Where are women in the big picture?

Despite the male-dominated environment, women persist in their efforts to explore and assert their identities within the urban landscape

As I walked through the lush green and extensive Frere Hall gardens, sunlight sieving through tree leaves lit the pavement. I walked a few more steps as I tried to absorb the grandeur of the resilient colonial building. I looked to my side, the benches lining the edge of the garden were occupied by men sleeping across, some of them smoking, or comfortably seated and engrossed in their surroundings. It was late afternoon and the sun moved behind the Frere Hall building and lit up its angular structure in a warm gold hue.

As I moved further along the pavement, I came across male food vendors selling sodas, roasted corn, ice cream, and French fries bordered along the entrance of the Hall. Towards the pavement right across the Art Gallery’s entrance, were a group of male and female protestors raising awareness about child abuse with camera shutters and chants filling in the densely polluted air.

I moved towards the library and observed large sums of men — young boys, elderly, and middle-aged engaging in various activities: shooting TikTok videos, playing a game of cricket, skating, or just having a chat. As the Saturday sky became duskier, women started appearing in the back gardens with their family members, an area adjacent to the playground. My observations of the Hall led me to a pertinent question — where are the Women?

According to Arif Hasan, a veteran architect and urban planner, post-partition Pakistan initially adhered to conservative values, restricting women to their households. However, a post-colonial generation emerged, advocating for a more liberal Karachi: casinos, nightclubs and bars sprung open across the streets of Karachi.

The 1980s, under Ziaul Haq's rule, saw gender-based discrimination, with the introduction of Hudood Ordinances reinforcing women's inferior status and restricting their roles.

Despite these challenges, the 1990s witnessed women negotiating their societal roles, and today's generation of women actively participates in various public spheres, challenging patriarchal norms. The politicisation of women's access to public spaces, often weaponised through religion, remains a significant barrier to overcoming entrenched gender inequalities. Hence, public spaces like Frere Hall continue to represent this disparity.

