Indian classical dance — An art form of defiance is catching up in Pakistan?

The future of classical dance in Pakistan hangs in the balance of the choices made by the young generation

By Maliha Khan

“Dancing is my way of resistance,” said Nazuk Rao, a Lahore-based writer who started learning semi-classical dance last year, from Fatima Amjed, a dedicated dancer and instructor in the cultural capital of Pakistan, seamlessly blending tradition with innovation in her teachings.

Classical dance, also known as Indian or Hindustani classical dance, is an umbrella term used for different types of regionally specific dance traditions in the Indian subcontinent such as Bharatanatyam, Kathak, Kuchipudi, Odissi, Kathakali, Sattriya, Manipuri, and Mohiniyattam. Each of these dance traditions originates and comes from a different part of India.

Bharatanatyam is from Tamil Nadu in the south of India, Odissi is from the east coast state of Odisha, and Manipuri is from the northeastern state of Manipur. One wonders how an art form, so rooted in the Indian culture and society, can be practised, even celebrated in the heartlands of Pakistan.

Dilemma of cultural identity

Talking to Big Picture, Sheema Kermani, a renowned classical dancer, social activist, and founder of the Tehrik-e-Niswan Cultural Action Group (Women's Movement) said soon after Partition, the Pakistani state fell into the dilemma of cultural identity.

