Cities: too hot to handle

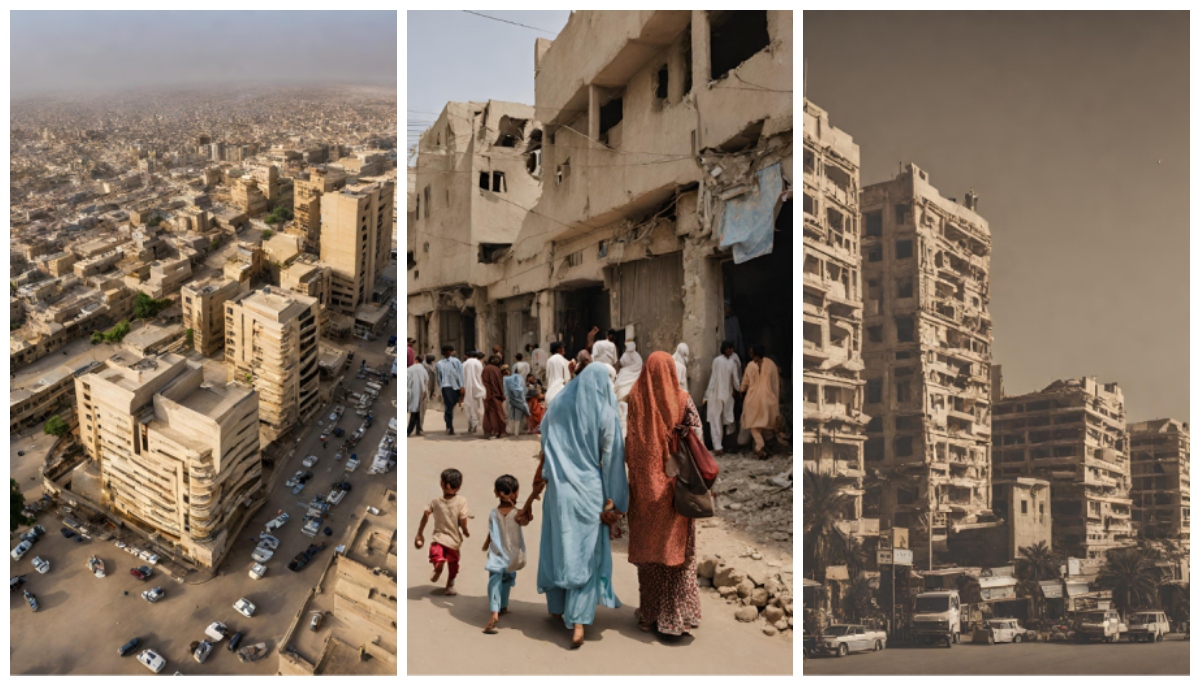

Urban heat island effect is usually defined as phenomenon when metropolitan area is warmer than rural/suburban surrounding area

The United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres painted a terrifying picture of roasting earth now that the "era of global warming" has ended, replaced by the "era of global boiling" with "children swept away by monsoon rains, families running from the flames (and) workers collapsing in scorching heat".

The common refrain that the summer of 2023 was a "hellish" one is no exaggeration and is backed by science. Climate monitoring organisations like the European Union's Copernicus Climate Change Service, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NAOO) and NASA confirmed that July 2023 was the hottest month globally in more than a hundred years.

Sheetal Vishal, 33, complained her kitchen turns into a bhatti (furnace) in summer. She said that the heat becomes unbearable when there is no electricity when she lives in Shirin Jinnah Colony, one of Karachi's informal settlements. "This summer, we had intermittent power for 12 24 hours. It gets so stifling at times, I must get out of my house and onto the road just to catch my breath," she said.

This is the perfect example of the urban heat island (UHI) effect. It is usually defined as a phenomenon when the metropolitan area is warmer than the rural/suburban surrounding area.

The heat is created by urban density — many people are packed in small, congested spaces; buildings, including homes and shops, are constructed close together and made of material that traps heat. With so much energy generated, it has nowhere to go, and thus it lingers on.

Dr Ghulam Rasool, who heads the Climate Change programme at the International Union for Conservation of Nature, pointed to Pakistan's "runway population" of over 240 million, which he said was the root cause of all its problems, including the UHI. The more people living in crowded, khichri-like neighbourhoods, which lack proper sewage systems, sanitation and water, the more volume there will be of "air pollution, vehicular emissions and waste burning", the three culprits that lead to UHI in cities.

