Why boys, who suffer sexual abuse, are told to man up and not stand up for themselves?

Ali, a 24-year-old entrepreneur from Hyderabad, narrating his painful ordeal of becoming a victim of sexual abuse as a child, said he was too young to even be aware of what was happening to him. It damaged him forever.

He spoke about the trauma he endured at the hands of his female tuition teacher at just nine years of age. “I am not comfortable in my own skin and feel dirty. I can't hug or even shake hands with anyone.”

Ali is in his mid-20s now but feels as helpless as that nine-year-old child he once was. His thoughts, as he sits on his rooftop every night while recalling the suffering, are often suicidal.

“I’ve become an insomniac; darkness haunts me.”

The young man revealed he was “brutally raped” by the tuition teacher, thinking that she was just punishing him for not being a very bright student.

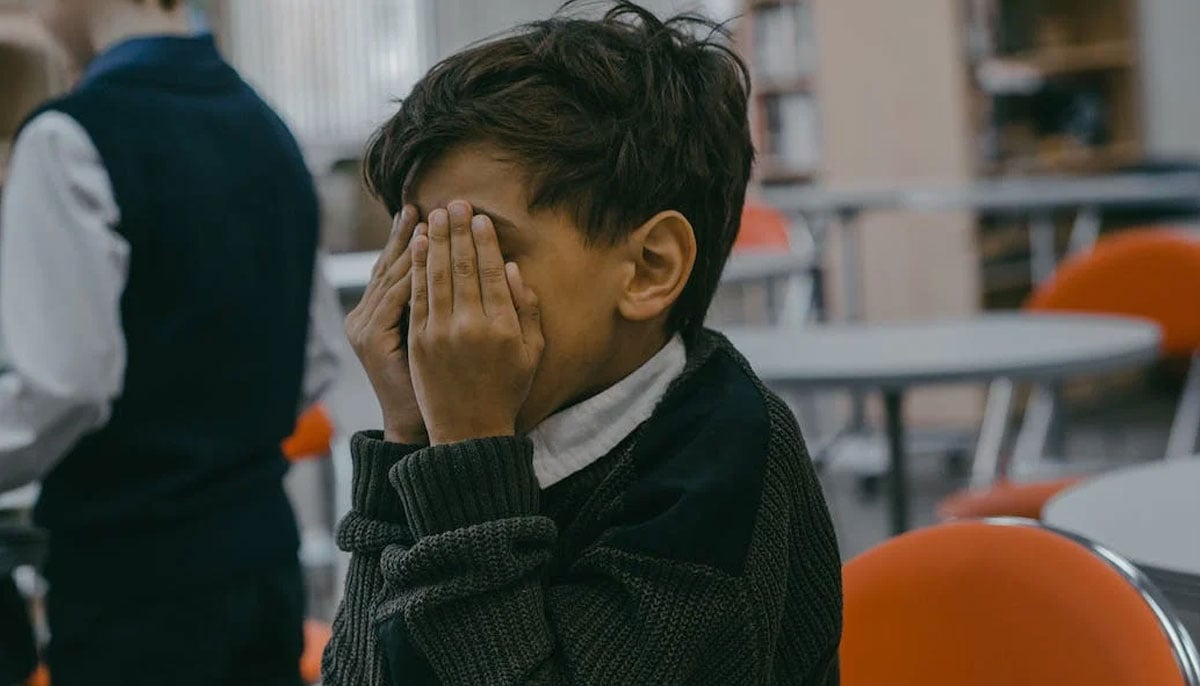

Discussions of sexual abuse, especially in the case of young and grown-up males, are often hushed up and brushed under the rug in our society. The struggle of male survivors remains largely invisible with toxic masculinity ingrained from a young age, men are conditioned to believe that they must always be strong, impervious to pain, and devoid of vulnerability. These societal norms stifle their voices and force them to endure their agony in solitary anguish.