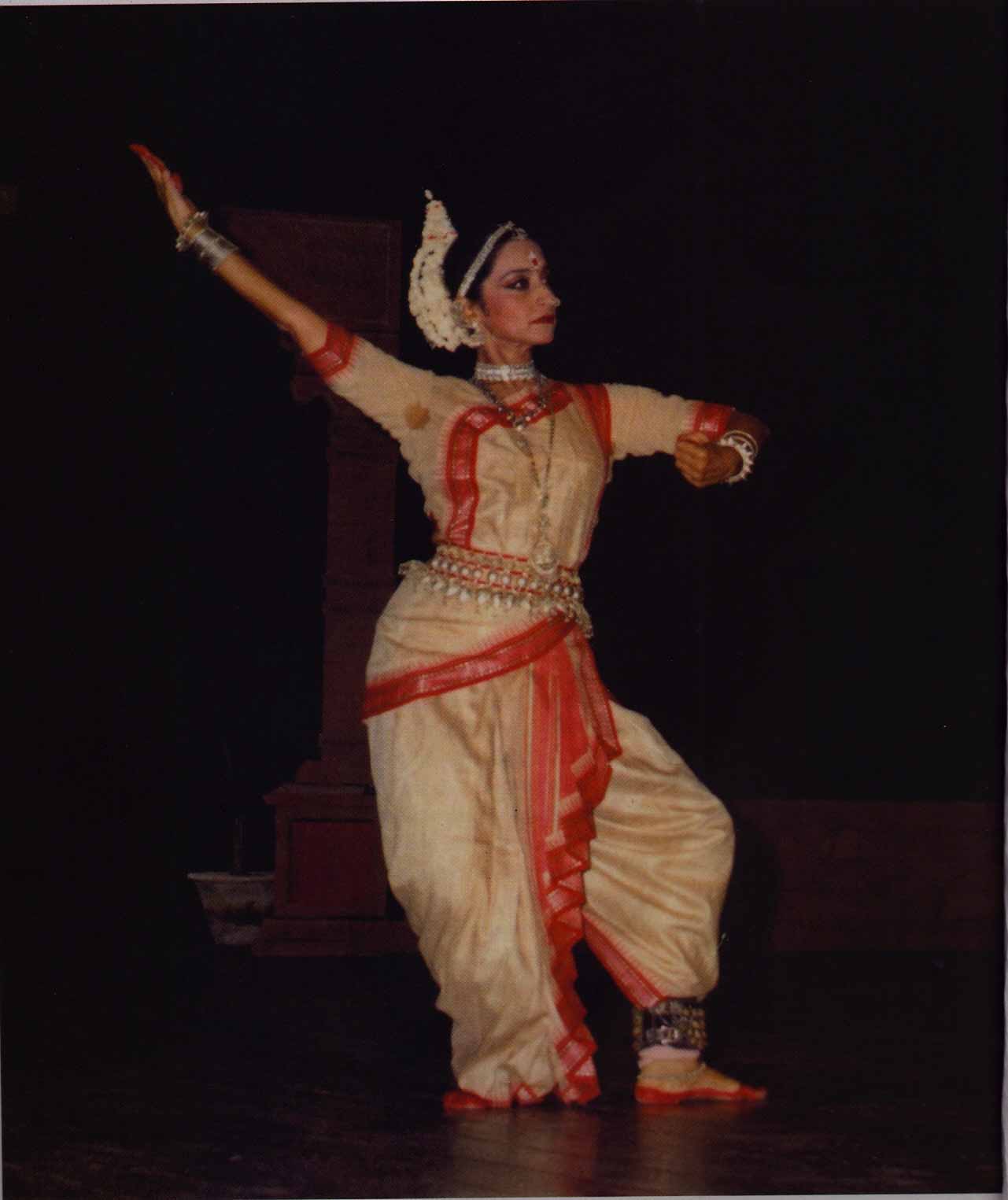

Dancing for the past 50 years and specialising in Odissi, Kermani is a renowned classical dancer, choreographer, dance guru, theatre practitioner, performer, director, producer, and television actor based in the largest city of Pakistan, Karachi.

“In its search for a cultural identity as apart from the cultural identity of India, Pakistan has looked upon the art of dancing with suspicion. It has continuously been claimed by the official authorities that dance is not part of Pakistani culture,” Kermani added when asked how art forms such as “Indian/Hindustani” classical music or dance were perceived in Pakistan after the partition of India in 1947 and the creation of the new Islamic state for the Muslims of the subcontinent.

'Resis-dance' during Zia regime

In 1981, Pakistan's military leader General Ziaul Haq-led regime cracked down on dancing as part of its push for stricter religious practices. This ban particularly targeted women who danced in traditional clothing wearing ghungroos, the ankle bells worn by classical dancers.

The new law not only forbade women from dancing in public but also disbanded the Arts Councils and the National Performing Arts Group. Even the PIA Arts Academy, which came into being in 1966 under the patronage of Pakistan International Airlines, was shut down and a dance programme named ‘Payal’ on Pakistan Television (PTV) was removed from the state television channel as well.

“For most part of our history we have had martial law governments and even the civilian governments’ cultural policies have had ‘concealed fascism’ in their behaviour,” Kermani said.

She added that a culture policy drafted by the National Commission on History and Culture stated: “A comprehensive history of Pakistani culture will be undertaken by the National Institute of Historical and Cultural Research, highlighting the indigenous culture of Pakistan as well as the impact of Arab, Iranian, Central Asian and Western cultures.”

Yet, despite several attempts to ban this art form in the past, dancing inadvertently became a symbol of resistance and defiance.

Bringing it to Gen Z

Recently, however, there seems to be a sudden resurgence in the interest in classical dancing amongst the young generation of Pakistan. “Semi-classical dance, a fusion of classical dance along with other contemporary forms is attracting young people and connecting with Gen Zs more,” Tabitha Simrin Bhatti, a young Kathak dancer in Karachi, said.

Social media seems to have played a significant role in promoting this art form, especially among young Pakistanis. Zehra Nawab, a movement actor, who has used classical dancing techniques to help with stage presence in her theatre career, felt that creative expression is innate to us. “Social media has only given people a platform to share their form of creation,” she told the Big Picture.

An art form, not just entertainment

Classical dancer Fatima made her Instagram account public last year after facing a lot of resistance from her family, she said, narrating her journey to an audience in her TedxLahore talk. However, that is not the only public space she wants her dancing to be limited to, or even in front of a specific audience. “I wanted to take my dance out of the theatres and take it to the streets,” she shared passionately in her speech.

Fatima shot a video of her dancing in the streets of old Lahore for a Pakistani clothing brand, which invited a lot of hate comments from men and women alike, saying that she was promoting the ‘tawaif (courtesan) culture’.

