajiha, her mother, Masooma was also born in Karachi and was married young to her cousin, Jumma Khan, whose family arrived in the city several years later. The two built their lives here, raising six children including Wajiha — their second-born. This family, however, was blessed with one quality that made them stand out in the Afghan community — the skill to cook good food.

Both Masooma and her husband are excellent cooks. While Jumma Khan worked as a chef at a catering service, his wife was largely restricted to cooking at home. Soon this changed, as Masooma and her daughter Wajiha signed up for a culinary course at the Urban Cohesion Hub, a community centre for Afghan refugee women in Karachi. This centre gave the mother-daughter duo an opportunity to prove their mettle and use their culinary skills to empower themselves as well as other Afghan émigré women whom they met in this journey towards realising their dreams.

Cafe, a source of empowerment

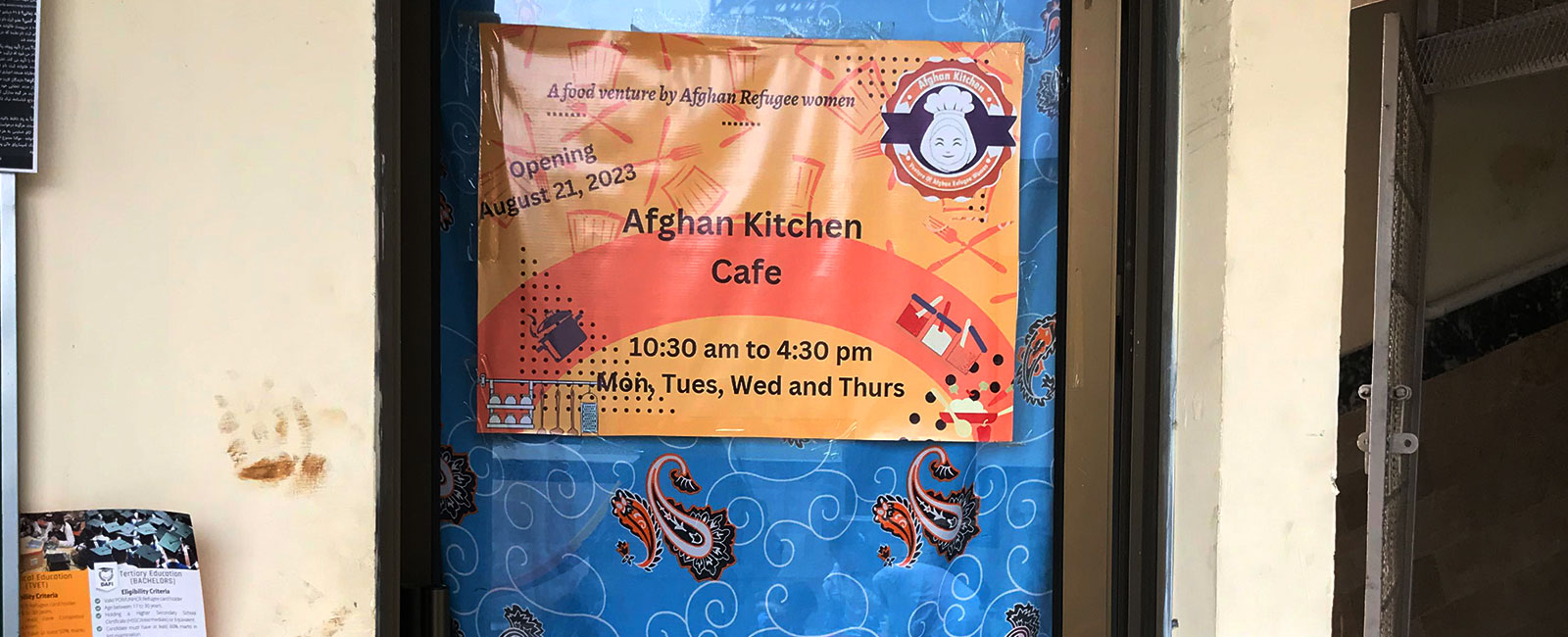

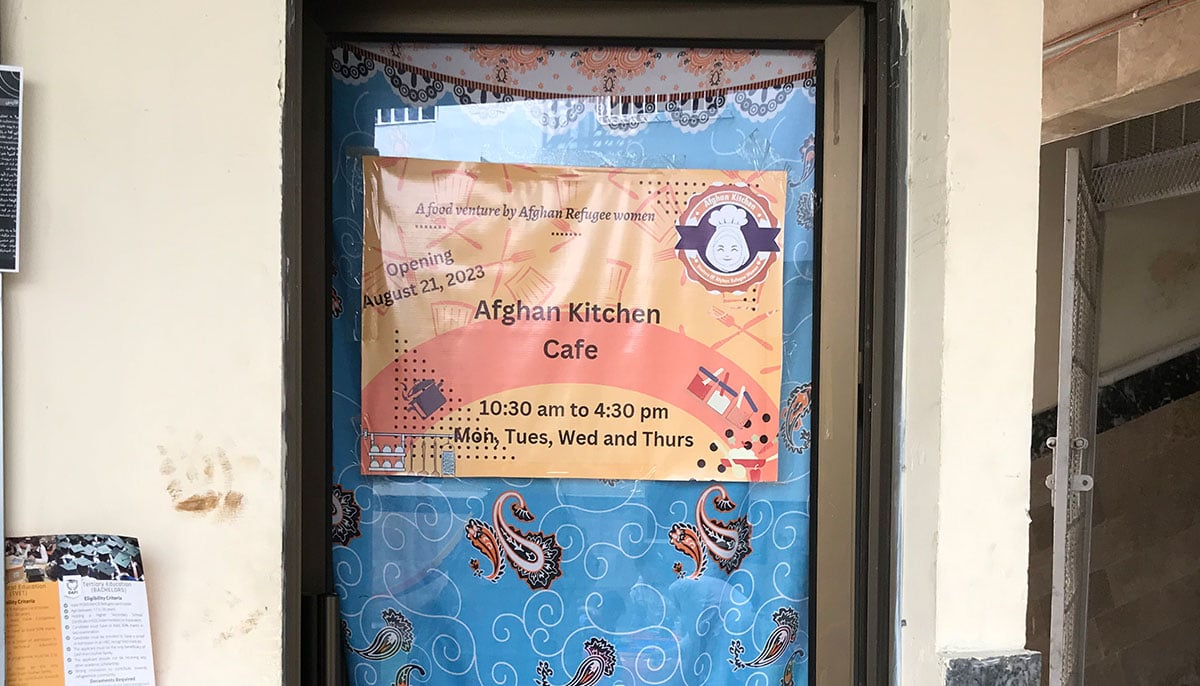

After months of excelling at the cooking course and rigorous training that followed at the Hub, this group of women together laid the foundation of the Afghan Kitchen Café offering Afghanistan’s authentic cuisine in Karachi.

“This café is a source of empowerment and special for us,” the 18-year-old Wajiha told Geo.tv, when we first met on a scorching October morning.

The teenager described the café as a safe space for Afghan refugee women who leave all their worries at home and arrive at the centre to not only cook but spend quality time with each other.

“Afghan Refugee women come here and spend their day doing something they enjoy. Owing to our conservative Afghan culture, the women usually do not get a chance to step out of their homes and work, but this café has provided them with that opportunity,” she added.

Wajiha, a student pursuing an intermediate degree in pre-medical, said it was her dream to become a chef and start her own business. This café was, therefore, her dream come true. Wajiha, her mother and a few other Afghan women are running this tiny café inside a community centre in Karachi. The women were first enrolled in a three-month cooking course and later underwent a six-month training to become professional chefs and restaurateurs, learning the tricks and ways to operate a food business. This months-long labour culminated in this small establishment where the women prepare authentic Afghan meals for their customers from across the city.

“After several months of hard work and training, we started this initiative less than two months ago in August,” Wajiha said.

The teenager is currently overseeing the kitchen’s operations with some help from the staff at the community centre. “I maintain the cafe’s accounts, do the costing and also calculate profit and loss. I also manage the customers, take orders from them and deal with the riders for food deliveries, as we deliver food outside the café too.”

Cooking Afghan delicacies

At the Afghan Kitchen Café, the mother-daughter pair is joined by two other émigré chefs — *Razia and Roshan. While the young Wajiha manages the finances and logistics of the café, the women stand by the stove cooking up delicious meals.

“In the café, I make Bolani, toast, biscuits, pulao and biryani among other things. I make both Afghani and Pakistani dishes,” said Masooma, whose sole purpose of stepping out of her house was to help her children receive education.