Working in her room cooped up without a fan is not easy for Kainat Naz, 26, referring to long hours of power outages. Living in Orangi Town's Hanifabad neighbourhood and working remotely for a foreign IT company as a manager, she pointed out that going out into the courtyard does not help. "Along with lack of ventilation, there is too much background noise for me to participate in a conference call," she said irritably.

"We share a common wall with our neighbours and can pretty much hear what is happening next door," she explained, adding: "I often miss my previous workplace that was air-conditioned, peaceful and quiet," she admitted.

When Vishal and her husband moved to their new home near Clifton Beach, she looked forward to enjoying the cool sea breeze. Instead, she was shocked to learn that multistorey flats surrounded her two-room home on all three sides. "It is unfortunate that we are so close to the sea and yet get no breeze at all," she rued.

Like Naz, Vishal said they shared common walls on both sides with their neighbours, so there are no windows. They have a window on the rear, but if they open it, it will mean peeping right into someone's home.

The UHI effect glaringly showcases the inequitable impacts of urban heat. Lower-income settlements and communities are usually the most vulnerable to heat and its consequences. They are also the least likely to be able to afford ways to keep cool.

That is why Islamabad-based climate expert Fahad Saeed is in favour of developing "intermediate cities" to reduce the migration of people to big cities, contain the urban sprawl, and reduce the densification of cities to lessen the UHI effect. Although cities were the biggest emitters of greenhouse gases, Saeed said care should be taken to equate UHI to the rise in global temperature.

It has also been observed that Karachi's famed "thandi shaamein" is getting scarcer. A recent research by the Karachi Urban Lab (KUL) found that over the past 60 years, Karachi's daytime temperatures have risen by 1.6 degrees Celsius and nighttime by 2.4°C. Dr Nausheen H Anwar, director of the Karachi Urban Lab at the Institute of Business Administration, links the rise in nighttime temperatures to the UHI. "The high-rises, footpaths, even asphalt roads, trap the heat coming from the ground from dissipating into the atmosphere", she said.

Ranked among the world's least liveable cities on The Global Liveability Index 2023, published by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), Karachi, with a much-disputed population figure of over 18.61 million (and which has been challenged in the court), has been put at the bottom fifth at number 169 out of 173 cities. According to the World Bank, 50% of the city residents live in informal settlements.

That our cities are getting hotter is stating the obvious. "Not enough green spaces, more smoke-emitting vehicles because of a lack of proper public transport system, poorly designed buildings without cross ventilation and with materials that absorb heat and therefore rely on excessive use of energy for cooling" are some of the reasons given by Tofiq Pasha, a social and environmental activist.

Unlike Vishal and Naz, Pasha's "immediate neighbours" are trees, which explains why his home is a cool haven even in Karachi's scorching summer months. "God, I am blessed!" he counts his good fortune, and this hits home every time he returns from the stifling, congested, concretised city.

Happily ensconced in over a hundred trees, with some as old as the 250-year-old massive Ber tree over 3.5 acres of farmland, the trees provide shade to the house through the day and keep the inside of his house cool. Additionally, it is also the sea breeze in his area that circulated.

He blamed the "rows of conocarpus" along roads and streets in Karachi's different neighbourhoods, from ground to 30 feet high", which act as a wall to block the breeze and the poorly designed high-rises dotting the city that radiate heat" for heating the city.

That is why, said Dr Noman Ahmed, the head of the Architecture and Management Sciences at the NED University of Engineering and Technology in Karachi, road medians should have carefully chosen "low maintenance local trees, with adequate diversity and a capacity to generate oxygen" and planted scientifically. He also suggested including urban forests and wetlands in a city's landscape planning exercise.

Dr Ahmed said it was important to alter the existing approach to design. "Urban design as a field of expertise is absent from the transportation infrastructure, he said, adding: "We need to retrofit the existing traffic intersections and traffic jam locations to come up with tailormade and specific solutions" and gave the example of how in a paved and asphalted surface, a vertical landscaping plan can be included to insert plants, foliage, and other green elements. The UHI moment for him was back in the 1980s as a student. "As a college student, I often went to the last stop of public buses where many public buses would wait for their turn to move, keeping their engines idling since fuel was cheap. I could feel an awful amount of heat, greater than the day temperature around those corners."

But on hot summer days, the temperature in Karachi can rise to 40°C. The media will warn of an eminent heatwave if the phenomenon continues for a few days. For those living in a flat in one of the high-rises in the more congested areas of, say, Karachi's Gulshan districts, the 'feel like' temperature can be as high as 44°C, with people experiencing exhaustion and breathlessness, especially without air conditioning. On the other hand, Sixty-four-year-old Pasha can ride it out on his farm as "even in the middle of the day, on the hottest of days", he is saved by the greenery around him.