In a country where boys are raised to suppress their emotions and never show vulnerability, the staggering truth remains obscured. According to a recent report by Sahil, a non-profit organisation advocating for the protection of children, an average of 12 children face sexual abuse every day in Pakistan. Shockingly, the report titled 'Six Months Cruel Numbers 2023’ reveals that the proportion of boys was 10% higher than girls, around 593 boys and 457 girls aged 6 to 15 years were victims of sexual abuse.

‘Pushed into isolation’

Saad, a university student in Karachi, recalled how, at the tender age of seven, he was subjected to heinous acts by a man from his neighbourhood bakery. "I started isolating myself and stopped talking to anyone. I still can't get myself to go out in crowds and have major anger issues. My mom thought I was only refusing to go out because I was introverted," he said, sharing his ordeal with me.

His ordeal lasted for three months and despite his attempts to confide in his family, his cries for help fell on deaf ears. “No one ever questioned why I had such a drastic change in my behaviour.”

Another survivor added that he attempted to confide in his friends, however, "they laughed at and mocked me. I was not old enough to comprehend what was going on.”

The repercussions of such trauma often lead to long-term psychological disorders, with a staggering 82% of male survivors experiencing at least one psychiatric disorder, as mentioned in data gathered by the National Comorbidity Survey, a United States-based survey on psychiatric disorders. Unfortunately, the lack of research and support for male sexual abuse survivors in our country exacerbates their plight, leaving them isolated and struggling to cope with their inner demons.

On the other hand, Zaki — a 21-year-old survivor from Jeddah — shed light on the cultural notion of power and misogyny.

"I grew up in Jeddah, I was abused thrice there, each time by Pakistani men. I still remember the faces of my abusers and the smiles on their faces. Every single time I'd see the power growing in them – I could tell they thought ‘I'm a man, I have all the power’ visible on their faces."

Talking about how societal expectations contribute to the creation of individuals devoid of empathy, he added: "The misogyny in our country is so deeply rooted that we end up creating monsters with no feelings in the name of 'man'."

And if someone ever talks vulnerably about their traumas, they are expected to "shut up and man up".

‘Never taught about consent’

"I was only in grade six and was not aware of what was happening to me. When I realised what it was growing up, I got revengeful and frustrated. I have never been able to talk to my family about it, and I stopped going to madrasahs." shared Mohsin, a young man from Sakrand, Sindh, who detailed his harrowing experience with the neighbourhood mosque's prayer leader.

"He’d drag me to an empty room of the mosque. I was under the impression that I was his favourite student and he was appreciating me."

Mohsin added he was never taught about consent or bad touches as it is considered to be an awkward topic in our culture. He revealed that his abuser is "still the prayer leader of the mosque even after a CSA case investigation was held against him."

Children in our society do not receive education about the distinctions between good and bad touch. This topic remains a forbidden subject, with cultural concepts such as ‘sharam’ (shame) and ‘haya’ (modesty) preventing parents from imparting the necessary knowledge to protect their children from enduring long-term psychological harm.

Tragically, the pervasive notion of masculinity in Pakistani society further complicates the issue, perpetuating a cycle of abuse and silence.

Alarming cases

For over a decade now, particularly with the expansion of traditional and social media, reports of child sexual abuse have witnessed an increase. Some of the incidents reported last year, including those involving young male victims raise alarms with regards to the worsening situation.

On December 19, a teenage boy was raped and murdered in Tando Muhammad Khan. Following an initial investigation, police reported medical professionals confirming the horrifying details of the crime.

Similarly, on June 21 in Lahore, a minor boy was allegedly subjected to sexual assault and then thrown from the rooftop of a madrassah in the Raiwind area. Suffering from severe head injuries and bone fractures, the boy fought for his life for 10 days but couldn’t survive.

Dismaying data

Furthermore, In 2021, the country witnessed a concerning rise in child abuse cases, totalling 3,852, reflecting a 30 % increase from 2020. These cases encompassed child sexual abuse, abduction, missing children, and child marriages, averaging over ten daily incidents.

The gender distribution revealed 54 % girls and 46 % boys as victims, with acquaintances, family members, strangers, and women abettors identified as primary abusers.