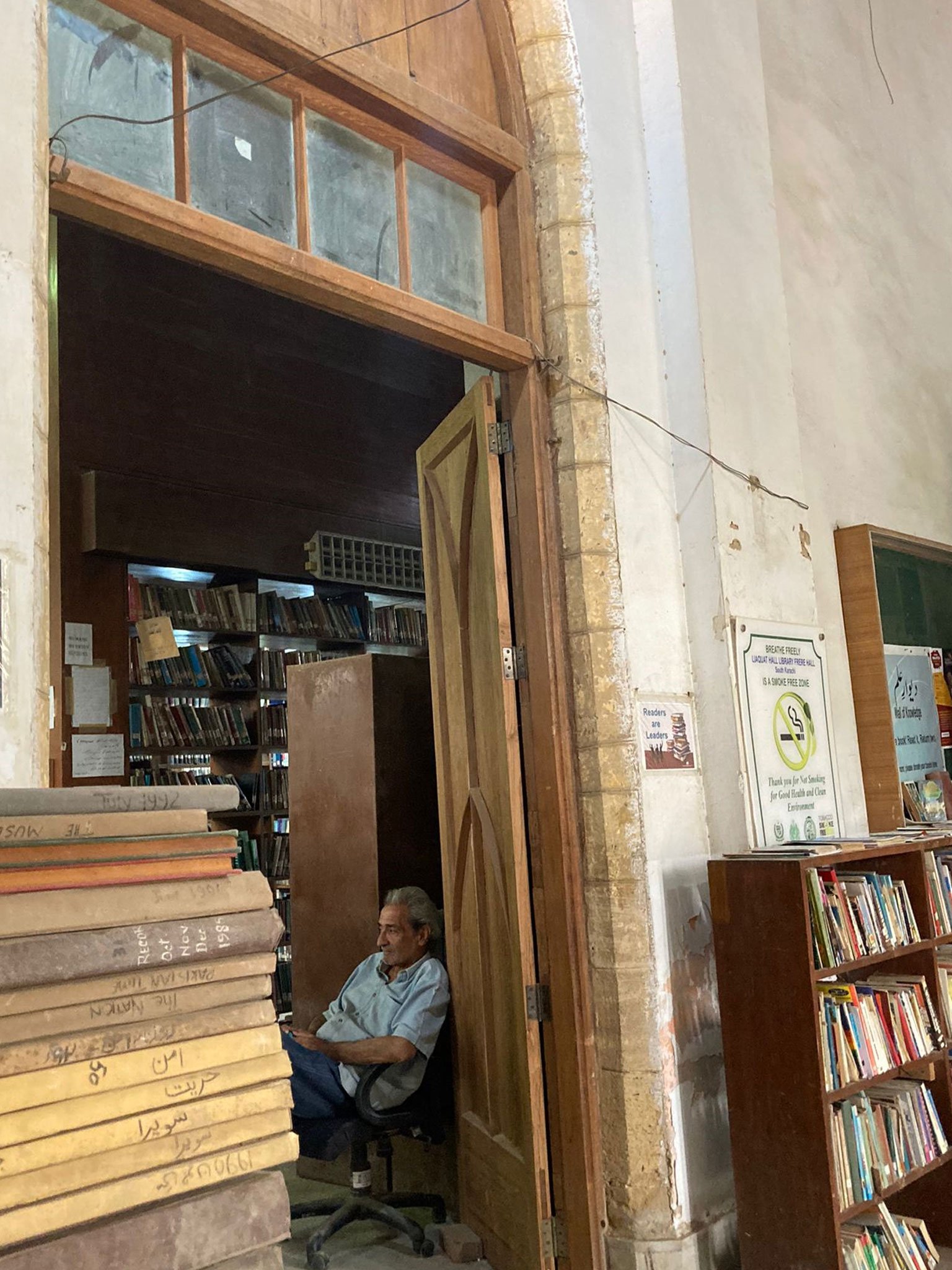

My recent visit to Frere Hall was on a weekday. Behind the fencing of food vendors lining the road — a city warden dressed in an olive grey uniform accompanied me to the Art Gallery and Library within the Hall. He explained that the government facilitates students with classes for the preparation of the Central Superior Services (CSS) examination free of cost.

Explaining how the city government is invested in these students’ well-being, “people’s privacy is of utmost importance here, whoever comes here is safe". There is a separate section in the library for female students, male students are not allowed over there,” he said. The necessity for distinct spaces for men and women elucidates that the two genders undergo differentiated treatment within the city.

Recent policy reforms like the National Gender Policy Framework 2022 and the establishment of Gender-Based Violence (GBV) courts reflect a commitment to gender equality. However, the National Report on The Status of Women in Pakistan, 2023, points out persistent structural and socio-cultural barriers, with a highly patriarchal society and regressive norms contributing to discrimination and violence against women.

Similarly, The UN's 2020 Women Safety Audit found that 80% of Pakistani women experienced harassment in public spaces, with 90.3% not considering it a crime due to familiarity. These alarming statistics shed light on the challenges women face in public spaces, contributing to the male dominance seen in places like Frere Hall.

Accompanied by the warden, I strolled through the library. The tall shelves were full of dust-ridden books due to the ongoing restoration of the Hall. Towards the end of the library is a female section where female students huddle around a table and prepare for their exams. An air cooler beside the table fans the moist heat away as students whisper course material to themselves while attempting to memorise it.

A burka-clad female student tells her group of friends that she needs a break after long study hours. She believes it is a misfortune that a city as populated as Karachi lacks public spaces that are safe for women. Regardless, she is grateful that Frere Hall has useful archival material and books, a peaceful environment which improves efficiency while studying, and a separate section for female students — a basic facility that she yearns for.

“I come all the way from Korangi to attend classes and study in the library using books, newspapers, and other archival material. We spend more time studying here compared to our homes. I have always felt safe - I have never had a problem within the library."

The issue of accessing public spaces is intricately linked to class, gender, and ethnicity. According to Hasan, the working class faces restricted access as public spaces are predominantly shaped by the elite, leading to an "anti-poor bias" in planning.