With the city dotted with poorly constructed high-rises, Pasha said, the buildings absorbed huge amounts of heat. "Touch the walls of the interior of a building which has no air-conditioning, and you will find it radiating heat," he said.

When the city is boiling, it needs more energy, which often results in power outages as utility companies do not have enough energy, as Vishal and Naz experienced. And the hotter it gets, the more air-conditioners are needed. Refrigeration and air conditioning account for around 10 per cent of greenhouse gas emissions – three times more than aviation and shipping combined. Ironically, the appliances that keep us cool are warming the world.

Asif Ali Ansari, 40, who has been repairing refrigerators and air-conditioners for the last 20 years, has seen how the use of air conditioners (ACs) has increased over the years, which has boosted his work. "When I started, I had a friend who helped me. We have hired three more people, and our work never gets done." While offices and homes of the rich always had ACs, Ansari said there is at least one AC in every "middle-class home".

But Pasha rarely turns on the air conditioning. "I have a pedestal fan, always kept on a slower speed, that stands by one of the windows, and it draws in the cool breeze," he explained. He has windows on three sides of his bedroom, and the fourth wall is a door that is always open, providing good cross ventilation," he added.

Those who have roof gardens say they experience their homes to be cooler than their next-door neighbours. Aftab Karimjee, who lives in Karachi's Shabbirabad neighbourhood, has invested in a green roof. Some ten years ago, the 66-year-old apparel manufacturer started gardening on his rooftop as a hobby. "I immediately realised that the first floor, where I have my bedroom, which would be like an inferno on the hottest summer days, with the mercury rising to 40°C, became considerably cooler." Over the years, he covered the entire roof and felt he did not have to turn on the air conditioning during summer afternoons. A year ago, he started experimenting with the hydroponic system, and the vegetation became thicker and denser. "The temperature on the first floor has gone down further and, by a conservative estimate, must be at least five degrees lower, if not more," said Karimjee. Their ground floor section, he said, is even cooler than the first floor.

Rethinking urban planning

Two years since Yasmeen Lari gave the Denso Hall area a facelift, temperatures in the area have come down, and it has not suffered urban flooding. A veritable walking oasis today, in the old, congested quarters of Karachi, the octogenarian architect, also Pakistan's first woman architect, believes the only way to make our cities liveable is to de-carbonise the environment and suggests some inexpensive and comparatively simple ways to achieve that. Lari says there should be limited vehicular traffic to certain roads to reduce fumes, creating as many walking streets as possible with lush planting, trees that provide shade and improved biodiversity to clean the air and cool the environment.

She suggests removing all pavers from the medians. "Make them as wide as possible to plant shady trees and native flowering bushes in between. She also says that concrete pavements to surfaces are "impervious and continue to absorb and emit heat, warming the atmosphere. Terracotta has been tested to be permeable; it retains water, and as it evaporates, it cools the air."

The proliferation of plantations, especially this architectural feature known as vertical gardens or plant walls, can grow just about anywhere, but if done carefully with plants that absorb air pollutants best, it can play an essential role in bringing the temperature down by several degrees to mitigate the UHI effect.

A ban should be imposed on constructing multistorey buildings, says Lari, as they are a source of heat-emitting facades, warming the atmosphere and blocking cool sea breezes. "Heritage buildings had open spaces and courtyards attached to them, which would have trees growing. The city is losing its original character and valuable greenery and spaces with their destruction." By retrofitting or reusing already built buildings, further construction can be prevented. "Newer buildings mean more carbon emissions and greater the waste stream along with extra heat being generated and greater water consumption too."

According to Lari, it is time to revisit the drainage system that the city is governed by and is a legacy of the British. "We are constantly told by experts that the nullahs – either encroached or full of garbage – must be cleared to make way for rainwater to flow freely into the sea. In my view, we should conserve every drop of water rather than disposing it off into the sea; hence the necessity of decolonising our antiquated systems," she argues.

She wants nullahs to become green forested spines running through the city where fruit trees and flowering trees grow, which can be turned into places for recreation and where women from neighbouring areas can tend to their patches of kitchen gardens, thus encouraging food security. At the same time, these can become aquifer trenches to absorb enormous quantities of flood waters to replenish the groundwater.

"Instead of draining the rainwater to sea through drains and nullahs, absorb the water into soil and aquifer wells to make soil more fertile that will support more vegetation and prevent urban flooding," she concludes.

Zofeen Ebrahim is an independent journalist. She posts @zofeen28

This article was originally published in the Lok Sujag. It has been reproduced on Geo.tv with permission.