Historically, classical dance in the subcontinent was also a domain of the courtesans who catered to the nobility of the Indian subcontinent during the Mughal era. Known as the connoisseurs of the fine arts much like Japan’s geishas — a Japanese word for art person, their status and patronage began to deteriorate to mere prostitutes, after the advent of the British rule in India.

Suhaee Abro, a Pakistani actor and practitioner of Bharatanatyam classical dance, said she has had to constantly explain to people that dance is an art form, and not just about sexuality or something that happens in the red-light districts to entertain men.

Role of feminist movements

In the past few years, there has been a new wave of feminist movements in Pakistan, culminating in the Aurat March in 2018, an annual socio-political demonstration in the major cities of the country on March 8, International Women’s Day.

“Youngsters have definitely benefited from feminist movements,” Abro said, giving them the autonomy to take bolder decisions like pursuing such arts, despite the conservative mindsets of parents and families.

Young Pakistanis, especially women, are now becoming more aware of the choices they can make and are using their newfound sense of independence and freedom to push the boundaries they have been confined in traditionally.

“I feel free when I dance, it makes me feel empowered. It’s a connection between my mind and body and an exploration of my body for me through movements. Dance is also one of the tools I can use for activism. I want to use this art form to tell stories of the marginalised and oppressed communities.”

For others like Nazuk, it became about getting more in touch with her femininity. “There is a certain kind of delicate sensibility which I aspire towards that I find appealing in classical dance, which made me take it up.”

Dancing the lockdown away

In 2020, when a global pandemic forced everyone into months of lockdown, people had to somehow suddenly find ways to make sense of time.

“It gave us a chance to pause and take time out for things that brought us joy, especially in a time riddled with anxiety and stress for the unknown and a very deep pain of not knowing when you can see loved ones again,” said Zehra, who started learning Bharatanatyam from Suhaee through online Zoom classes during the lockdown.

“It also made everything become a lot more accessible. People realised that they don’t have to live in a certain city or country to take a class from a certain person,” Suhaee noted.

Instant culture, instant outreach

Bollywood and pop culture also seem to have contributed to this resurgence of interest in classical dancing. Viral songs such as Ali Sethi and Shae Gill’s Pasoori showcased Kermani dancing in a saree in its music video which seemed to have connected with a lot of young people who now know the seasoned dancer through it.

“My appearance in Pasoori certainly brought classical dance to many young people, and yes, I think it has also helped in creating an interest in classical dance. Ever since Pasoori has hit the charts I have had many students show interest,” Kermani said.

However, she added, no one is ready to spend months if not years to learn dance, in light of the culture developed in Pakistan. “Students think they can learn classical dance in a couple of weeks – like ‘instant’ coffee they think they can get ‘instant’ culture!”

With a general revival of interest in knowing about our history and culture nowadays in young people of a certain subset of society, especially through social media, it appears that more and more young Pakistanis are now engaging with our lesser-known traditions. However, not everyone shares that opinion. Zehra feels that artistic expression was celebrated earlier especially in my grandparents’ generation but yes there are certain questions that recent movements have led us to ask ourselves or challenge certain assumptions.

A dead art form?

Others such as Kermani, the oldest exponent of classical dance in Pakistan, have a more extreme view on this. “I do not see any burgeoning interest in classical dancing – in fact on the contrary I think that classical dance in Pakistan is now a dead art form.

"There is absolutely no institution that is keeping it alive. A couple of individuals who practice classical dance and continue to teach it to a sprinkling of students is all that I can see.”

True or not, but it's evident that the future of classical dance in Pakistan hangs in the balance of choices made by the generation of the time. And these choices will decide whether classical dance flourishes, surpassing boundaries of nationality, religion, and gender, and evolves into a contemporary art form that strikes a chord with our society.

Maliha Khan is a Karachi-based writer. She is a 2022 South Asia Speaks fellow and is currently working on her first book about her experience of living in India as a Pakistani. She posts on X @malihakhnwrites and Instagram @malihakhanwrites

Header and thumbnail illustration by Geo.tv