Sana Rizwan, an urban and environment planner, emphasises the need for a participatory approach in designing Karachi's Masterplan, addressing the citizen's demands, and bridging the gap in provided facilities.

The senior architect notes a gradual decline in the influence of Zia's policies, highlighting women's efforts in reclaiming public spaces. He cites a survey indicating women's preferences for parks, emphasising the need for change, even if the initial shift is within the elite class. The varied experiences of working and upper-class women in Frere Hall highlight the diverse interactions women from different backgrounds have with public spaces.

A 25-year-old female student currently doing her master's in psychology has visited Frere Hall multiple times. “Public spaces are the spaces where you can indulge in a different aspect of yourself. You get the opportunity to be genuinely stress-free. When you are outside you can see the sky and breathe in fresh air. Maybe, you have a purpose, but you can also be devoid of purpose and that is when you truly be yourself,” she said explaining an individual’s need for public avenues.

According to her, she does not feel safe in and around Frere Hall. She is repeatedly confronted with the need to stay near the swings where there are women and families. Based on her experience, when there are no classes, the library is highly male-dominated, which makes her feel like she would not be able to reach out to anyone for help in case something unexpected happens.

In her book, Why Loiter?: Women And Risk On Mumbai Streets, Shilpa Phadke writes: “Risk taking is often considered acceptable, even desirable masculine behaviour. For women, on the other hand, it is not only seen as unfeminine, but as potentially the behavior of a ‘loose’ woman. Turning the safety argument on its head, we now propose that what women need in order to maximise their access to public space as citizens is not greater surveillance or protectionism (however well meaning), but the right to take risks."

Her argument aptly describes the change in dynamics that has helped women in Pakistan raise a voice for themselves, motivating them to overcome their fears and take risks in expanding the limits imposed on them.

It is significant to note that women do not occupy a passive role in this regard, on the contrary, Pakistani women have made immense contributions to change how their realities unfold. In September 1981, a group of women convened in Karachi to resist the detrimental impacts of martial law and the Islamisation campaign on women.

United in their quest for freedom, they formed the Women's Action Forum (WAF), the first comprehensive national women's movement in Pakistan. By organising demonstrations on the streets and advocating against the Hudood Ordinances and the Law of Evidence, WAF emerged as a prominent force in opposition to Zia's patriarchal regime.

Non-governmental endeavours such as the #girlsatdhabas hashtag’s conversion into a nationwide phenomenon in 2015 for seeking female representation in public spaces reflect that this resistance towards this issue was a widespread sentiment among women.

Explaining her motivation behind what converted into a collective online campaign, Sadia Khatri adds, "It isn’t like dhabas and other public sites specifically say ‘Women not allowed’ and it isn’t like once a woman is there (usually with her family or husband or male chaperon) she is made to feel uncomfortable, but and the way men outnumber women in public spaces says a lot. The disproportion is outrageous, even disturbing."

Shaheen Nauman, the tour guide for the Karachi Heritage Walk headed by the Pakistan Chowk Community Center (PCCC), is one of the pioneering women in Pakistan leading historical tours. Nauman has invested a significant part of her life in solo exploration, delving into the intricate histories and narratives of Old Town Karachi. Her presence and expertise amplify the presence of women in public spaces, breaking barriers, and opening avenues for others to follow. Through her lens, the old town becomes a means to exemplify the power of reclaiming public spaces.