With nearly two months into business, this food venture by the refugee women is yet to make any significant profits, but they are hopeful for better days ahead. Wajiha receives orders through phone and Instagram messages. “We would get really little orders initially. But now the frequency has increased, so we’re hopeful that it will improve with time.”

At the moment, the café offers a modest variety of items on its menu such as snacks including Bolani (the Afghani version of aloo ka paratha), Mantu (a snack similar to momos or dumplings), samosas, biscuits and chai, while their lunch menu includes chicken biryani, channa pulao, Afghani beef pulao and chicken karahi. All their meals are offered with complimentary salad and raita.

Finding allyship, comfort in a safe space

It was food and cooking that brought together these women to kickstart this venture. But it also helped them defy the stereotypical notions about the Afghan community in the city who, even decades later, remain vulnerable and marginalised owing to the numerous challenges they face.

“Afghans were very illiterate at first and wouldn’t let the women step out of the house. But they now agree that everyone should be financially empowered,” said Masooma, who prepares delicious food in the café alongside her colleagues.

Masooma told Geo.tv that while her husband never stopped her from coming to the centre or running the café, it was the people around who gossiped about it. “I don’t care about it. I am doing this to empower myself financially and educate my children.”

Waheeda Ludin, a community liaison officer and an Afghan refugee herself, also said it wasn’t easy to convince women to come to the centre, as families from her community are known to be traditionalists.

“I’ve had to pay door-to-door visits to the community. A lot of social and community mobilisation was required to convince Afghan elders. Owing to the long-standing relationship and their trust, the centre was opened last year in May,” she said, informing Geo.tv about the centre’s inception and its role as a safe community space for Afghan refugee women, children and youth.

The community centre became a bustling space following word of mouth. All the women who come to the centre to learn different skills arrive after learning about it from their friends and neighbours in their neighbourhoods.

According to Waheeda, the café started in search of authentic Afghan cuisine which is something the Uzbek-Afghan community is famous for.

“I personally struggle with finding good Afghan cuisine. You will find it in Al-Asif Square but once you’re out of it, you won’t find it. The idea that there is a lack of Afghan cuisine led us to encourage these women to take this initiative, knowing that people will like it,” she said.

Waheeda shared that most women coming to the centre are from low-income backgrounds and the space was established to empower them. “As a community space, it has helped them improve their mental well-being. They feel better here, build friendships and share each other’s happiness and sorrows together.”

Roshan, a 37-year-old housemaker, also works as a chef in the kitchen and is excited to work alongside her fellow Afghan cuisine experts.

“We are fond of coming to the centre and want to move forward in life with the help of the café. We have been training to do this for the last six months and working in the café has given us a sense of financial empowerment,” she told Geo.tv.

Roshan and his family came to Pakistan from Afghanistan’s capital city, Kabul. “I was five when I came to Pakistan. All my four children —two sons and two daughters — were born here.”

Roshan does not only come to the centre to cook for the café but to also spend some quality time with her fellow chefs and find some comfort in each other’s company during difficult times. “Life can be difficult, so we come to forget about our worries. From 10am to 4pm, we cook and spend time with one another.”

The women cook together, comfort each other and exchange their mothers’ recipes with one another, while trying their hands at Pakistani cuisine as well.

Leaving friendships behind

Most of the women who come to the centre and even those in the café are registered Afghan refugees who possess the Proof of Registration (PoR) Card, an identity document that entitles them to legally stay in Pakistan. It is verified by the National Database and Registration Authority (Nadra). The card enables the refugees to open a bank account, rent a house and obtain a SIM card, among other things. Some possess the Afghan Citizenship Card (ACC), also issued by Nadra.

As I write this story, *Razia, one of the chefs in the café, has packed her bags to go back to Afghanistan, according to Wajiha. The 38-year-old mother of seven joined the café to earn for herself but was constantly worried about the looming fear of being asked to leave.

Her fears turned into reality after the Pakistani government announced the repatriation of all illegal migrants, giving them an ultimatum to leave by October 31. Today marks the last day for the deadline to end with over 3,000 Afghan families already set out for their motherland, according to the immigration officials at the Torkham border. Approximately, 1.33 million registered Afghan refugees in Pakistan hold PoR Cards, while 840,000 have the ACC, as per United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) data. The country, however, is home to more than 4 million migrants from Afghanistan.