Notably, cases involving the latter group surged from 29 in 2020 to 86 in 2021 while Punjab stood out with the highest reported cases.

In 2022, the situation worsened, with 4253 reported cases, a 33 % spike from the previous year.

The daily average of more than 12 abused children persisted, and the gender divide showed 55 % girls and 45 % boys as victims.

The age group most vulnerable was 6-15 years, with a higher number of boys than girls affected.

Acquaintances remained the leading abusers and women abettors with an 8 % increase in involvement in 2022.

Punjab continued to have the highest reported cases, while other provinces also documented instances of child abuse.

Sahil Executive Director Manizeh Bano classified the statistics about cases of abduction, early marriages and missing children.

"In our society, boys have generally been at most risk as people are usually protective of their girls; whereas, no one asks a boy (irrespective of the age) where he’s off to," she said.

She further explained how police officials are judged by two major criteria — the crime rate and the number of solved cases in their territory — which leads to reluctance in reporting missing children cases for the first few days. Especially when it comes to a missing boy, officials usually assume that the kid could’ve wandered off somewhere. However, the increase in reported cases indicates a shift toward taking such cases more seriously, by both the officials and families.

These statistics and insights by Manizeh reveal the alarming prevalence of sexual abuse and the societal dynamics that contribute to underreporting and delayed responses.

Societal stigma and mental health

Mehwish Khan, assistant director and stress counsellor at the Federal Investigation Agency’s (FIA) Cybercrime wing, addressed the stigma surrounding male survivors, emphasising the societal challenges they face when sharing their experiences.

"In a household, parents are usually scared to get labelled by society and subsequently hush their kids. Additionally, if a man opens up in his social group, he is made fun of and laughed at by his peers. Usually surrounded by comments like 'man up' or 'you must be enjoying it.'"

In comparison to men, Mehwish said, "Women tend to talk about their abuse, one way or the other — either with a friend, partner, or their family — women in our society are allowed to be more vulnerable and emotionally available, whereas by forcing men to ‘stay strong’ we as a society take away their right to express themselves."

"Child abuse isn’t a kind of trauma that can be fixed in itself — even if someone manages to let go of their trauma they surely either face difficulty in maintaining future relationships or deal with certain medical conditions like anxiety, depression or anger issues. It can’t be fixed by mere self-help issues books instead requires the help of a professional," she added.

Furthermore, parents must educate their kids about “consent” said Mehwish, adding that “you shouldn’t force your kids to shake hands or hug people if they don’t want to and you must respect their consent to teach them to respect others.”

"If a child opens up to their parent about being abused, they must keep their calm and make sure to make their kid feel safe in its space and to get him away from the situation. The priority should be the kid's mental health."

Similarly, Manizeh mentioned, "the worst kind of result of CSA is when the abuse goes on for a long period of time – neglect and the frustration built inside the child could result in the child following his abusers' patterns."

In the profound narratives shared by male survivors of childhood sexual abuse, a courageous movement emerges — one that aims to shatter the long-standing silence encasing this deeply sensitive issue — as we grapple with the realisation that secrecy and shame have long been accomplices to the perpetuation of abuse.

Breaking the silence is not merely a step toward individual healing; it is a collective responsibility to unravel the systemic structures that enable abuse to thrive.

To understand government policies and the role of human rights commissions for the redressal of child sexual abuse in Pakistan, particularly those established to address child rights, the chairperson of the National Commission on The Rights of Child (NCRC) was repeatedly contacted but did not respond to the request for comment.

The narratives shared in this piece serve as catalysts for societal transformation, pushing for an environment where survivors are not only heard and believed but also offered vital resources for their recovery journey. It is a plea for empathy and understanding, contrasting starkly with the silence that has allowed abuse to persist unchecked.

*Names of victims have been changed to protect their identity.

Muqaddas Fatima is a media student with an interest in human rights and social activism. This article is derived from her thesis on male child sexual abuse.

— Header and banner design by Freepik