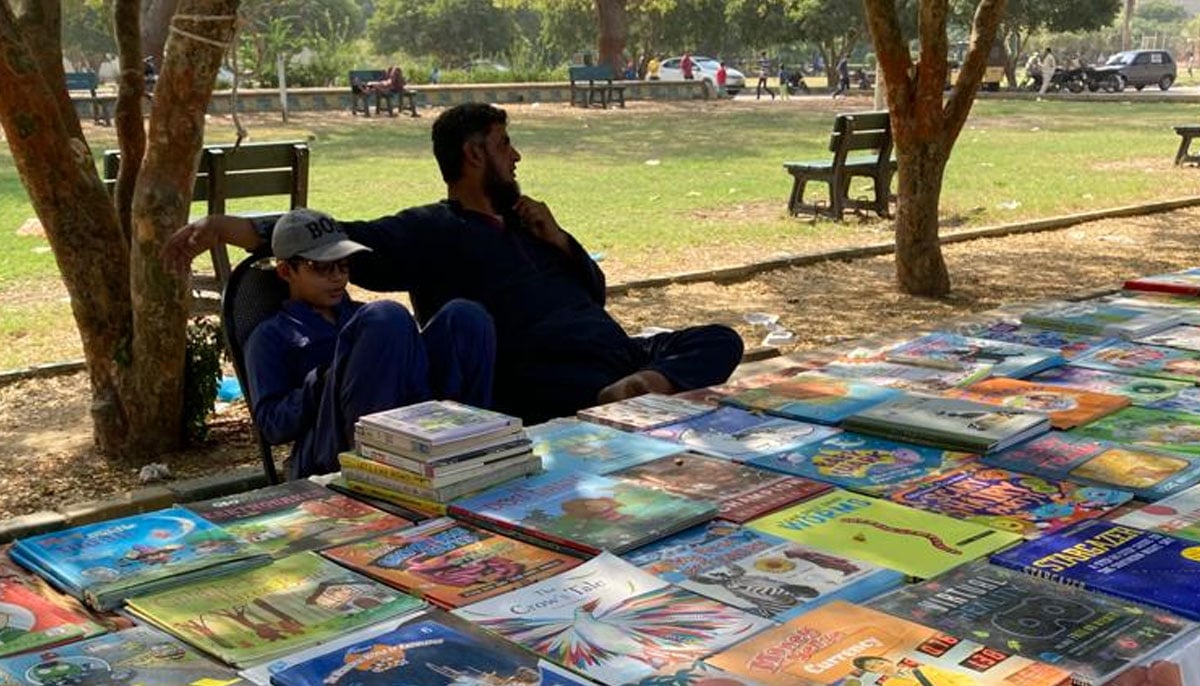

Various visuals from Frere Hall narrate a tale of female resistance to a male-dominant space. Working-class women often visit the hall as a means of escaping their monotonous daily lives, as narrated by Chandni, a petite, dusky-skinned young girl unable to speak Urdu fluently, who often visits the hall on Sundays with her partner to enjoy food and fresh air. Women also bring their children to an open space where the latter can play and interact with others while they sit on a bench to enjoy fresh air.

Upper and middle-class women are often seen buying books from the Sunday Book Fair, visiting the Liaquat National Library and Sadequain Art Gallery for recreational purposes, and using the garden space for protests. Frere Hall accommodates a diverse range of individuals with varied interests and needs, which is why it remains a magnet for people from different societal segments. This diversity plays a role in determining whether specific groups of women perceive the space as safe or not.

Due to its ability to house large crowds and its close vicinity to the Karachi Press Club, Karachiites have repeatedly chosen Frere Hall as a suitable venue for protesting pertinent issues such as child abuse and lack of equal rights for women. On 8th March 2021, I attended the Aurat March in Frere Hall. The building was a mere backdrop to a diverse group of women, children, and men passionately chanting slogans advocating for women's rights.

The similarity of our demands made me feel connected to the women of my city: students, working and upper-class women, and elderly ladies dressed in vibrant traditional outfits, saris, lab coats and school uniforms. An intangible, deeply rooted connection permeated through the crowd, transcending social strata and ethnicity. A prevalent theme on posters that women carried was the right to safety in public spaces.

In addressing the query: "Where are the Women?" It is essential to recognise that the struggle for women's autonomy is influenced by a complex interplay of class, ethnicity, religion, and political factors, all of which are reflected in public spaces like Frere Hall.

This landmark serves as a symbol of women's experiences, displaying their active engagement with public avenues and resistance against prevailing societal norms. Despite the male-dominated environment, women persist in their efforts to explore and assert their identities within the urban landscape.

Farazin Zehra is a passionate writer from Karachi who likes delving into cultural stories that explore the intertwining narratives of heritage, architecture, and the dynamics of gender and identity in the city.

Header and thumbnail image by Geo.tv