The number of undocumented Afghan refugees, who are at risk of being deported by the Pakistani government stands at over 1.7 million. Many of these migrants are already en route to Afghanistan. While most arguments point to a systematic expulsion of Afghan migrants across the country, the Foreign Office, a day earlier, clarified that Pakistan was implementing its plan of repatriating “illegal foreigners” while exercising its “sovereign domestic laws”.

Upon her arrival in Pakistan, the chef in her late thirties received a token or case number to reside in Pakistan from the Society for Human Rights and Prisoners' Aid (SHARP), a non-governmental organisation working for Afghan refugees as a partner entity with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

When *Razia first applied to join the centre, she did not get through, but eventually made it on the second attempt after showing her Afghan identity card which she referred to as tazkira.

“I never thought that I would be running a café. We found out about it after our training ended. Everyone involved in this initiative was working hard to make this a reality and it left me hopeful that our hard work finally paid off after it started,” she said, speaking with Geo.tv in Dari, as Wajiha translated her words.

*Razia, her husband and children came to Pakistan three years ago from Afghanistan’s Baghlan province, soon after Kabul was taken over by the Taliban.

“We fled because of the intense conflict and Taliban’s takeover.”

*Razia, too, joined the café to earn a living after coming to Pakistan and enduring a lot of challenges. “But now that we’ve felt some sense of stability, the government is asking us to leave,” she lamented.

*Razia, who has been coming to the centre for almost a year now, is one of the many Afghan migrants who are leaving for Afghanistan despite their cases under consideration for legal residence in Pakistan. She also spoke about being asked to vacate the house her family was renting, while the men of her house were fired from their respective jobs. The kitchen, however, was her only hope in these difficult times.

“We really enjoyed learning during the course and had a good time with one another. The six months went by very smoothly, but now that we’re all set to apply all our learnings into the café, we’re being forced to leave,” *Razia complained.

Panic among Afghan community

Waheeda, a registered Afghan refugee herself, came to Pakistan from Kandahar when she was a six-month-old baby in the early nineties. She said the fear of being deported is not exclusive to those without documents in Pakistan.

“The atmosphere is full of panic right now. A lot of women have messaged me saying they are afraid to step out of their homes. There is a lot of anxiety,” she said.

Waheeda, a Pushtun-Afghan herself, said the ongoing crackdown against illegal migrants has left several Afghan refugee women worried and fearing for the safety of their families, despite being registered with the government. Their mental health has taken a toll, she added.

“Some women who came to me were in severe depression so much so much that I referred them to medical help. These women have come from well-to-do backgrounds, but everything changed for them all of a sudden after they migrated to Pakistan. On the other hand, the men get frustrated in such situations and resort to domestic violence, which also eventually affects children’s mental health,” Waheeda said.

Wajiha and her mother, too, have been stressed about the ongoing deportation of illegal migrants. The mother-daughter duo, both of whom were born in Pakistan, said they could not even imagine leaving the country as it was the only home they had ever known.

“We don’t face any issue due to the PoR Card, but we do feel afraid with all that is going on. We are more worried about being asked to vacate the house where we live,” the teenager said, sharing that a notice was handed out to their landlord by the police.

“When the landlord informed us about the notice, my heart was in my throat,” said Masooma, adding that he gave them an additional four months to stay in the house when she insisted he spare them owing to their PoR card.

“I was slightly relieved after this, as I don’t want to go to Afghanistan,” she said.

“We don’t know Afghanistan,” Wajiha chimed in.

Ever since the repatriation announcement was first made on October 3, the caretaker administrations in the centre and the provinces accelerated their actions against “illegal foreigners", tightening the noose around them as the deadline approached. The swift move by law enforcement agencies both in the federal and provincial territories left millions of migrants in the country doubtful about their status of residence, despite possessing appropriate documentation.

It is important to note that the government’s decision was closely linked with the increasing terror attacks in Pakistan, especially in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan provinces, as well as the escalating tension between Islamabad and the Taliban’s administration in Kabul.

Numerous human rights organisations including the United Nations have urged Pakistan to soften its stance on Afghan refugees, urging the government to allow them a voluntary exit and to avoid forceful, pressurised expulsion.

“These deportations violate Pakistan’s obligations as a party to the UN Convention Against Torture and under the customary international law principle of nonrefoulment – not to forcibly return people to countries where they face a clear risk of torture or other persecution,” the Human Rights Watch (HRW) said in a statement.

‘PoR, ACC cardholders won’t be affected’

After the announcement following the government’s apex committee meeting on the National Action Plan (NAP), the number of migrants who have left the country has increased, including those who are registered with Nadra. In its statement, the HRW said around 60,000 immigrants left Pakistan on October 15 following the government’s orders.

“About 87% of them, according to UNHCR and the International Organization for Migration, cited fear of arrest in Pakistan as their reason for going back,” it added.

The confusion around those being repatriated caused apprehension among migrants since the announcement. Abbas Khan, the chief commissioner for Afghan refugees in Pakistan, said the Commissionerate for Afghan Refugees issued a notification in this regard, clarifying that those with PoR Cards and ACC would not be affected by the new policy.

“They will remain living in Pakistan till the decision of the government. If those with PoR cards want to leave, it will be their own decision. We will not enforce it on them,” he said, speaking with Geo.tv.

Meanwhile, Caretaker Interior Minister Sarfraz Bugti — in an interview during Geo News' programme ‘Naya Pakistan’ — iterated that the expulsion of “aliens” would be conducted in phases with “illegal foreigners” to be sent back in the first phase. Bugti defined illegal as someone who does not have travel documents and has breached Nadra's records to identify as a Pakistani citizen. However, the minister also maintained that Afghan nationality card holders, POR cardholders and even the refugees registered with UNHCR will be repatriated in the second phase.

Nadra spokesperson, when contacted by Geo.tv for a comment on the matter, said: “Valid POR and ACC card holders are not a part of the illegal foreign nationals drive at this stage.”

Geo.tv also asked about the fate of refugees whose cards have not yet been renewed or remain unblocked, despite residing in Pakistan for two or more decades.

“The Government of Pakistan will make a subsequent announcement on the policy,” the spokesperson said when reached for comment in mid-October.

Zia Ur Rehman, a Karachi-based journalist who covers migration extensively, says that after the announcement of the November 1 deadline, Pakistan’s repatriation policy still remains vague with no clarity on who exactly is at risk of being sent back and who the government will take action against.

"In the initial stages, those with and without legal documents are being targeted in the crackdown," Rehman said, speaking with Geo.tv over a phone call. "However, after concerns were raised by refugee organisations and the international community, the government reassured that only refugees lacking legal documents would be arrested.”

Rehman said the primary forms of identification of registered Afghan refugees are the PoR and ACC cards. He questioned what would happen to these migrants if their cards were lost."Lawyers handling refugee cases have reported judges rejecting PoR cards that are expired, despite the government's notification not to harass individuals even if their PoR cards have expired."

The Commissionerate official, Khan, said he raised this issue around the lack of clarity, maintaining that those with PoR and ACC cards are residing in Pakistan under a legal agreement; therefore, they “can’t be repatriated”.

“There was confusion about it initially, which is why the provincial governments acted swiftly to make the repatriation effective. For instance, telling landlords that action will be taken against them if they rent their homes to those living illegally,” he said, informing Geo.tv about issuing a notification against harassment of PoR and ACC cardholders who, he said, will "not be repatriated".

“In fact, instances of harassment should be reported in such cases. Our Commissionerate in Sindh, headed by Hamood-ur-Rehman Mengal, can also be contacted in case these refugees are being harassed. We will look into it,” Khan reiterated, assuring even those with expired PoR cards to “not worry at all”.

Rehman, on the other hand, said the same confusion around the expulsion of migrants also surfaced at the time of establishing the now-defunct National Alien Registration Authority (NARA) in 2000, when the government was focused on identifying Bengali migrants. The body was merged with Nadra in September 2015.

The journalist highlighted that the government did not even count how many illegal and documented migrants were residing in Pakistan in the last census. “Had we done this, it would have been easier for the government to count and determine those residing legally and illegally.”

Several Afghan refugees and migrants who migrated following the Taliban’s return to Kabul in 2021 are worried about their future in Pakistan. Khan, however, insisted that there are different categories of those who arrived after the regime change.

“If anyone has a passport and visa, we are not repatriating them, even if they don’t have a PoR card. This drive is against those who don’t possess any document or those whose visas are expiring by the deadline issued by the government,” he said.

The government official said such migrants can have their visas renewed “as soon as possible if they want to prolong their stay”. He also noted migrants who came to Pakistan with plans to move to a third country and are registered with the UNHCR. They, too, are safe, he said, along with evacuated migrants who have served with the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) or other allied forces in Afghanistan.

“All of these will not be sent back upon showing their registration slip. But if they don’t possess any identification, have fake or expired documents, then they will probably be repatriated,” Khan asserted.

‘Political issue’

Moniza Kakar, a human rights lawyer who specialises in dealing with cases of Afghan refugees, termed repatriation of migrants a “political issue”.

“The government is doing this to divert the nation’s attention from actual issues such as the growing terrorism by Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and the rising inflation in the country. To do that, they chose to target the vulnerable Afghan community,” she said, in phone conversation with Geo.tv.

Kakar, who deals with multiple cases of Afghan refugees on a pro bono basis daily, added that 80% of migrants in the ongoing crackdown are cardholders.

“After arresting them, the police confiscate their cards, tear them apart and purposely lose them. These arrested people are not produced before the court,” she said, complaining that

During this period of crackdown, Kakar said, Nadra’s SMS service to verify the authenticity of refugees also stopped functioning. “The issue exacerbated anxiety among the refugees.”

Through the service, one could send an SMS mentioning the PoR card number 7000, which would then verify the details of the refugees and validate their registration with Nadra’s identification system.

Upon questioning Nadra and the Commissionerate about the problem being faced by refugees, the spokesperson of the government authority and commissioner said that the 7000 SMS service is “currently functional”.

“The verification facility is working for both PoR and ACC cardholders,” said Khan.

Shedding light on the legal aspects of the expulsion of the migrants and refugees in the context of Pakistan’s adherence to the international conventions and law, Kakar said: “While Pakistan is not a signatory to the United Nations refugee conventions or protocols of 1951, but we have signed other customary and international laws and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UNDHR), which bind us not to repatriate these migrants and refugees.

“The non-refoulement principle of customary law binds signatories to protect migrants who have left their country for safety from threats to their life due to war and politics. The country, where they have arrived by crossing the border with or without documents, is responsible to protect them and not deport them back to where they fled from.”

‘Pakistan, our only home’

Kakar said most of the Afghan migrants and refugees come from low-income backgrounds and remain vulnerable to persecution in Pakistan and Afghanistan if sent back.

“These migrants are oppressed and destitute, but hard working. It is important to see from where they have arrived from and in what situation. They fear being termed Pakistan’s spies if they go back. They are scared that the community in Afghanistan will also not accept them,” she said, stressing that these migrants have nothing to call their own in Afghanistan.

Kakar underscores that migrants who have received tokens upon their arrival in 2021 are the most vulnerable. “They are the ones who don’t want to go back and have fled to save their lives".

She insisted that this population of migrants, too, should be acknowledged as the token was given to them upon submitting initial documents and after being screened by the UNHCR and SHARP.

“This happens around the world where one seeks asylum or refuge. For instance, in the United States, if you apply for either asylum or citizenship, they give you document at the initial stage to help you survive in their country or work or conduct your business for as long as your application is in the process,” Kakar said, explaining the legal standing of migrants with tokens.

Kakar also pointed towards the incessant racial profiling of Afghans which, she laments, has penetrated the minds of the public.

Rehman, too, echoed her views, particularly with regard to Afghan refugees and migrants in Sindh.

“In the province, which is already plagued by ethnic tensions among various communities, there is an added layer of trouble for Afghans. Meanwhile, in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan, there is a majority of Pashtuns, so it’s not a big problem there,” he said.

The issue is so deep-seated that even Waheeda, an educated and relatively accomplished Afghan refugee, said she often feels ostracised and dejected by the situation.

“Even banks ask strange questions when Afghans go to open bank accounts and deny taking any responsibility. One can’t imagine what the underprivileged Afghans must be going through. They neither belong here nor there,” she complained.

Wajiha, on the other hand, remains resilient yet utterly despondent at the sudden turn of events.

“We cannot imagine leaving Pakistan. This is our only home,” she longingly declared.

Rabia Mushtaq is a staffer at Geo.tv. She posts @rabiamush

*Name of the subject changed to protect privacy